The scent of a woman — or a man

Human scents may contain information about gender

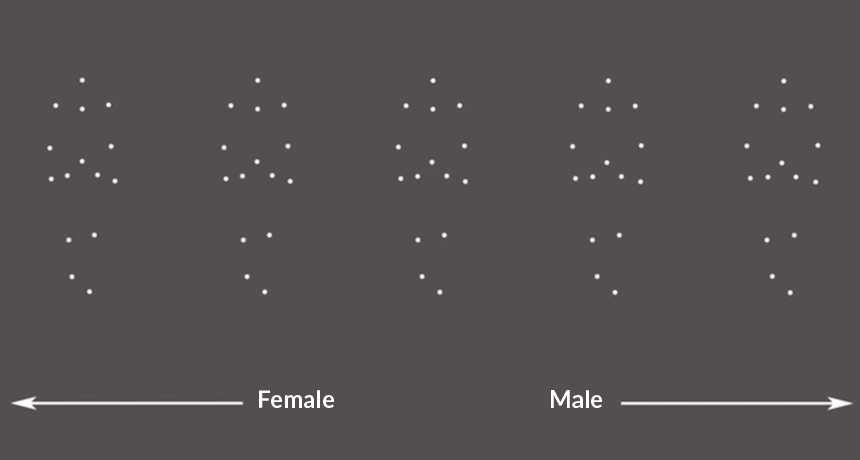

These patterns may look like random collections of dots, but to a person who's been sniffing certain chemical signals, they may look more masculine or feminine.

W. ZHOU ET AL/CURRENT BIOLOGY 2014

People learn about each other by looking and listening. But some information passes from person to person without either knowing it. That’s because the body can transmit signals through subtle scents. In a new study, scientists suggest that people attracted to men can pick up a manly scent coming off of guys. Similarly, a sniff may give away a woman’s gender — but only to people attracted to women.

The study suggests the human body produces chemical signals, called pheromones. And these scents affect how one person perceives another. Scientists have demonstrated the effects of pheromones in a whole range of animals, including insects, rodents, squid and reptiles. But whether people make them has been less clear.

The new study’s findings “argue for the existence of human sex pheromones,” Wen Zhou told Science News. An olfaction researcher at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, she studies the body’s ability to detect smells.

Zhou says people emit chemicals similar to those given off by animals. For example: When a female pig sniffs a chemical found in the saliva of male pig, she gets ready to mate. Men produce a similar chemical to that in their armpit sweat and hair. It’s called androstadienone (AN-dro-STAY-dee-eh-noan). Other scientists have shown that when women smell this compound, their hearts beat faster and their mood improves.

In much the same way, a chemical in women’s urine — estratetraenol (ES-trah-TEH-trah-noll) — lifts a man’s mood.

To explore the human impacts of these two chemicals, Zhou and her colleagues recruited 48 men and 48 women to take part in tests. Half of these recruits were attracted to people of their own gender or to both men and women. The scientists had all of their volunteers watch a video showing 15 dots moving around on a computer screen. At the same time, each recruit inhaled a concentrated form of one of the two chemicals. They weren’t aware of this, however. Each compound had first been cloaked with the scent of cloves, a strong spice.

The dots moving across the computer screen didn’t look like people. However, the way they moved reminded the study participants of people walking. And men who took a whiff of a female’s scent while watching the dots were more likely to rate those dots as looking feminine — but only if those men were attracted to women. Women had the opposite reaction. Those attracted to men said the dots looked masculine after a whiff of the male scent. The response of gay men was similar to that of heterosexual women: While inhaling a male scent, they thought the dots looked masculine. And women who were attracted to other women thought the dots looked feminine while inhaling a female’s scent. Zhou and her colleagues published their findings May 1 in Current Biology.

The brain recognizes gender in the scents that people give off, even when we are unaware of it, Zhou says.

But not every researcher is convinced the study settles the question of human pheromones. One doubter is Richard Doty. He directs the Smell and Taste Center at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

“The notion of human pheromones is fraught with problems,” he told Science News. For example, hesays, the new study may not reflect the real world. The human body may excrete these compounds at such low levels that the nose won’t detect them. If true, he says, the chemicals might not drive a person’s perception as strongly as the new test suggests.

Power Words

feminine Of or relating to women.

gay (in biology) A term relating to homosexuals — people who are sexually attracted to members of their own sex.

heterosexual A term for someone attracted to people of the opposite gender.

masculine Of or relating to men.

olfaction The sense of smell.

pheromone A molecule or specific mix of molecules that makes other members of the same species change their behavior or development. Pheromones drift through the air and send messages to other animals, saying such things as “danger” or “I’m looking for a mate.”