How to make ‘worms’ more nutritious — and easier to swallow

Scientists find better ways to extract protein and nutrients from insect larvae

Insects are an eco-friendly source of protein, but many people find the idea of eating them gross. By extracting their protein to make supplements, such as powders, manufacturers could camouflage their use in many cooked and baked foods.

ARISA THEPBANCHORNCHAI/iStock/Getty Images Plus

By Laura Allen

Mealworms for lunch? Ewww! For many of us, that would be our first reaction to finding these beetle larvae on today’s menu. But if we’re not so quick to “ick,” the protein from these insects has a lot to offer, say some researchers. That’s what’s behind new work to see how insect protein might be used to fortify many types of foods.

Edible insects are a healthy and sustainable source of animal protein. That’s why food scientists have been working to extract it — then turn it into a powder. That means diners don’t have to bite into any heads, legs or wormy bodies. But some extraction methods can degrade certain health benefits of that protein.

The new work seeks to prevent that. If it succeeds, it could open up new prospects for insect-based foods.

We need protein in our diets. That can come from sources such as beans, tofu, eggs or meat. Meat is high in protein. But some insect proteins may be healthier for us than the meat of larger animals, such as beef, fish or chicken. Farming insects is also better for the planet than other types of livestock. It uses less land, water and energy. And it produces fewer greenhouse gases, such as methane.

Overall, “insects have shown great potential,” says Yookyung Kim. She’s a food scientist at Korea University in Seoul. Kim values insects’ high protein content.

But there’s more. Many edible insects are full of vitamins and minerals. They also contain other compounds, such as amino acids and peptides, that can promote good health. In fact, some of these compounds are being studied to treat ailments such as cancer and heart disease. Extracting them from insects might lead to new health supplements.

From yuck to yum

To get there, science will have to pass a few hurdles. First is chitin (KY-tehn). It makes up the crunchy exoskeleton on many arthropods, from insects and arachnids to shellfish. Insect larvae contain some chitin, too. This sugar-based polymer binds to proteins and makes them hard to digest. So diners who eat whole insects won’t get full nutritional benefit from their proteins.

Treatment can separate out that chitin. Now, people can better absorb the protein.

But there’s still the yuck factor. Eating insects is normal in some parts of the world. Many of us don’t want to eat insects, however — no matter how nutritious they may be. And it’s hard to ignore that you’re eating insects if you crunch on their legs or wings. That’s a big reason why Kim focuses on turning the beneficial parts into a powder.

Plus, she adds, powders are practical. They tend to last longer than whole insects and are easier to ship.

But techniques to remove proteins can have their own problems, Kim’s team has found. Most take a lot of time, money and energy. This can make it hard for a small farmer to turn insects into powder.

Kim’s team decided to see if simpler, less costly methods worked. And they applied them to mealworms.

Powder power

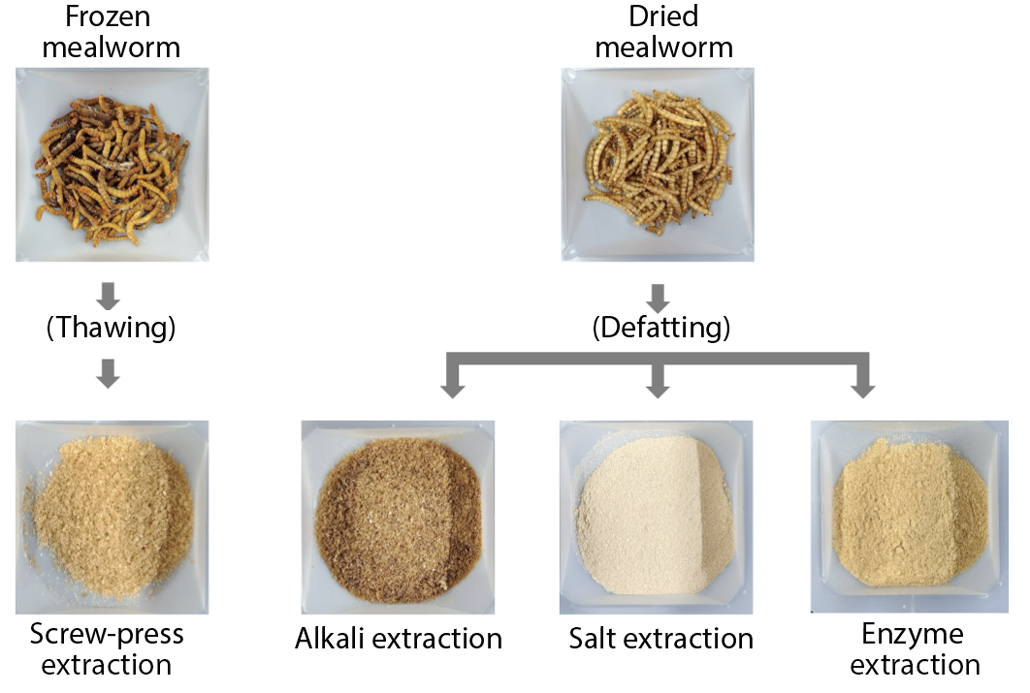

Despite their name, mealworms are larvae of the darkling beetle. Kim’s team tried four ways to turn proteins from these beetle larvae into powder. Then they tested how nutritional each powder was.

Three techniques started by drying the larvae, then grinding them in a blender. Next, the researchers soaked the ground worms in ethanol, a type of alcohol, to break up the fats. Then, they mixed in one of three solutions to dissolve the proteins out of the defatted worms. One solution was sodium hydroxide (NaOH). Another contained a salt. The third contained enzymes. Lastly, they freeze-dried the mix to remove water. The leftover material was crushed into a powder.

The fourth method was simpler. The team froze and then thawed the mealworms. Afterward, they ran the larvae through a screw press, which squished their tissue. This squeezed out any liquids. It’s similar to how olive oil is extracted from whole olives. Next, the team strained the liquid and freeze-dried it (to remove water). They powdered what was left.

The team analyzed how much protein, fat, amino acids and chitin were in each of these four powders.

Each powder had different advantages.

Powder from the screw-press technique, for instance, kept less protein but more of the fatty lipids. (Many lipids are healthful compounds that can help fight some diseases.) Other methods preserved more protein but lost some other nutrients.

So different methods — or a mix of them — might be chosen to preserve more of certain target ingredients.

The team shared its findings August 21 in the Journal of Food Science.

From protein powder to your plate

Catriona Lakemond is a food scientist at Wageningen University in the Netherlands. She, too, works on insect proteins for human diners. And she finds the new data interesting. People are more likely to accept eating a powder rather than a whole insect, she says. Plus, she adds, extraction allows for the protein to find a wider range of uses.

Still, there remain challenges to getting these insect powders onto dinner plates, Lakemond says.

It’s not yet easy to find this protein — or foods made with it — at the grocery store. Lakemond wants it to be easier for farmers to grow, process and sell edible insects. And more people will need to be ready to buy foods made with insect ingredients.

Food allergies are another factor, says food scientist Andrea Liceaga. People with shellfish allergies, she notes, may also be allergic to insects.

Liceaga works with insect proteins at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Ind. Her past work has shown that how protein is extracted can affect how likely it is to trigger an allergic reaction. So it will be critical to test insect-based products for allergens, she says.

The future of edible insects

All these food scientists imagine us one day eating more insects. Which type and how they’re prepared will probably depend on people’s culture, says Liceaga. But at some point, insects will become just another ingredient.

And what seems gross today might soon become desirable. By way of example, she points to lobster. Today it’s a pricy delicacy. But in colonial America, it was an unpopular “poor-man’s food.”

No matter how healthy or planet-friendly insects may be, Lakemond says, one thing is key for people to eat them. “We need to make really good products with a good taste.”