The moon has new tales to share, some from its secretive far side

Observations and new rock samples point to how it — and our Earth — evolved

The moon has been Earth’s constant companion for billions of years. Scientists are hard at work studying its familiar near side — and recently, its mysterious far side — to better understand both how this orb formed and how Earth has evolved over the eons.

janiecbros/Creatas Video/Getty Images Plus

The moon is Earth’s longtime companion. A bright full moon can light a path through the dark of night. It’s long been important for navigation and marking the passage of time. Many civilizations and cultures have used lunar calendars. The dates of some holidays are even set based on the moon’s cycle. Visible from everywhere on Earth, the moon has inspired countless bedtime stories, poems, paintings and other forms of art.

“It’s one of the few things that unites everybody on this planet,” says Noah Petro. A planetary scientist, he works at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.

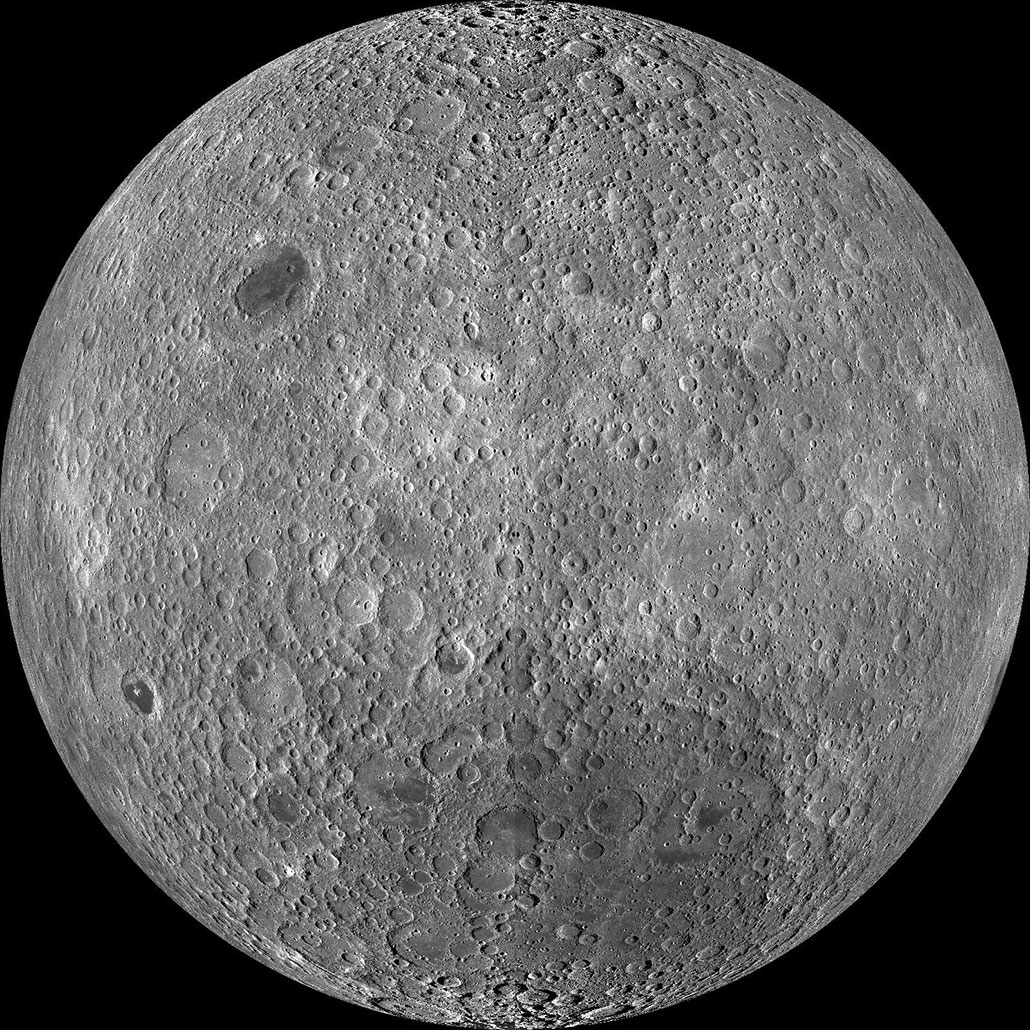

But we Earthlings only ever see half of the moon. Earth’s gravity locks our celestial companion in such a way that the same side always faces us. The other half — the so-called far side — looks different. And scientists have only just begun to learn what it’s like.

Over the past half century, scientists have studied hundreds of pounds of lunar chunks. Almost all were retrieved from the moon’s near side. In June, though, a Chinese spacecraft brought back rocks and soil from the far side.

They represent the first hands-on exploration of our companion’s unseen side — and will soon reveal how different the near and far sides are.

Those pieces can also help put together a timeline of the moon’s evolution. Its stories, in turn, can tell us about the events that shaped our own planet, says Yuqi Qian. He’s a planetary scientist at the University of Hong Kong, in China.

Indeed, he explains, “I study the moon because the moon can tell you about the Earth.”

How the moon formed

In the beginning, our solar system was just a disk of gas and dust orbiting a baby sun.

By some 4.5 billion years ago, that gas and dust had begun to glom together. This formed larger pieces. For millions of years, the resulting space rocks smashed, merged and grew. The young solar system was like a cosmic game of dodgeball.

Then, “over time, the impacts become less and less,” says Miki Nakajima. Why? These pebble-formed planets, she notes, had already eaten up the neighboring rocks. Nakajima works at the University of Rochester in New York, where she studies how planets form.

At some point during these cosmic collisions, a protoplanet likely slammed into the young, developing Earth. Such a smash would have been powerful enough to break apart the colliding orb. It also may have knocked loose some matter from the young Earth and sent it into space. All that floating debris could have mixed before glomming back together.

Most scientists agree such an impact happened. Details of what happened next are less clear.

Studies show that certain types of chemical elements in moon rocks match those on Earth. To Nakajima and others, this suggests Earth and its moon come from the same source. Whatever formed the moon left its mark on Earth.

Perhaps the impact spewed material from the young Earth into space, where the debris mixed with the colliding object and formed the moon. Or maybe the energy from that smashup vaporized both the impactor and the top layers of Earth into small particles. These might then have mixed in space, some material becoming our moon and the rest falling back to Earth’s surface.

Some of the mixed debris may still be stuck below Earth’s surface, according to a November 2023 study in Nature. Seismic images show blobs of material under the Atlantic Ocean that could be leftovers of that protoplanet.

By about 3.8 billion years ago, things settled down. Since then, our solar system has looked much as it does today, with eight major planets orbiting the sun.

One of them is Earth and its natural satellite.

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores

History, recorded

The moon has been right by Earth’s side since it formed. That means what happened to the early Earth also happened to the moon. Each faced similar rates of hits from space rocks. Each was bombarded by the same number of flares and other energetic events from the sun.

Over time, though, Earth’s surface has changed a lot. On our planet, continents have shifted and morphed over millions of years (see slideshow here). Erupting volcanoes oozed rock-forming lava. Rain and rivers carved canyons and washed away layers of rock.

Those changes “here on Earth that make it really great to live [on],” says Kelsey Young, are “not so great for the rock record.” She’s a planetary scientist at the Goddard Space Flight Center. Newer changes erase or overwrite past details.

Lucky for us, the moon has recorded much of that lost history. So by understanding the lunar surface — through stories told by moon rocks — scientists can learn more about Earth’s history. They also can learn about the early solar system. Piecing it together, explains Petro, her Goddard colleague, is “kind of like detective work.”

Marked by collisions and volcanism

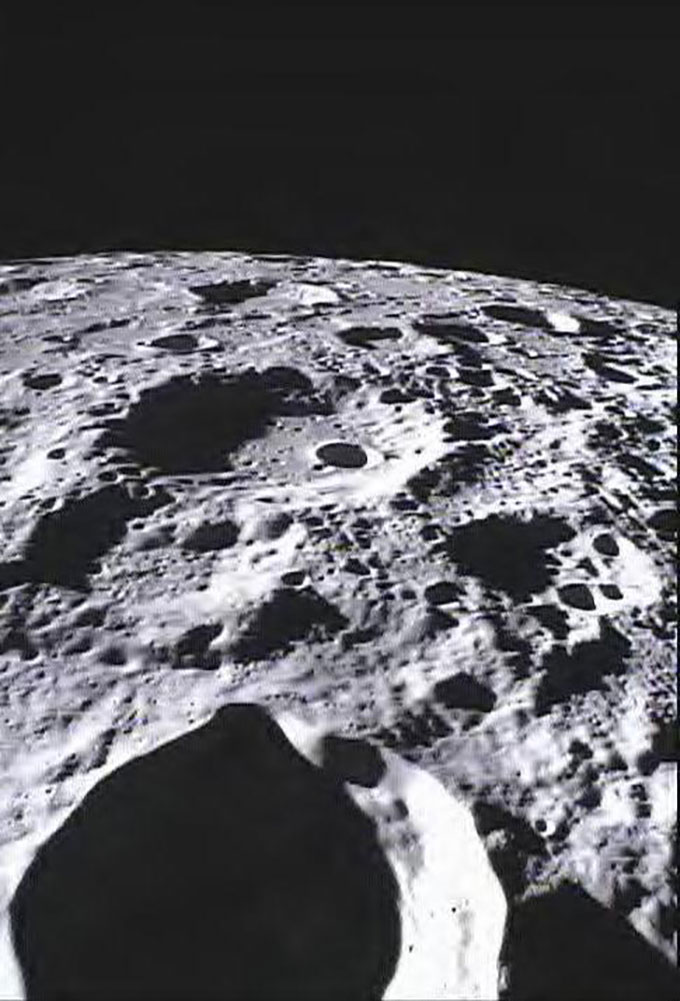

Pockmarking the gray lunar surface are millions of craters and basins. Scientists have cataloged ones that range from a few meters (yards) across to 2,500 kilometers (1,550 miles) wide. Most of the rocks that made those craters likely slammed into the moon during that giant game of cosmic dodgeball more than 3.8 billion years ago. The newest craters are layered on top of older ones.

Dark patches also cover the side of the moon locked toward Earth. Scientists think the dark basins mark ancient lava eruptions. Molten rock once oozed through surface cracks made by incoming space rocks. Later, that lava solidified. That rock, like volcanic rock here on Earth, is basalt. It appears a very dark gray.

The far side, though, looks “very different,” says Qian. It’s a lighter gray color with fewer giant dark patches of lava. He’s among scientists working to understand why the hemispheres look so different.

One idea, he says, relates to a time shortly after the moon formed. He and many other scientists think the young moon’s surface was still liquid rock — an ocean of magma. Maybe the far side crystallized, or became solid, before the near side, he says. If it did, the crust might also be thicker there.

Later, he says, magma might not have been able to reach the surface and ooze through as easily as on the near side.

To test this idea and others, scientists would need to run experiments on materials up close. But everything that astronauts and robotic rovers have collected had come from just the moon’s near side — until this past summer.

Sampling the moon

On June 25, the Chinese spacecraft Chang’e-6 returned to Earth with a treasure — 1,935.3 grams (almost 4.3 pounds) of moon rocks and soil. What made this loot extra special was its source: a never-before explored part of the moon.

Chang’e-6 had spent a few days in the Apollo basin on the moon’s far side. That site is near the inner edge of the enormous South Pole-Aitken Basin. At about 2,500 kilometers (1,550 miles) across, that’s the biggest impact crater on the moon. It spans almost one-quarter of the moon.

Scientists have mapped other craters layered atop South Pole-Aitken Basin. Based on these, it appears to have formed about 4.2 billion years ago. That would make it one of the moon’s oldest features. “That basin is special,” notes Qian, precisely “because it’s ancient.”

In fact, this crater helps scientists know when the solar system’s dodgeball game started. The samples Chang’e-6 brought back may tell scientists something about that timing and the impact-rich years that followed. By studying these pieces up close in the lab, they can start to measure ages of the rocks.

Qian and his coworkers have only just started. “It’s ongoing research,” he says.

Soon, however, we will learn what those rocks have to say.

Magma and the moon

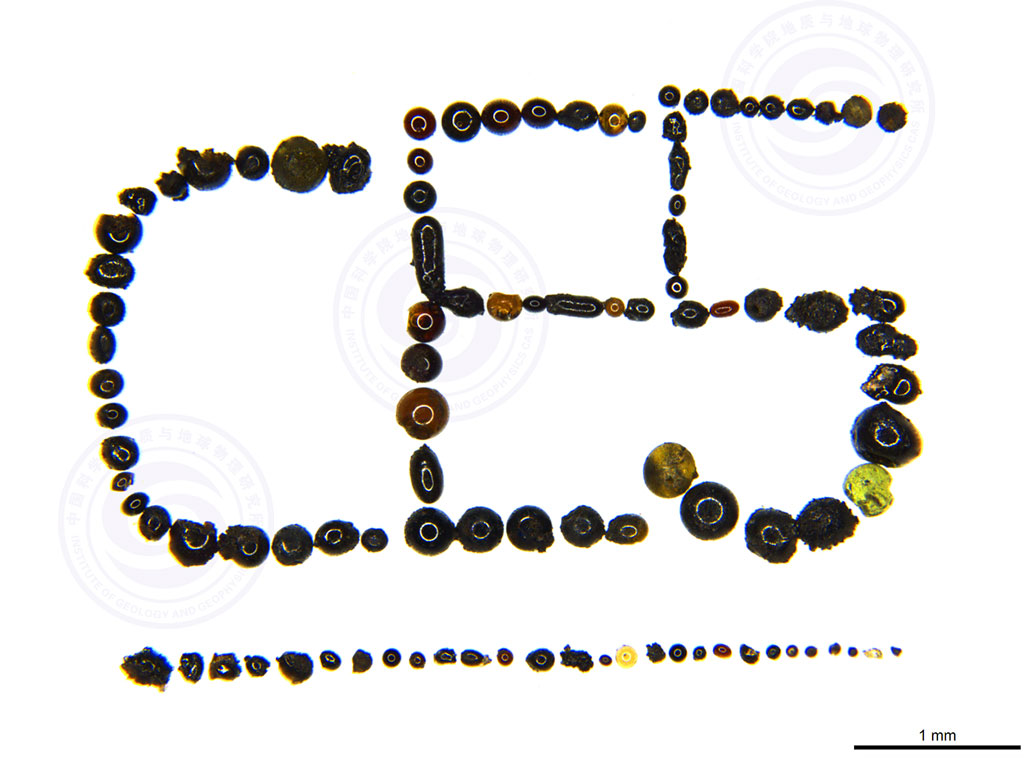

These samples — plus another soil-and-rock haul and observations from other spacecraft in the past few years — are also helping point to how the moon evolved.

Scientists have been comparing Chang’e-6’s newly collected rocks to soil and other rocks collected through previous missions. Those include older samples from the 1960s and 1970s that were picked up as part of NASA’s Apollo program and robotic missions by the Soviet Union.

They also include samples collected in 2020 by another Chinese spacecraft, Chang’e-5. That mission brought back rocks and soil from a large lava-filled basin on the moon’s near side.

Before looking at those samples, researchers had doubted the moon had liquid magma more recently than about 3 billion years ago. They thought the lunar interior would have been too cold for any hot magma to ooze out. But the moon appears to have been active far more recently — just over a hundred million years ago.

That’s based on a September report on Chang’e-5’s samples. Li Qiuli, a geochemist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing, and his team led that study. The chemistry of a few glass beads in those samples points to magma flowing possibly just 120 million years ago. Though that may sound ancient, it is very recent for astronomical objects.

A mission from India returned even more clues about the once-volcanic near side. The Chandrayaan-3 mission landed near the south polar region in 2023. This mission, too, turned up data on the age of lunar magma. Astrophysicist Santosh V. Vadawale led the team that described those findings August 21 in Nature. He works at India’s Physical Research Laboratory in Ahmedabad. His team’s data suggest the moon may once have hosted a giant liquid-magma ocean.

For billions of years, the force of gravity has bound our moon and planet together. No surprise, then, that our moon is the most explored world after Earth. Dozens of spacecraft have either orbited or landed on it. Twelve astronauts have walked upon it as part of six different missions.

Yet there’s still so much to learn. Moon rocks carried back to our world are a library of yet unexplored data, says Petro. Think of them, he says, as “little books. They tell us the history [of our moon].”

And imagine what wonderful new tales await in the volumes that Chang’e-6 has just brought back from the moon’s far side.