Are plants intelligent? It seems to depend on how you define it

Plants communicate, learn, even remember — and that’s fueling a big debate in biology

Some plants — like the poplar trees bordering this wheat field — can communicate with each other by sending messages through the air.

Alan Majchrowicz/Stone/Getty Images Plus

It’s a pleasant summer morning. Across a field, a line of poplar trees sways in the breeze. Insects buzz and flit among the branches. Everything seems calm and peaceful.

But don’t be fooled. These trees are actually under attack as hungry insects chomp on their leaves.

The trees can’t hide, and they can’t run away. But they aren’t helpless: They have ways to fight back — and even aid each other. As soon as an insect starts gnawing on a leaf, the tree mounts defenses. It also quickly messages its neighbors: “We’re under attack! Get your defenses ready!” It might even call on other insects for help.

Educators and Parents, Sign Up for The Cheat Sheet

Weekly updates to help you use Science News Explores in the learning environment

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

All of this happens in ways we don’t see. But scientists are learning that plants can do many things we associate with thinking. Plants communicate with each other. They can learn. They form memories. They can even recognize their relatives. And they do all this without a brain.

Could these abilities mean plants are intelligent? We may never fully know. As Simon Gilroy puts it, “It’s very difficult to think like a vegetable.” Still, researchers are working to get to the root of what’s going on when plants act in ways we once thought only animals could.

Talking seedlings and frightened mimosas

“When you look at a tree,” says Gilroy, “it looks like it’s doing absolutely nothing.” Gilroy is a botanist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. He’s also one of several scientists who’ve been taking a close look at plant behavior. They’re finding that though plants seem still and quiet, they’re actually quite busy.

And what they’re busy doing is pretty amazing.

In the 1980s, botanists first found signs that plants communicate with each other. In one early experiment, hurt trees seemed to warn their neighbors of danger.

Back then, Jack Schultz and Ian Baldwin were young researchers at Dartmouth College in Hanover, N.H. They potted up tree seedlings and sealed them inside a clear plastic container. Each had its own pot, and the trees didn’t touch each other.

When the researchers tore leaves on one tree, it responded by producing a chemical to repel attackers. Then, about 36 hours later, the undamaged trees made the same chemical. The hurt tree must have sent a signal through the air to the others, the team concluded.

Some people described this as plants “talking” to each other. The finding, reported in 1983, launched the science of plant communication.

Since then, scientists have shown this communication can be fairly complex.

Plants respond better to messages from close kin than to ones from unrelated plants. It’s something Rick Karban has shown. At the University of California, Davis, he studies how plants and insects interact. Work by his group and others shows plants can tell one predator from another. They send different signals depending on what type of insect is attacking.

Their messages can even signal how far away danger is, a team in Finland now reports. It shared that finding September 12 in Science.

And not all plant messages are intended for other plants. Some are meant to lure in critters that eat whatever’s feeding on the plants. When nibbled by tomato hornworms, for instance, tomato plants release chemicals that attract the hornworm’s enemies, explains Schultz. He now works at the University of Houston in Texas.

Plants can even use more than one “language.” Most studies have focused on chemical signals. But plants sometimes use sound, too.

In 2023, a team in Tel Aviv, Israel, recorded clicks and pops made by plants under stress. The sounds varied across plant species and type of stress, such as drought and being cut. Although roughly as loud as human speech, they’re too high-pitched for people to hear. Other animals, however, such as bats, mice and insects, might be able to hear them, the researchers note.

Plant pops

Stressed tomato plants make distinctive clicking noises that can be picked up by ultrasonic microphones. In this clip, scientists condensed the sounds and brought them into the range of human hearing.

So might other plants. There’s lot of evidence that plants respond to sounds, says Heidi Appel. She’s a plant ecologist at the University of Houston. For instance, plants can hear when insects munch on their leaves, her team has shown.

Other work suggests that plants can learn and even remember. One famous study in 2014 used a plant called Mimosa pudica. Known for being “sensitive,” it curls its leaves when it’s disturbed.

The researchers potted up dozens of these plants. Then they dropped each Mimosa 60 times in a row. The plants weren’t harmed by the drop. It was short, with a soft landing. And they curled their leaves — but only the first few times. Pretty quickly, they stopped reacting.

Just to be sure the plants weren’t too tired to fold their leaves, the researchers shook the plants. Now they curled their leaves right away. But when dropped again, they didn’t curl them. The plants had learned that the drop wasn’t going to hurt them, the researchers concluded.

A month later, they tried the experiment again. The plants still didn’t curl their leaves after being dropped. It was as though they remembered it wouldn’t hurt them. They had formed long-lasting memories.

No nerve cells, no problem

It shouldn’t be surprising that plants can do all these things, Gilroy says.

“Everything that’s alive has to solve the same problems,” he notes. “Plants have to feed themselves. Plants have to get water. Plants have to defend themselves.”

But plants solve these problems very differently than animals do. A hungry person might chase down a deer or search out fruits. A plant’s food comes from sunlight, carbon in the air and nutrients in the soil.

And a plant can’t swat or avoid insects, as we might. Instead, they’ve evolved their own ways to solve problems. Plants turn to follow the light. They deter bugs by making bitter compounds. They send roots toward water and nutrients. They even release chemicals that change the soil to make it better for the plant, says Gilroy.

None of this involves a brain or nervous system.

How do plants remember and send messages without a nervous system? The researchers who dropped the mimosa plants had an idea about that. They suggested that there may be other ways to remember.

Neurons, or nerve cells, send messages via chemicals called neurotransmitters. Even though plants don’t have a nervous system, they have many of the same neurotransmitters that animals have.

One of those is glutamate. Wounded leaves use glutamate to send messages. These signals tell undamaged leaves to boost their defenses against possible threats, notes Edward Farmer. A plant biologist at the University of Lausanne in Switzerland, he and his team published this finding back in 2013.

Since then, other teams have learned more about how this messaging works. And it’s very similar to how neural signaling works in animals — but maybe better, Gilroy and his team show.

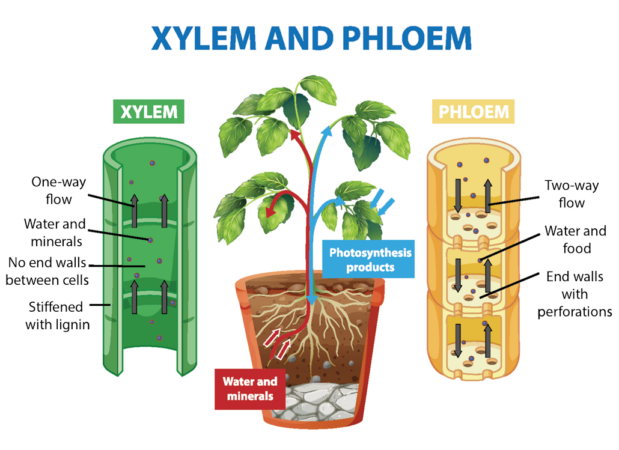

Plants have what Gilroy calls a plumbing system. This system of tubes, called xylem and phloem, moves water and nutrients around the plant’s body. Plants use this plumbing like a nervous system, he says. Neurotransmitters can move around their bodies through these tubes. No nerve cells needed.

“Plants have to do it better than human beings,” says Gilroy. They can’t run away when something bad is happening. They have to know exactly what’s going on and how to respond. “So the information processing must be really sophisticated,” he says. “It’s just not like ours.”

Does this mean plants are intelligent?

These discoveries show plants are able to do far more than meets our eyes. But does this mean that plants are intelligent? Some scientists think so. Others are not so sure. The problem may trace to how we define words like “thinking” and “intelligence.” Still, this has become a big controversy among botanists.

Elizabeth Van Volkenburgh is a plant biologist at the University of Washington. That’s in Seattle. She’s a founding member of The Society of Plant Signaling and Behavior. It had once been called the Society for Plant Neurobiology. But some scientists thought the term “neurobiology” was a poor fit. After all, plants don’t have nervous systems.

Some scientists are “very, very, very [against] the idea of plant neurobiology,” she says. But Van Volkenburgh likes the term. Technically, a plant lacks nerves. Still, it has a sensory system. What’s more, she points out, “In the older scientific literature, xylem and phloem were referred to as nerves.”

The idea that plants can hear was a hard sell 10 years ago, Appel recalls. She’s married to Jack Schultz, and even he was skeptical. ”And he’s the one who discovered talking plants,” she says, laughing.

Even now, this idea raises questions.

“We do know that plants respond to vibrations in their environment. There’s no debate about that,” Appel says. However, whether plants can “hear” seems to depend on what you mean by that term. “If you define hearing as detecting vibrations in the environment, recognizing different kinds of vibrations and responding in an appropriate way,” she says, “then yes, plants can hear.” That doesn’t mean plants think about what they hear in the same way we would, though.

And as to whether plants are intelligent in the way we think of human intelligence, Appel says we just don’t know. “These are mysteries we’re trying to understand.” Still, she argues, we need to resolve this controversy. And that means doing more science.

Or maybe it’s not a question we have to answer, counters Karban at Davis. “Many people in this field are upset and don’t like the word ‘intelligence.’ I couldn’t care less,” he says. “A lot of it is just about words.”

Words can be hard to define, agrees Andre Kessler. He’s a chemical ecologist at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y. In a paper that came out last April, he addressed what he calls the “plant intelligence hypothesis.”

It’s hard to agree on whether plants are intelligent without first agreeing on what intelligence is, he says. He and Michael Mueller point to one paper that found more than 70 different definitions for intelligence. It would be better, they write, to focus on what plants can do. How do they interact with other organisms, for instance? How do they respond and adapt to their environments? By such measures, Kessler says, plants should be viewed, in some way, as intelligent.

However you describe it, scientists are learning that plants are far more amazing than most people realize. And to amaze us, they don’t have to be like us.

Take a look at the plant on your windowsill or a tree in your garden. It won’t ever be able to pass your math exam. Even if you whisper to it every day, it won’t learn your name. But when it comes to doing what it needs to do — the things that matter to it as a plant — it’s remarkable. And it does all that without a nervous system.

Concludes Schultz at Houston, “You don’t need a brain to be an elegant solution to life on Earth.”