50 years on, Lucy offers lessons for achieving fossil fame

Discovered in 1974, her skeleton kicked off a new way of thinking about human evolution

The ancient hominid known as Lucy (reconstruction shown) is familiar all around the world.

© Sculpture Elisabeth Daynes/Photograph Elisabeth Daynes

By Bruce Bower

One of the biggest superstars in human history lies in the National Museum of Ethiopia. Here, in Addis Ababa, sit the fragile remains of the world’s most celebrated human ancestor: Lucy. Once, she was a hardy survivor in a harsh landscape. Now, her partial skeleton gets round-the-clock protection in a specially constructed safe.

Nearly 3.2 million years ago, this ancient female roamed East Africa’s landscape. She was not large, standing a bit over 1 meter (3 feet) tall and weighing no more than about 30 kilograms (66 pounds).

But she has had a huge impact on the story of human evolution. Today, half a century after her partial skeleton was found, people everywhere know Lucy.

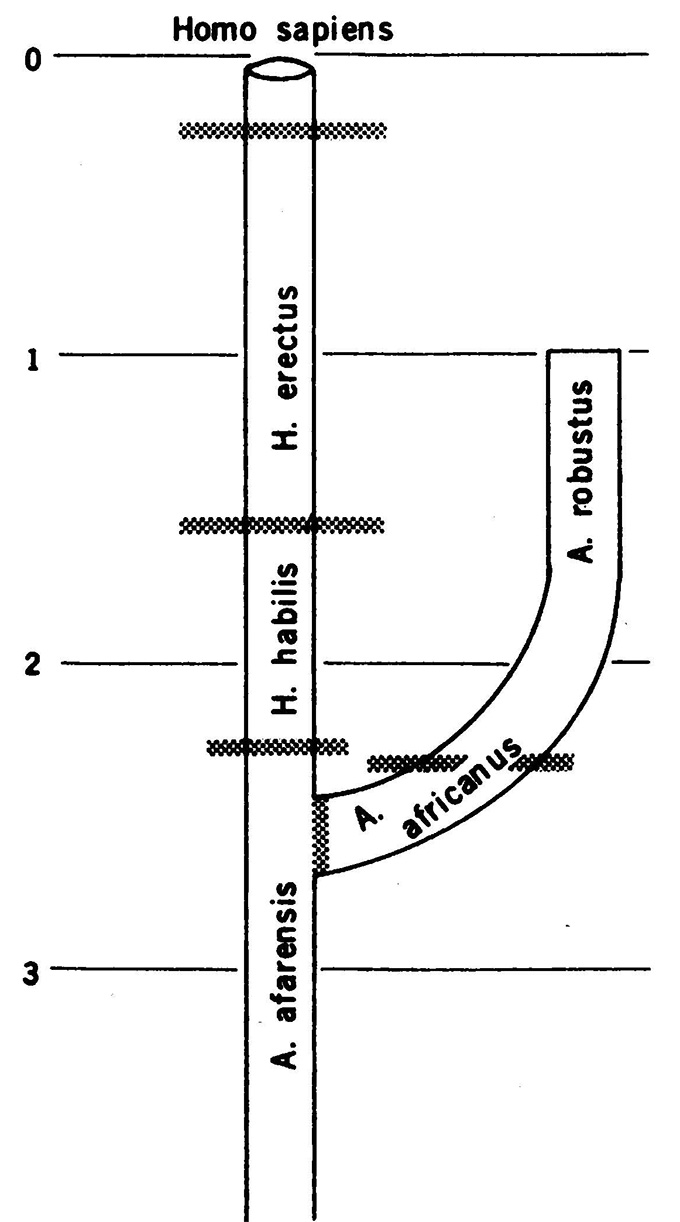

Her discovery in 1974 ushered in a new way of thinking about human evolution. Many paleoanthropologists at the time viewed the process as a straight line. One ancient Homo species led directly to the next until the emergence of present-day people, they thought.

But Lucy’s appearance muddied this idea. Some of her features were very humanlike. This included her curved spine. Other traits were apelike, including long arms and a brain no larger than a chimp’s.

Together, these traits pointed to a more treelike picture of human evolution. In that scheme, multiple species branched off in different directions. Some died out completely. Others led to the Homo genus — and, eventually, to us.

Lucy’s mix of features also sparked many new questions. How did two-legged walking emerge? When did humans’ large brains evolve?

Importantly, Lucy’s discovery kicked off a series of fossil finds. Together, they filled in the scientific picture of her species. By 1978, Lucy was declared the founding member of a new species. It was named Australopithecus afarensis (Aw-STRAAL-oh-PITH-ih kus AF-er-EN-sis).

The last 50 years have turned up many other fossils from human ancestors. (Collectively, such ancestors are known as hominids or, more often, hominins.) But none have come close to Lucy in name recognition. A look back at her story reveals tips for how to rise to fossil fame.

Get buried — but not too deep

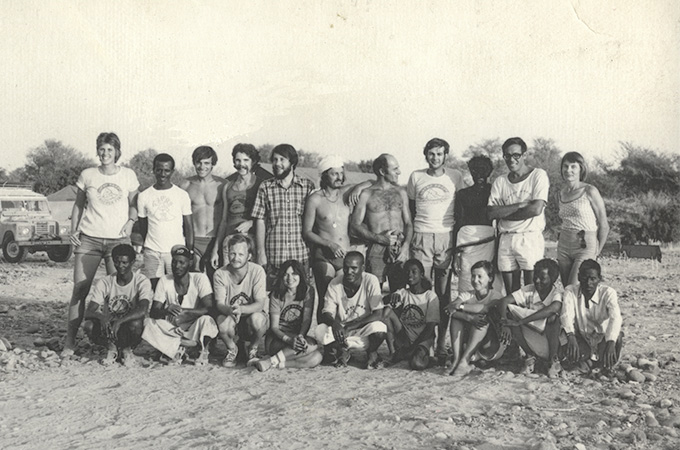

In 1974, Donald Johanson and Tom Gray were on a fossil hunt in a remote part of Ethiopia. Johanson was an American paleoanthropologist. Gray was a graduate student who worked with him. On the morning of November 24, they were mapping and surveying promising spots.

They walked through a gully at a site known as Hadar. Then Johanson noticed a forearm bone sticking out of the ground. A closer look confirmed that the bone came from a hominid.

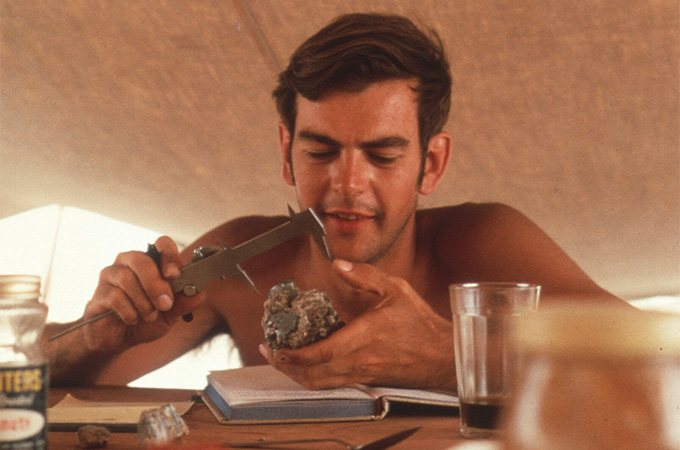

The pair gingerly dug out many more pieces of bone from loose soil nearby. After two more weeks, the researchers and their colleagues had uncovered several hundred bone fragments. It was a big haul. Often, just one ancient skullcap or partial jaw can require weeks or months of careful excavation.

From those finds, the team pieced together 47 bones. They formed a small fossil skeleton about 40 percent complete. It was the most complete early hominid skeleton at that time — by a lot.

Geology had worked in Johanson and Gray’s favor. Lucy’s remains were not found where she died. Flooding had carried away her body, probably shortly after death. It washed into a sandy channel. A quickly forming lake would have buried the body.

The moist sediment kept her bones in relatively good shape. And the fossils were pretty close to the surface. So later, once the lake had dried up, the bones began to emerge from the sandy ground — just enough to get the fossil party started.

Hang out with the right (fossil) crowd

This same land yielded many other hominid fossils from 1973 to 1977. Several would turn out to belong to the same species. This confirmed Lucy was part of a larger A. afarensis population.

Other fossil finds helped scientists distinguish between two related species. Lucy’s East African species was one. The other was Australopithecus africanus, previously identified in South Africa.

Over time, fossils from several East African sites have been determined to be A. afarensis. Hadar has yielded about 90 percent of the nearly 600 fossils so far attributed to this species.

Hadar’s geology also gave Lucy a big advantage in the ancient dating game. Radioactive dating, that is. Three Hadar sediment formations hold A. afarensis remains. Each also contains layers of volcanic matter and ash. Radioactive argon in that volcanic material decays at a steady rate. Measuring this rate of radioactive decay allowed scientists to estimate the fossils’ age.

Lucy lived an estimated 3.2 million years ago. Her species at Hadar and elsewhere existed from about 3.9 million to 3 million years ago. So Lucy was an especially early hominid — the oldest known at the time of her discovery.

Educators and Parents, Sign Up for The Cheat Sheet

Weekly updates to help you use Science News Explores in the learning environment

Thank you for signing up!

There was a problem signing you up.

Make a good name for yourself

Lucy’s worldwide fame also was boosted by a catchy, memorable name.

Johanson and Gray’s discovery was a momentous occasion. When they returned to camp with what looked like pieces of a hominid skeleton, the whole team celebrated. As they partied, a tape recorder played the Beatles song “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” over and over. The tune’s psychedelic lyrics echoed the surreal events of that day. Joyous partyers started calling the newfound fossil Lucy.

The modern name, familiar to people around the world, gave Lucy a big boost toward fossil stardom.

Her naming was far from typical. Most fossil hominid specimens get named for the place where they were found.

Do you have a science question? We can help!

Submit your question here, and we might answer it an upcoming issue of Science News Explores

Consider the Taung Child. This 3-year-old’s fossil skull was found by miners at South Africa’s Taung quarry. It was unearthed in 1924 — a full 50 years before Lucy. And its discovery, researchers generally agree, launched the modern era of fossil-hominid studies.

The Taung skull was used to describe A. africanus as a new species. It turned researchers’ attention away from Asia and toward Africa as the birthplace of hominids. And its shape hinted that early hominids adopted a two-legged gait before evolving big brains.

But despite its scientific importance, the Taung Child never achieved Lucy’s public fame.

Lucy goes by other names. Her formal scientific designation is AL 288-1. Ethiopians today refer to the remains as Dinknesh. In a regional language, this means “you are marvelous.” But on the world stage, the Hadar female is best known as Lucy.

Get people talking

Though Lucy’s skeleton is incomplete, it revealed some of her species’ anatomy. Those clues were enough to reshape longstanding debates about hominid evolution. But they didn’t supply easy answers. Five decades later, those disputes continue.

At the time of the Hadar find, one family dominated anthropology: the Leakeys. Louis and Mary Leakey and their son Richard had many ideas about human evolution. Louis Leakey thought all human evolution occurred within the Homo genus. One Homo species led to the next to the next, he argued. They didn’t branch or lead to dead-end lines. In this view, australopithecines (Aw-STRAAL-oh-PITH-ih-seens) — such as the Taung Child — represented extinct ape species.

Big brains powered the rise of the Homo genus, the Leakeys argued. That started in Africa perhaps 3 million years ago. Eventually, it led to today’s humans.

Lucy challenged their idea. Here was a body built for humanlike walking, topped by an apelike brain. Johanson suggested her species marked a dramatic split in hominid evolution. A. afarensis evolved in one direction, he proposed — into later australopithecines. It also evolved in another direction into the Homo genus.

He and many others still hold that view today.

Lucy’s partial skeleton triggered other disputes as well. Her spine and legs were adapted for an upright gait. That might make it seem more likely that she was a direct Homo ancestor. But she also had relatively long arms and curved fingers. They resembled those of a tree-climbing ape.

So how did Lucy prefer to get around? Researchers have debated whether her species spent time in the trees or mainly stayed on the ground.

Some bone data suggest she had exceptional upper-body strength. That could support a controversial proposal that she fell to her death from high up in a tree. But another A. afarensis fossil find suggests a two-legged stance would have kept Lucy grounded. If so, she probably died from some other cause.

Make the right scientific friends

Lucy attracted big-time researchers right from the start. All that attention from well-known admirers helped her scientific status soar.

Johanson was Lucy’s first champion. He arrived at Hadar in 1972 as part of an international team of fossil-hunting superstars. The team worked at the site for years and excavated many Hadar fossils. Johanson went on to found the Institute of Human Origins, now at Arizona State University in Tempe.

Johanson also recruited a young researcher to help analyze the ancient bones. Tim White would go on to have a bright career as a paleoanthropologist. He helped Johanson identify Lucy and other nearby fossils as a new species. Years later, White helped excavate a 4.4-million-year-old partial hominid skeleton known as Ardi. Like Lucy, Ardi also shook up the human family tree.

Johanson took a very active role in bringing science to the public eye. He co-wrote a book in 1981, Lucy: The Beginnings of Humankind. It brought her worldwide attention. The same year, he debated Richard Leakey on television, moderated by Walter Cronkite (an extremely trusted and popular newscaster).

That year, too, Johanson met anthropologist William Kimbel. Kimbel became the best Homo sapiens friend Lucy and her kind could ask for.

Kimbel took charge of a new phase of fieldwork at Hadar in the 1990s. For the next 30 years, he raised money for, organized and directed excavations of A. afarensis. He detailed differences between hominid species and what they meant for primate evolution.

Kimbel and Johanson both argued that Lucy is a direct ancestor of the Homo genus.

During his televised debate with Richard Leakey, Johanson showed a drawing of his proposed hominid family tree. Leakey scrawled a question mark over it. Decades later, the shape of this tree and Lucy’s place in it remain controversial.

No matter how these questions play out, one thing is clear: Lucy’s trip from a Hadar gully to an Ethiopian museum vault has been a key piece of the journey to understand the origins of humankind. Fifty years after stopping a pair of fossil hunters in their tracks, Lucy’s star power still shines bright.