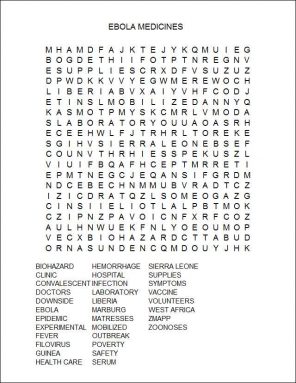

Ebola treatments and vaccines could be near

Ending the outbreak in West Africa might depend on treatments still being tested

Volunteers spray a disinfectant to prevent transmission of the Ebola virus.

afreecom/Idrissa Soumaré/EU Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection/Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0

By Nathan Seppa

Last December, a viral infection set off the first-known outbreak of Ebola in West Africa. As of August 22, nine months later, 2,473 people have taken ill — 1,350 have died. It’s far and away the biggest epidemic ever of this horrific, hemorrhage-causing disease. And still there is no cure. But a number of therapies appear near. All are still experimental, meaning that until this outbreak, they’ve never been tried on people. But scientists see hope that at least some of these drugs and vaccines might soon be mobilized, bringing the current outbreak to an end.

Make no mistake, it will take months to test, produce and bring the therapies to clinics. But researchers hold out hope that these products — even if incompletely tested — might help to slow the illness. Margaret Chan is the Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO), based in Geneva, Switzerland. Two weeks ago, she declared the current outbreak “a public health emergency of international concern.” That’s because it has gone on longer than any earlier Ebola epidemic. It has affected more people. And it still is not under control.

Indeed, health officials and other experts say the situation in West Africa is so bad that putting experimental therapies into use might be well worth the risk. Currently, at least half of all people there who have developed Ebola have died.

However, if the drugs do work, they might encourage people with symptoms — and friends and family they may have exposed — to come to hospitals. Keeping people under treatment, and quarantined, is the best hope of stopping the spread of this very lethal virus.

What’s more, making experimental drugs available — especially the disease-preventing vaccines — could help recruit more health-care workers to clinics and hospitals. Many more are needed to treat the sick. Yet all doctors, nurses and cleaning crews know their work puts them at high risk of catching the virus.

Who is getting sick

This year’s outbreak has hit a thickly populated part of West Africa. It has spread among the neighboring countries of Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone. None had ever encountered Ebola. And even before the disease struck, many people in these countries were suffering. The reasons: This region has a very high rate of poverty. Civil wars have caused many people to distrust each other and their governments. And all of the countries had weak health-care systems even before Ebola arrived. Now, conditions are even worse because some health-care workers have gotten sick or left hospitals out of fear of becoming infected.

“You get into a negative cycle in which it becomes a riskier environment for the nurses who do choose to keep working,” he says. “That happened in Kenema.” In some parts of Sierra Leone, basic public health measures — clinic care and quarantines — appeared to be slowing the outbreak. But not here. He said that conditions had spun out of control in the region that this hospital served.

New drugs may help

A few Ebola victims recently received one experimental drug. Doctors treated six people in Africa with ZMapp. It’s a mix of antibodies made by Mapp Pharmaceutical of San Diego, Calif. But all supplies of that compound are now gone. Making more will take months. So the World Health Organization and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services have pulled together experts to review research on other candidate drugs and vaccines. The goal is to identify ones that might be put into rapid safety tests, says Bausch.

Having a drug, even an imperfect one, could have a big impact beyond the treated patients, says Bausch. Why? Many people who have been exposed to Ebola patients, but show no signs of sickness, hesitate to get tested for the virus. They figure hospitals can’t cure them and going to a hospital may keep them from their jobs or taking care of their families. But refusing to get tested risks further spread of the disease, Bausch says.

Knowing a drug is available, however, could prompt people to come in for testing. Treating them and keeping them from exposing others “could end the outbreak,” he says.

To date, most experts have given their support for using experimental drugs such as ZMapp on Ebola patients. But the use of such drugs could still leave scientists with a poor understanding of how useful they are. The reason: About half of Ebola patients in West Africa survive without treatment, notes Kevin Donovan. He’s a doctor at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. So scientists will have a hard time identifying which patients a drug helped, and which would have gotten better without it.

Medicines, like those anti-viral drugs, are designed to fight a sickness that someone already has. Vaccines are different. They rev up the body’s infection-fighting immune system so that it can later recognize and fight a particular infection. Researchers have been working on Ebola vaccines for many years. Human safety testing of two of those experimental vaccines could begin late next month. That’s what WHO Assistant Director-General Marie-Paule Kieny reported at an August 12 news briefing.

One vaccine comes from Canada’s National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg, Manitoba. That lab announced last week it will make available 800 to 1,000 doses of a vaccine that worked well in monkeys. U.S. government labs and the drug company GlaxoSmithKline are preparing a second vaccine for human safety tests.

The World Health Organization will oversee who gets any test vaccines. There are no plans to use any of them until sometime next year. Doctors, nurses and other clinical staff will be at the front of the line for such shots, says William Schaffner. He’s an infectious-disease doctor at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn.

Having a vaccine also could encourage health care workers to stay on the job, says Thomas Geisbert. A virologist, he works at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston.

Another group of people slated to get the vaccines early: laboratory workers and those burying bodies. To date, nearly one in every 10 Ebola deaths in West Africa involved such people, Kieny reports.

But a lightly tested vaccine would require warnings. No one knows if a single dose will protect fully, Schaffner says. That means any vaccinated health-care workers will still have to keep their guard up. They will need to continue to don biohazard suits — those full-body “moon suits” — and take other precautions.

Finally, some researchers are working to create a “convalescent serum.” It would be derived from the blood of people who got Ebola and survived. Their blood should carry antibodies against the virus. Work on this treatment, however, is still in its early stages, Bausch notes.

Worst one yet

Two dozen Ebola outbreaks have hit Africa since 1976. The current one has caused far more deaths than any other. And this has surprised some experts. The reason: Health officials have approached this epidemic just as they have those in the past. They have carefully identified infected people and then isolated them. They have traced who the sick people had been in contact with, and watched them for 21 days (the time it takes to know whether the virus has infected someone). Finally, health-care workers wear spacesuit-looking biohazard gear when monitoring most of the sick or when handling dead bodies.

So what went wrong?

“Resources were spread pretty thin early on,” says Geisbert. So keeping track of everyone an Ebola victim has recently contacted has not been possible in West Africa.

Episodes of lawlessness have made matters worse. Last weekend, for instance, looters stormed a Liberian hospital. They left with mattresses and other infected supplies. Now, these people and anyone who contacts those materials risk becoming Ebola’s next victims.

Power Words

antibody Any of a large number of proteins that the body produces as part of its immune response. Antibodies neutralize, tag or destroy viruses, bacteria and other foreign substances in the blood.

biohazard An infectious agent or toxic material that can cause disease. It may be present as an isolated collection of germs or as tainted blood, urine or other materials.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC An agency of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC is charged with protecting public health and safety by working to control and prevent disease, injury and disabilities. It does this by investigating disease outbreaks, tracking exposures by Americans to infections and toxic chemicals, and regularly surveying diet and other habits among a representative cross-section of all Americans.

convalescence The recovery period after a sickness or injury.

Ebola A family of viruses that cause a deadly disease in people. Most cases occur in Africa and Asia. Its symptoms include headaches, fever, muscle pain and extensive bleeding. The infection spreads from person to person (or animal to some person) through contact with infected body fluids.

epidemic A widespread outbreak of an infectious disease that sickens many people in a community at the same time.

hemorrhage (adjective is hemorrhagic) Related to major or uncontrolled bleeding, often internally.

infection A disease that can spread from one organism to another.

microbiology The study of microorganisms, principally bacteria, fungi and viruses. Scientists who study microbes and the infections they can cause or ways that they can interact with their environment are known as microbiologists.

RNA interference A technique used to identify the chemical blueprint of gene, or to reduce the activity of a targeted gene.

vaccine A biological mixture that resembles a disease-causing agent. It is given to help the body create immunity to a particular disease. The injections used to administer most vaccines are known as vaccinations.

virus Tiny infectious particles consisting of RNA or DNA surrounded by protein. Viruses can reproduce only by injecting their genetic material into the cells of living creatures. Although scientists frequently refer to viruses as live or dead, in fact no virus is truly alive. It doesn’t eat like animals do, or make its own food the way plants do. It must hijack the cellular machinery of a living cell in order to survive.

World Health Organization An agency of the United Nations, established in 1948, to promote health and to control communicable diseases. It is based in Geneva, Switzerland. The United Nations relies on the WHO for providing international leadership on global health matters. This organization also helps shape the research agenda for health issues and sets standards for pollutants and other things that could pose a risk to health. WHO also regularly reviews data to set policies for maintaining health and a healthy environment.