DEET confuses mosquitoes

Scientists suspect the repellant messes with a mosquito’s sense of smell

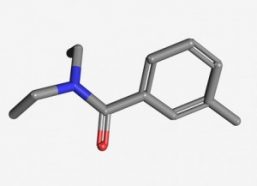

DEET is an insect repellant that fights biting backyard bugs like ticks, chiggers and mosquitoes. A DEET-treated arm can spare a person from an itchy bite, and in a new study, scientists suggest that the repellant works so well by targeting a bug’s sense of smell.

“The effects of DEET are not straightforward,” Maurizio Pellegrino told Science News. “We think…the insect doesn’t know exactly what it is smelling.” Pellegrino is a neuroscientist — someone who investigates the brain and the nervous system — at the University of California, Berkeley. He worked on the DEET projects while at Rockefeller University in New York City.

People have been using DEET for decades, and the chemical seems to work from both short and long distances. On the skin’s surface, the repellant drives away bugs looking for a blood meal. But it can also keep bugs from ever getting close enough to land. Scientists have disagreed on why the stuff works so well.

Insects like mosquitoes — and fruit flies, which were the lab animals used in the recent experiment — don’t have noses or pick up smells by sniffing. Instead, they have spots, or receptors, on their antennae that can pick up the chemical signature of an odor in the air. These receptors send information about the smell to the brain by way of a nerve, which looks like a tiny thread and shuttles information through the body.

Pellegrino and his colleagues found that the bugs’ smell-detectors were affected when DEET was around. The nerve cells sent different signals to the brain depending on whether DEET was detected alone or together with other scents. The repellant seemed to block the bugs’ ability to detect other smells. In addition, the insects appeared to be able to detect varying amounts of DEET. As a result, the researchers concluded that DEET somehow alters the smell information sent to the brain. That means DEET doesn’t necessarily drive bugs away — it just confuses them so much that they fly away.

“It’s as if you are hungry and you love hamburgers,” Pellegrino told Science News. “If DEET is present, it doesn’t smell like hamburger anymore, even if a hamburger is right in front of you.”

POWER WORDS

nerve A whitish fiber or bundle of fibers that transmits impulses of sensation to the brain or central nervous system, and impulses from these to the muscles and organs.

antenna (plural: antennae) Either of a pair of long, thin sensory appendages on the heads of insects, crustaceans and some other arthropods.

cell The smallest structural and functional unit of an organism, typically microscopic.

neuroscience Any of the sciences that deal with the structure or function of the nervous system and brain.