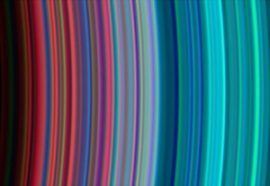

Ripples in one of Saturn’s rings

Scientists study pattern created by 600-year-old comet crash

No one on Earth noticed when a comet plowed through Saturn’s rings and blasted them apart. Of course we missed it: The flying “dirty snowball” broke up 600 years ago. That’s more than 200 years before Galileo Galilei first gazed through the telescope and mistook Saturn’s legendary rings for handles or mammoth moons.

Those rings circle the planet like an oversized phonograph record. They appear still and spooky in photographs. But don’t be fooled: They’re actually vast seas of individual rocks. Just as an object creates waves when it splashes in water, the comet disturbed the rocky rings on its final flight. Patterns in Saturn’s rings allow astronomers to learn about the planet’s past.

At a recent meeting of astronomers in France, Essam Marouf told the story of the Saturn-bound comet that blew apart in the late 1300s. Marouf works at San Jose State University in California. As an engineer, he builds or works with technical machinery to answer scientific questions or solve problems. Marouf collaborates with scientists working on the Cassini spacecraft, which orbits Saturn. Cassini has been beaming back information about the planet and its moons and rings. Even though astronomers missed the smashup six centuries ago, he said the comet created ripples in the rings that persist.

“There were highly regular little wiggles that rippled over hundreds of kilometers in a very specific pattern,” Marouf told Science News.

Marouf’s team found the ripples in Saturn’s C ring. It’s a faint band inside the more familiar and giant A and B rings. Over time, the ripples bunched up. Marouf reported that the distance between individual waves now measures more than three times the height of the Empire State Building. Knowing how these kinds of waves get closer over time, Marouf and his team were able to calculate when the waves began.

The scientists didn’t see the ripples in pictures. Instead, they found telltale disturbances in radio waves. In an experiment, Cassini sent radio transmissions to Earth. But first they traveled through Saturn’s rings. As radio waves zoomed through the C ring, they picked up what Marouf called a “very unusual kind of addition.” It turned out to be the ripples.

Other ripples, much farther apart, also disturb Saturn’s C ring and are probably from other wayward comets. Scientists found similar waves in the rings of Jupiter too. In the case of the 600-year-old ripples on Saturn, Marouf and his team identified two distinct wave patterns of similar sizes, which suggests the plunging comet passed twice near the ring and never had a chance of escape the second time.

“Some object got captured into orbit, made two close passages. Survived the first, not totally damaged — then 50 years later it came back in and that was the end of it,” astronomer Mark Showalter told Science News. Showalter works at the SETI Institute in Mountain View, Calif. And he knows about comets and rings. He connected the ripples in Jupiter’s rings with the 1994 demise of a comet called Shoemaker-Levy 9.

POWER WORDS

radio The sending and receiving of radio waves, which are longer than waves of visible light and are used to carry information over long distances.

comet An object that flies through space and consists of a core of ice and dust. When near the sun, a comet has a “tail” of gas and dust particles pointing away from the sun.

phonograph record A thin plastic disk carrying recorded sound, especially music, in grooves on each surface, for reproduction by a record player.

orbit The curved path of an object in space or spacecraft around a star, planet or moon.