Back off the bacon and cold cuts?

A new report from the World Health Organization links cancer to regularly eating certain meats

Bacon sizzles on the griddle. A new report connects regularly eating this and other processed meats with an increased risk of a serious cancer.

Chris Yarzab / Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

In October 2015, bacon lovers around the world panicked. A major international health group issued a report saying that eating processed meats may contribute to cancer. These foods include bacon, cold cuts, hot dogs and other types of sausages. People who eat too much red meat (such as beef) and processed meats daily face an increased risk of a deadly cancer, the new report concluded.

The report came from the World Health Organization, or WHO. An agency of the United Nations, it’s based in Geneva, Switzerland. A group of 22 WHO experts reviewed findings from more than 800 studies. Their conclusion: Eating too much red meat — including beef, pork, or goat — likely leads to cancer.

The news media gave the new report lots of attention. “Bad day for bacon,” said one headline. “Bacon causes cancer,” read another. One even said, “Processed meats rank alongside smoking as cancer causes.”

Is eating bacon really as dangerous as smoking? No. Smoking is still much, much worse. Do people need to stop eating red meat and processed meats altogether? Again, no, although diners may want to limit how much they eat.

Joan Salge Blake agrees. She’s a nutrition expert at Boston University in Massachusetts. Turning the WHO report into useful advice takes a broad perspective, she says.

“What does it mean for Joe and Josephina on the street? It’s interesting,” says Blake. “I think we can look at these findings and say, maybe what we need to do is is mix up a little bit of what we’re eating.” In other words, “Eat a wider variety of foods.” People may run into a problem when they eat “too much of these processed meats, and not enough fruits and vegetables,” she says. Enjoying bacon or a hot dog once in a while won’t cause problems. But a daily meal of them just might, she says.

Blake describes the new report as “another little piece in the big puzzle” linking diet and disease.

What the WHO report says

Fifty grams. That’s a key number to remember from the WHO report. The experts reported that people who eat 50 grams (a little under 2 ounces) of processed meat each day had a higher risk of colorectal cancer.

The colon is another name for the large intestine. And the rectum is the tail end of the large intestine. (The rectum is the last place waste goes before it leaves the body as feces, or poop.) Colorectal cancer starts in either the colon or rectum. Cells grow out of control and form clusters, called tumors. Cancerous cells may enter the bloodstream, travel to other places in the body, and then launch new tumors there.

In general, about five out of every 100 people in the United States will at some point be diagnosed with colorectal cancer. Most diagnoses occur in people older than 50. African Americans face higher rates of the disease than do people from other ethnic groups. But this cancer is serious. About two of every 100 Americans die from the disease.

WHO’s 50-gram warning equates to two strips of bacon. It’s about two slices of ham or one jumbo hot dog.

But don’t panic. Eating two strips of bacon one morning won’t increase your risk of cancer. The risk comes from eating it every day. And even then, the WHO reported, eating 50 grams of processed meat daily raises a person’s risk of colorectal cancer by about 18 percent.

What does that mean? The new WHO report suggests that six in every 100 people who eat 50 grams of processed meat every day will one day be diagnosed with colorectal cancer. And for every additional 50 grams of processed meat someone regularly eats each day, their cancer risk will climb by another 18 percent.

“Some headlines have suggested that bacon is as dangerous as smoking,” says Frank Hu. In fact, he says, “that’s grossly exaggerated.” Hu is a doctor and researcher at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Mass. He studies the links between nutrition and disease.

The WHO team found strong evidence of the link between processed meats and cancer. The evidence was as strong as the evidence linking tobacco use to cancer. Both substances are carcinogens. That means studies have shown they can cause cancer. Even though the evidence was equal, the potency of the risk each poses was not. Headlines equating bacon’s danger to smoking is simply wrong.

At the same time, Hu says people shouldn’t ignore the WHO’s report. The risk from eating processed meats builds up, year after year. So the risk posed by eating unhealthy foods over a lifetime will grow with each advancing year, says Hu. That’s why, he notes, “It’s really important to develop healthy eating habits at a young age.”

The WHO isn’t the only major group that advises people on healthy eating. On January 7, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Department of Health and Human Services updated the dietary guidelines for all Americans. These recommendations aim to keep people healthy.

In the newest version, the two government organizations recommend that people eat a variety of fruits and vegetables and low-fat dairy products. They advise people to get their protein from a variety of sources, including seafood, lean meats and soy. Some critics have argued that these new guidelines should have advised more strongly that people cut their meat intake.

Understanding the link between diet and health is complicated. A December 30, 2015 study in Nutrition Journal looked at eating habits in more than 15,000 people. On average, kids and adults who ate lunch meats — which often are processed meats — downed more calories than did people who don’t eat lunch meats. But, they also found that people who ate lunch meats were less likely to be obese. And eating lunch meats did not necessarily reflect a preference for junk foods. So lunch meats can be part of a healthy diet, the authors concluded.

Of meat and cancer

Turesky, Blake and Hu were not surprised by the WHO report. Scientists have reported for decades that people who eat a lot of red meat or processed meats face a higher risk of many types of cancer.

Hu says the report is based on good science: “It summarizes all the evidence that has accumulated in the last two decades.” It’s conclusion, he adds, is that ”regular consumption of processed meats is carcinogenic.”

Keep in mind, eating red meat has nutritional benefits. It contains protein, which the body uses to build maintain muscles and bones. Red meat also provides iron to help the body make red blood cells.

But it’s possible to eat too much of a good thing.

Researchers don’t yet understand why eating these meats leads to cancer. They do have some ideas, though. Red meat is often high in saturated fat, which has been linked to colorectal and breast cancers. Some studies suggest the type of iron found in red meat can also damage cells. And that, too, might lead to cancer. The new USDA and HHS guidelines recommend that people limit their intake of saturated fats. And to do that, diners would have to keep their intake of red meat low.

In the case of processed meats, it’s that processing that can boost health risks. According to the WHO, almost all processed meats contain beef or pork. However, they might also contain other kinds of meat, poultry, internal organs or blood. “Processing” means the meat has been treated in some way. It may have been salted, cured, fermented, smoked or otherwise ”cured.” A hot dog, for example, contains curing salts and chopped meat. After being stuffed in casings, its meat is cooked and smoked. The process improves flavor and gives the sausage a longer shelf life.

Disease risk may link to several aspects of these meats. Processed meats might contain chemicals called preservatives. Not all preservatives are harmful, but some may damage cells. For instance, some studies indicate that the body can transform the nitrites used as preservatives in many hot dogs into carcinogens.

But carcinogens do not always cause cancer. Whether they do may depend on how much of them are eaten and over what period of time.

What’s more, some cancer-causing chemicals are worse than others. And not all of them will affect everyone the same way.

For example, “not everyone who smokes tobacco gets cancer,” notes Turesky. Factors such as a person’s genes help influence whether or not cancer develops. That’s one reason it’s difficult to know exactly how carcinogens will affect any particular person. What’s more, scientists can’t deliberately expose many people to a cancer-causing substance — and then wait to see who gets sick. Instead, they have to look for patterns that turn up a link between diet and disease in large groups of people who had eaten what they wanted. Those are the groups that the WHO experts have just analyzed.

Turesky says nutrition scientists are now conducting studies to better understand how red meats and processed meats cause cancer. “We’d still like to know, is it specific chemicals in these products or combinations that cause cancer? Are there ways to minimize the health risks? Are there things we can eat that can protect us against these types of carcinogens?”

These are important points. Many studies have shown, for instance, that the way meats are grilled can affect the production of heterocyclic amines, or HCAs. For instance, eating certain starchy foods along with meats containing those HCAs appears to cut the chance the HCAs will trigger cancer-related changes.

Large studies aimed at answering all of these questions could help health groups offer better diet or cooking recommendations.

Pro tip: Get cooking

The WHO report “frightens parents. Of course it does,” Blake admits.

“Kids need to learn how to cook so they can learn about foods and flavors and be prepared to deal with their diets as young adults,” she says. Home cooking also helps kids maintain a healthy body weight. Past studies have reported that kids and adults who eat fast foods — such as hot dogs, burgers and French fries — face a higher risk of becoming overweight or obese. And obesity is linked to many ails, including heart disease, diabetes and some types of cancer.

According to data released in November 2015 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, rates of obesity in the United States are at an all-time high. Nearly 17 in every 100 children are obese. And among U.S. adults, the rate is more than twice that high.

Clearly, warns Blake: “We’re not getting better about obesity.”

She hopes the new WHO report serves as a wake-up call for people to make better choices about food. “I’m not saying that means we should give up ham and cheese sandwiches. I’m just saying, maybe we need to moderate what we eat. Maybe we can tone down our diets a little.”

Power Words

(for more about Power Words, click here)

cancer Any of more than 100 different diseases, each characterized by the rapid, uncontrolled growth of abnormal cells. The development and growth of cancers, also known as malignancies, can lead to tumors, pain and death.

carcinogen (adj. carcinogenic) A substance, compound or other agent (such as radiation) that causes cancer.

casing (in food science) The outer skin or material used to hold — or encase — the meat and other ingredients used to make a sausage.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) An agency of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC is charged with protecting public health and safety by working to control and prevent disease, injury and disabilities. It does this by investigating disease outbreaks, tracking exposures by Americans to infections and toxic chemicals, and regularly surveying diet and other habits among a representative cross-section of Americans.

cold cuts Various types of meats, such as salami and bologna, that are typically cured and then served cold.

colon (in biology) The majority of the large intestine, it runs between the cecum (a pouch below the small intestine) and the rectum. Foods are not digested in the colon, although this tissue lubricates wastes that will be excreted. Some liquids and salts, however, will be removed from materials stored in the colon before excretion.

cure (in food science) To treat foods so that they resist spoilage and food-poisoning microbes. Types of processes used for curing foods include pickling, smoking, drying and treating with chemicals such as nitrates (or nitrates) and sulfates.

diabetes A disease where the body either makes too little of the hormone insulin (known as type 1 disease) or ignores the presence of too much insulin when it is present (known as type 2 diabetes).

ethnicity (adj. ethnic) The background of an individual based on cultural practices that tend to be associated with religion, country (or region) of origin, politics or some mix of these.

fermentation (v. ferment) The metabolic process of converting carbohydrates (sugars and starches) into short-chain fatty acids, gases or alcohol. Yeast and bacteria are central to the process of fermentation. Fermentation is a process used to liberate nutrients from food in the human gut. It also is an underlying process used to make alcoholic beverages, from wine and beer to stronger spirits.

gene (adj. genetic) A segment of DNA that codes, or holds instructions, for producing a protein. Offspring inherit genes from their parents. Genes influence how an organism looks and behaves.

heterocyclic amines A class of at least 17 chemicals that can form when meat is cooked at high temperatures. In 2005, a U.S. government review of scientific data concluded that at least some of these cause colon cancer in animals, and likely do the same in people. These compounds form in chemical reactions between several food constituents, such as the simple sugar glucose, the amino-acid creatinine and additional free amino acids. Meat contains all of those ingredients.

media (in the social sciences) A term for the ways information is delivered and shared within a society. It encompasses not only the traditional media — newspapers, magazines, radio and television — but also Internet- and smartphone-based outlets, such as blogs, Twitter, Facebook and more. The newer, digital media are sometimes referred to as social media.

nitrites Chemicals that contain nitrogen and are added to processed meat to prevent bacterial infection and prolong shelf life. Nitrites are also used in some fertilizers.

nutrients Vitamins, minerals, fats, carbohydrates and proteins needed by organisms to live, and which are extracted through the diet.

nutrition The healthful components (nutrients) in the diet — such as proteins, fats, vitamins and minerals — that the body uses to grow and to fuel its processes.

obesity Extreme overweight. Obesity is associated with a wide range of health problems, including type 2 diabetes and high blood pressure.

processed meats Meats that have been preserved by smoking, curing, salting or treating with some type of preservative to avoid spoilage. Examples include ham, bacon, pastrami, and sausages such as salami.

red meat A term used to describe beef, lamb or other meats that appear red when uncooked — and not light colored (as chicken breast is) when cooked.

rectum The final section of the large intestine, terminating at the anus.

saturated fat A type of dietary fat, often derived from animals. Owing to its chemistry, this type of fat tends to be solid at room temperature. Examples include butter, lard, solid shortening and coconut oil. Eating too much of these types of fat has been linked with heart disease, type 2 diabetes and certain cancers (principally breast cancer).

tumor A mass of cells characterized by atypical and often uncontrolled growth. Benign tumors will not spread; they just grow and cause problems if they press against or tighten around healthy tissue. Malignant tumors will ultimately shed cells that can seed the body with new tumors. Malignant tumors are also known as cancers.

United Nations Created in 1945, just after the end of World War II, it’s a group of nations that work together for common goals, such as providing a cleaner environment, improving human rights, improving world health and fostering world peace. Currently, 193 nations belong to the United Nations.

World Health Organization An agency of the United Nations, established in 1948, to promote health and to control communicable diseases. It is based in Geneva, Switzerland. The United Nations relies on the WHO for providing international leadership on global health matters. This organization also helps shape the research agenda for health issues and sets standards for pollutants and other things that could pose a risk to health. WHO also regularly reviews data to set policies for maintaining health and a healthy environment.

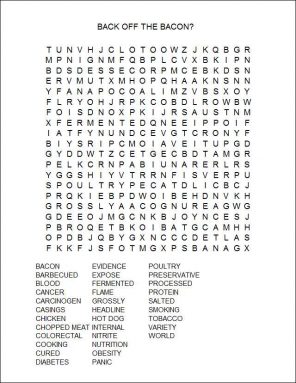

Word Find (click here to enlarge for printing)