Sizing up the Kuiper belt

With the help of students and amateur astronomers, scientists are learning more about the unusual objects, such as the Kuiper belt, at the edge of our solar system.

NASA

In the wee hours of May 4, 2013, small groups of people from northern California to the southern end of Nevada gathered around 14 telescopes. Some were high school students, some were amateur astronomers and some were just interested in space. All shared the same goal: to carefully watch one particular star — and record if and when it briefly disappeared.

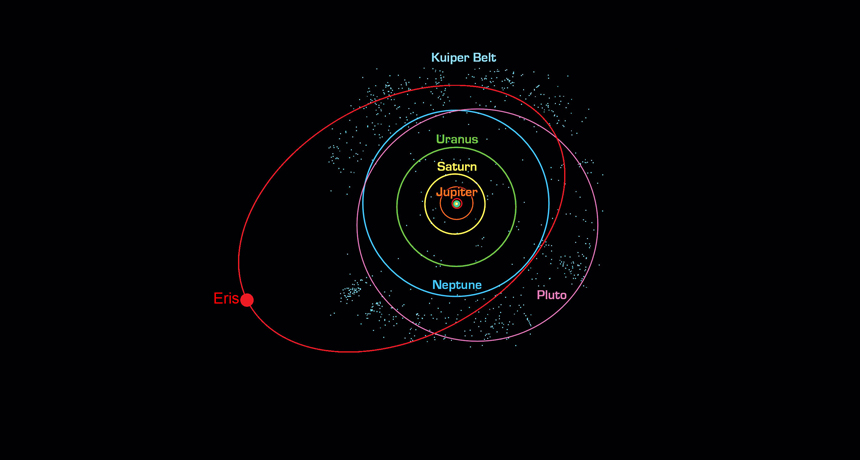

These stargazers were recruited by RECON, the Research and Education Cooperative Occultation Network. RECON has been focusing its attentions on the Kuiper belt, a broad ring of objects orbiting the sun just beyond Neptune, more than 4.4 billion kilometers (2.7 billion miles) away. Made of rocks, ice, frozen methane and ammonia, they range in size from gritty dust bits to dwarf planets, including Pluto.

Scientists have discovered thousands of Kuiper Belt objects, or KBOs, but know very little about them. RECON hopes to change that. Organized by scientists at the Southwest Research Institute (SWRI) in Boulder, Colo., and the California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo, it is recruiting “citizen scientists” —non-expert volunteers — to help quantify the size of these KBOs.

To do that, RECON records events where a KBO passes between Earth and some distant object, such as a star. When this happens, it will look like the star has disappeared. Such an event is called an occultation. Even though both the KBO and the star it eclipses are just tiny dots in the night sky, you don’t need a giant telescope to witness an occultation. Even relatively simple telescopes, like the ones RECON uses, will do.

A star’s vanishing act can tell scientists a great deal. How long a star disappears will depend on the size of the KBO that passes in front of it. Scientists can use the KBO’s distance and the length of the occultation to calculate the diameter of the KBO.

And that is the goal of RECON. “We want to figure out the sizes of these objects,” explains Marc Buie. He’s a researcher at SWRI who is on RECON’s team of organizers. “Once you know the size of an object and its mass,” he says, “you can figure out the density of the object.” And that can help scientists figure out what the object was made up of. For instance, it can help narrow down whether the KBO is made of mostly ice or mostly rock.

The first step in that process is to begin cataloging the size of individual KBOs by watching for and timing occultations. And to get those data, RECON sends out telescope teams to many different places at once. Based on what they already know about KBOs, the scientists can predict where and when an occultation should occur. But these are only predictions. Many factors, including cloud cover and geography can influence who will be able to see a particular occultation.

With the help of high school students and other citizen scientists across the western United States, RECON now can collect data on an occultation from up to 10 sites at once. The research group donates a telescope, timer and a video monitor to each team to record what it sees. RECON warns each group when to expect the occultation and where to train its telescope. Each team then heads outside at the same time and reports whether the star blinked out. And if so, for how long?

On their first official RECON test in May, the teams all trained their telescopes on a star named P130504. It appears near the constellation Sagittarius. Then they waited for Pluto — the dwarf planet and most famous KBO — to cross in front of it. Mountain ranges blocked the view for some of the teams. Others were too far north, so the star wasn’t visible above the horizon. In the end, not one team observed the occultation.

And this isn’t uncommon, Buie says. On any given night, most teams will watch in vain. But even that’s worth reporting. “They will have data that says ‘it didn’t happen here,’” he notes, “and that’s valuable information.” Fortunately, more recent tests have succeeded in seeing occultations. For example, in November, RECON recorded the occultation of a star by a non-Kuiper belt object (an asteroid orbiting between Earth and Mars).

RECON has had no trouble signing up volunteers. “The enthusiasm and the responses we’ve been getting have been overwhelmingly positive,” Buie says. “We had to scramble to figure out how to say yes to everybody.” Although the participants volunteer their time, it still costs plenty of money to run this program. The National Science Foundation has paid for telescopes, video monitors, travel for the scientists and training of the volunteers. Buie is hopeful his group can get more funding to scale up. That way RECON can donate additional telescopes, allowing more viewing teams to scout for any given occultation.

RECON has had to turn away many eager volunteers in the Midwest and on the East Coast. The cloud cover common in this part of the United States means viewers often won’t have a clear night when they need one. The West’s long stretches of desert mean dry, clear skies are the norm.

“Ultimately,” Buie says, “we’re doing science. Every one of these events is unique, special and new. And the students have the ability to get involved in a front-rank science project to learn something new about the outer solar system.” Indeed, RECON’s efforts could supply crucial information about the size of objects at the edges of our solar system. Along the way, it also could get a lot of students excited about astronomy.

Power Words

ammonia A colorless gas with a nasty smell. Ammonia is a compound made from the elements nitrogen and hydrogen. It is used to make food and applied to farm fields as a fertilizer. Secreted by the kidneys, ammonia gives urine its characteristic odor. The chemical also occurs in the atmosphere and throughout the universe.

astronomy The science that deals with celestial objects, space and the physical universe as a whole. People who work in this field are called astronomers.

density A measure of the consistency of an object, found by dividing its mass by its volume.

gravity The force that attracts anything with mass, or bulk, toward any other thing with mass. The more mass that something has, the greater its gravity.

Kuiper Belt An area of the solar system beyond the orbit of Neptune. It is a vast area containing leftovers from the formation of the solar system that continue to orbit the sun. Many objects in the Kuiper Belt are made of ice, rock, frozen methane and ammonia.

mass A quantity that shows how much an object resists speeding up and slowing down — basically a measure of how much matter that object is made from.

Neptune The furthest planet from the sun in our solar system. It is the fourth largest planet in the solar system.

occultation Any event where an object is briefly hidden from view when another object passes in front of it. In astronomy, this usually refers to objects such as asteroids passing in front of a star.

Pluto A dwarf planet that is located in the Kuiper Belt, just beyond Neptune. Pluto is the tenth largest object orbiting the sun.

solar system The eight major planets and their moons in orbit around the sun, together with smaller bodies in the form of dwarf planets, asteroids, meteoroids and comets.

telescope A light-collecting instrument that makes distant objects appear nearer through the use of lenses or a combination of curved mirrors and lenses. Some, however, collect radio emissions (energy from a different portion of the electromagnetic spectrum) through a network of antennas.