Cool Jobs: Pet science

You don’t need to be a vet to work with cats or dogs

Dogs, cats and other animals can be important members of human families. Scientists study our pets, inside and out, so that the relationship can be a happy and healthy one.

vvvita/iStockphoto

A few years ago, a young Bengal cat was brought into the veterinary hospital at the University of California, Davis. Normally, when light shines into a cat’s eyes in the dark, the eyes appear to glow. But this kitty’s owner said the cat had unusual eye shine.

An animal ophthalmologist (OP-thoh-MOL-uh-jist) — a doctor that treats eyes — looked at the cat and discovered it was blind. He then called in Leslie Lyons. This cat geneticist, who now works at the University of Missouri–Columbia, studies DNA. Inside the cells of all living things, DNA holds the instructions for life.

Lyons and her colleagues began studying the cat and its relatives. All were born with normal vision, they found. Their blindness set in as they grew older. And the cause of the blindness was a mutation, or change, in a single gene.

“The cat,” Lyons notes, “is a model for human disease.” So are dogs and other animals. Understanding them and their genes can lead to treatments for human illnesses. But perhaps more importantly, pets matter because they are often more than just animals — they have been invited in to share the households of so many human families.

In the United States, we have a lot of these furry, scaled and feathered family members. There are 86 million cats, 78 million dogs and more than 100 million pet fish. And there are millions more horses, birds, reptiles and various small animals living with us.

Veterinarians and vet techs work to keep these animals healthy. They treat pets that are sick. But they aren’t the only experts who work with our cats, dogs and other animals. Here we meet three researchers who are working to keep our pets healthy and happy — and their owners, too.

Ninety-nine lives

From a young age, Lyons says, “I knew I wanted to be a scientist because I knew I always wanted to learn things.” But she didn’t set out to study cats. She got her PhD in human genetics. For her postdoctoral research, she worked at the National Cancer Institute. NCI is a government organization that studies human cancers. But researchers there discovered in the 1970s that a virus can cause cancer in cats. So NCI scientists began studying felines to see if they could provide insight into human disease.

“All mammals share their 19,000 genes or so. Very few are specific to a species,” Lyons explains. Whether an animal has a tail or whiskers, for example, depends on which of those genes are turned on or off. And because of that, she says, “Anything that we discover in a cat can absolutely be translated into something in humans as well.”

Lyons switched from studying humans to studying cats. Today, her “Lyons’ Den” lab at the University of Missouri focuses on finding mutations in cat genes that cause diseases or interesting traits. One example: the kinked tail of a Japanese bobtail cat.

Recently, Lyons has started a more ambitious project. She calls it “99 Lives.” That name is a play on a cat’s mythical nine lives. Lyons and other kitty researchers aim to sequence — chemically map — the genomes of 99 cats. (A genome is an organism’s entire set of DNA.)

A 4-year-old Abyssinian named Cinnamon was the first cat to have its genome sequenced. But while Cinnamon’s genes are similar to every other cat’s, they are not exactly the same. “Every genome is a little bit different,” Lyons points out. If scientists sequence the genomes of many cats, “then you start to understand … what are the important parts, what are the unimportant parts. Having one cat is a good start, but you need a bunch of cats to start understanding … the dynamics” — the variety and changes possible within those genes.

To sequence the genome of a cat or any animal, scientists start with a sample of tissue. Blood works well, and only a teaspoon or so is needed. They isolate DNA from inside the cells. That DNA ends up in pieces, in one big soup, Lyons explains. Chunks of DNA are taken out of the soup and sequenced. Analyze enough scoops and researchers will have most of the genome. Computer algorithms (sets of instructions) then assemble the partial sequences in order.

Having Cinnamon’s

complete sequence, all of the genetic letters — in order — makes it easier and cheaper to sequence the DNA of other cats.

Cinnamon “gives us a reference,” Lyons explains. “Having Cinnamon is like having the picture on the front of the puzzle box.” Cinnamon’s sequence tells scientists the general order of the genome in other cats. That lets them sequence the genomes of other cats in days, instead of years. And they can do it for thousands of dollars, instead of millions.

Lyons and other cat geneticists have sequenced 53 cats so far (though not her own two, Withers and Figaro). Some are sick. Others are not. If scientists want to find a mutation that makes a cat ill, they need cats without the mutation for comparison. They even have two wild cats in their genome collection, a Pallas’s cat and a black-footed cat. “Wild [cats] will help find the sicknesses in domestic cats and vice versa,” Lyons says. They also can provide insight into cat evolution.

The 53 genome sequences now in hand are a powerful resource, Lyons says. “We’d love to get hundreds or thousands.” And one day, sequencing cat genomes may be so cheap and easy that any cat owner can send off a bit of cat tissue to get a sequence. “There’s no stopping at 99,” she says. “We just had a clever name.”

There’s a good doggie

Dogs are the most common pets in U.S. households. (There are more cats overall because many cat households are home to more than one.) “Dogs have a very intimate role in our lives,” says Clive Wynne. They live in our houses and even sleep on our beds.

Wynne is an animal psychologist at Arizona State University in Tempe. For a long time, such scientists studied animals that were easy to keep in cages in the lab, such as pigeons and rats. But now they study all sorts of animals. Wynne chose to work on dogs, in part because he was interested in dog behavior. But he also wanted to know more about the relationship between animals and people.

“Trying to understand dog behavior, how dogs work, how dogs think — these things are fun. But they’re fun with consequences,” he says. A badly behaved dog might bite a person. And if its behavior is bad enough, it might be sent to a shelter or even put to death.

Genetic evidence suggests that the relationship between dogs and humans began at least 15,000 years ago. But in many ways, scientists know less about dogs than about the rats and pigeons that they studied for so long. “It’s just astonishing how many simple, straightforward questions any middle-schooler might ask about their dog have never been the subject of scientific study,” Wynne says.

For example: Do dogs prefer vocal praise (“You are such a good doggie!”) or being petted? The answer might seem obvious to a dog owner. But no one had ever given the question a serious test. So Wynne and his then-graduate student Erica Feuerbacher (now at Carroll College in Helena, Mont.) decided to find out.

In their first experiment, a dog was placed in a pen with two people. One offered vocal praise. The other would pet the dog whenever it came near. Dogs spent more time, on average, near the person who petted them than with the one who said nice things. Shelter dogs seemed especially fond of being petted. Dogs that had owners often preferred the praise at first, if the person praising them was their owner. But even they eventually chose to spend more time with the person who pet them.

Feuerbacher and Wynne then performed a second test. They let each dog roam near an experimenter who, when the canine approached, either praised the dog or petted it. The researchers recorded how much time the dog spent near the human. Again, dogs spent more time with people when they offered petting.

Dogs indeed prefer petting over vocal praise, the researchers concluded.

“If you think that you can reward a dog by telling it it’s a good dog, well, your training method is not going to be terribly successful,” Wynne says. This is important to know, he says, because training is important. It’s how we teach dogs to guide blind people or detect bombs. It’s also how we get better pets that don’t dig up the garden or eat the family roast.

Wynne still talks to his own dog, Xethos. “I think it does me good,” he says. “It doesn’t have to be always about her.” But, he adds, if you really want to motivate a dog, use food. It trumps everything else.

Don’t lick your turtle

Though pets usually bring their owners a lot of joy, sometimes animals also can transmit disease. Often such illnesses are preventable. But to know how to stop their spread, scientists first need to know who is getting sick and why. That’s where Tory Whitten and her colleagues at the Minnesota Department of Health in St. Paul come in.

As an epidemiologist (EP-ih-dee-mee-OLL-oh-jist), Whitten tracks diseases in her state. She focuses on zoonoses (ZOO-uh-NO-sees). These are diseases that can be passed between animals and people. Whitten and her colleagues work on public health. This is different from what doctors do. “A doctor or veterinarian focuses very specifically on what’s troubling a certain person [or animal],” she explains. In public health, “we look at the bigger picture,” she says. This includes the whole population, including its animals, people — even environmental factors.

One disease of concern is salmonellosis (SAM-muh-nel-OH-sis). It’s caused by Salmonella bacteria. When infected, healthy human adults may develop some stomach cramping and diarrhea. They’ll feel bad for a few days, but then quickly get better. Older people and those with weakened immune systems (such as diabetics or cancer patients) can get more seriously ill. And young children may develop complications. These may include bloodstream infections or meningitis. Indeed, Whitten notes, “Little kids and infants are more likely to be hospitalized.”

People often catch

Salmonella

from tainted food. But pets, especially reptiles, are another important source of the bacteria. They have been linked to

Salmonella

outbreaks that start at schools, zoos and even potluck dinners. Whitten and her colleagues wanted to know more about salmonellosis cases tied to reptiles. That might help her team head off infections.

Since 1996, Minnesota has collected reports of salmonellosis from doctors. Staff from the state’s health department then talk to the sickened people (or their parents, if it’s a child). They ask about where the patient had been, what foods they had eaten before getting sick and any animals they had been near. If the patient had come in contact with a pet reptile, the interviewer also asked about the pet.

Between 1996 and 2011, more than 10,000 people became infected with Salmonella. Of those, 290 people had contact with a reptile during the week before they got sick. Those reptiles included snakes, lizards and turtles. Two-thirds of the patients had been under the age of 20. Nearly one-third were under the age of 5.

In 70 cases, the researchers were able to test the reptiles for germs. And 60 of the 70 were infected with the bacteria. These animals can pick up Salmonella from their environment. Snakes also can get it from the mice they have been fed.

Researchers have known for years that reptiles can pass Salmonella to people. And experts have recommended that schools with little kids, and homes with children under age 5, not keep pet reptiles. But this study showed how important it is to make sure that message reaches the public. It will help guide the state’s health communications.

Whitten says she’d also like places that sell reptiles to be a little more up front about the fact that these animals can carry Salmonella — “and maybe even do a little bit more on screening the person that’s buying it and making sure they don’t have anyone under the age of 5.” People can largely avoid the disease by washing their hands after touching a reptile. Unfortunately, little kids aren’t very good at that.

When Whitten was growing up, she wanted to be a veterinarian. But she got interested in public health while in college. She’s still helping animals, she says, just in a different way. Her department works not only to keep people safe from diseases spread by animals, but also to keep animals safe from illnesses spread by people. “We totally understand the importance of a human-animal bond and learning about animals,” she says, “and think that’s really important.”

This is one in a series on careers in science, technology, engineering and mathematics made possible with generous support from Alcoa Foundation.

Power Words

(for more about Power Words, click here)

Abyssinian cat A breed of shorthaired domestic cat with brown fur, a slender body and large, pointed ears. The first cat to have its genome sequenced was an Abyssinian named Cinnamon.

algorithm A group of rules or procedures for solving a problem in a series of steps. Algorithms are used in mathematics and in computer programs for figuring out solutions.

bacterium (plural bacteria) A single-celled organism. These dwell nearly everywhere on Earth, from the bottom of the sea to inside animals.

Bengal cat A breed of domestic cat that looks like a small leopard. These cats are hybrids of domestic cats and wild Asian leopard cats.

black-footed cat The smallest species of wild cat in Africa.

canid The biological family of mammals that are carnivores and omnivores. The family includes dogs, wolves, foxes, jackals and coyotes. Members of this family are known as canines.

cancer Any of more than 100 different diseases, each characterized by the rapid, uncontrolled growth of abnormal cells. The development and growth of cancers, also known as malignancies, can lead to tumors, pain and death.

cell The smallest structural and functional unit of an organism. Typically too small to see with the naked eye, it consists of watery fluid surrounded by a membrane or wall. Animals are made of anywhere from thousands to trillions of cells, depending on their size.

diabetes A disease where the body either makes too little of the hormone insulin (known as type 1 disease) or ignores the presence of too much insulin when it is present (known as type 2 diabetes).

DNA (short for deoxyribonucleic acid) A long, double-stranded and spiral-shaped molecule inside most living cells that carries genetic instructions. In all living things, from plants and animals to microbes, these instructions tell cells which molecules to make.

domestic animal A tame animal that commonly lives with people, such as a dog, cat or horse.

dynamic An adjective that signifies something is active, changing or moving. (noun) The change or range of variability seen or measured within something.

environment The sum of all of the things that exist around some organism or the process and the condition those things create for that organism or process. Environment may refer to the weather and ecosystem in which some animal lives, or, perhaps, the temperature, humidity and placement of components in some electronics system or product.

epidemiologist Like health detectives, these researchers figure out what causes a particular illness and how to limit its spread.

evolution A process by which species undergo changes over time, usually through genetic variation and natural selection. These changes usually result in a new type of organism better suited for its environment than the earlier type. The newer type is not necessarily more “advanced,” just better adapted to the conditions in which it developed.

gene (adj. genetic) A segment of DNA that codes, or holds instructions, for producing a protein. Offspring inherit genes from their parents. Genes influence how an organism looks and behaves.

genetic Having to do with chromosomes, DNA and the genes contained within DNA. The field of science dealing with these biological instructions is known as genetics. People who work in this field are geneticists.

genome The complete set of genes or genetic material in a cell or an organism. The study of this genetic inheritance housed within cells is known as genomics.

immune system The collection of cells and their responses that help the body fight off infections and deal with foreign substances that may provoke allergies.

mammal A warm-blooded animal distinguished by the possession of hair or fur, the secretion of milk by females for feeding the young, and (typically) the bearing of live young.

meningitis A potentially deadly bacterial infection that affects the protective membranes, known as meninges, that cover the brain and spinal cord. Symptoms may include a sudden fever, headache and stiff neck. Vomiting, sensitivity to light and confusion may also develop.

mutation Some change that occurs to a gene in an organism’s DNA. Some mutations occur naturally. Others can be triggered by outside factors, such as pollution, radiation, medicines or something in the diet. A gene with this change is referred to as a mutant.

National Cancer Institute The largest of the 21 institutes making up the National Institutes of Health. With a staff of almost 4,000 people, NCI is based in Bethesda, Md. It’s budget of almost $5 billion a year goes to support research — by its scientists and outside researchers — to better understand, diagnose and treat cancers.

ophthalmologists Physicians who specialize in the eye. They begin as general medical doctors and then get several additional years of training on diagnoses and treatment of problems affecting the eyes. Optometrists, in contrast, are doctors but are not trained as physicians (what in the United States are known as “medical” doctors).

Pallas’s cat A small wild cat native to Central Asia.

PhD (also known as a doctorate) A type of advanced degree offered by universities — typically after five or six years of study — for work that creates new knowledge. People qualify to begin this type of graduate study only after having first completed a college degree (a program that typically takes four years of study).

postdoctoral scholar (or post-doc) A research position for people who have just completed their doctorate in some field of study. It allows the individual to acquire new skills or pursue new lines of research on the road to a research career.

psychology The study of the human mind, especially in relation to actions and behavior. To do this, some perform research using animals. Scientists Scientists and mental-health professionals who work in this field are known as psychologists.

reptile A cold-blooded vertebrate animal whose skin is covered with scales or horny plates. Snakes, turtles, lizards and alligators are all reptiles.

rodent A mammal of the order Rodentia, a group that includes mice, rats, squirrels, guinea pigs, hamsters and porcupines.

Salmonella A genus of bacteria that can cause disease in people and animals.

salmonellosis An infection caused by Salmonella bacteria that causes abdominal cramps and diarrhea. For young children, the elderly and people with weakened immune systems, the disease can be serious and even deadly.

sequencing Technologies that determine the order of nucleotides or letters in a DNA molecule that spell out an organism’s traits.

species A group of similar organisms capable of producing offspring that can survive and reproduce.

trait A characteristic feature of something. (in genetics) A quality or characteristic that can be inherited.

trump In certain card games, it’s a card that owing to some special feature (such as its suit) allows it to rank above all others. In pinochle, for instance, a 2 of the trump suit can capture even an ace of any other suit. (outside card games) Some feature or action that outperforms or tops all others.

veterinary Having to do with animal health. A doctor who specializes in treating animals is aveterinarian.

virus Tiny infectious particle consisting of RNA or DNA surrounded by protein. Viruses can reproduce only by injecting their genetic material into the cells of living creatures. Although scientists frequently refer to viruses as live or dead, in fact no virus is truly alive. It doesn’t eat like animals do, or make its own food the way plants do. It must hijack the cellular machinery of a living cell in order to survive.

zoonosis (plural: zoonoses) Any disease that originates in nonhuman animals and is later contracted by people. Many zoonotic diseases also spread among a host of non-human species. For instance, the type of swine flu that sickened people throughout the world in 2009 also infected marine mammals, including sea otters.

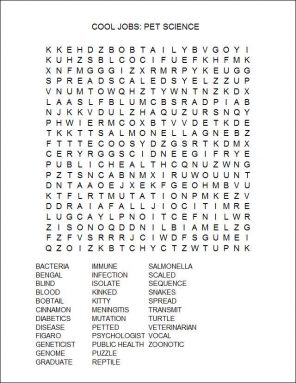

Word Find (click here to enlarge for printing)