No frostbite for dogs

Blood vessels in dog paws keep their temperature just right

Puppy paws keep warm thanks to special blood vessels.

stanzi11/iStockphoto

Share this:

- Share via email (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share to Google Classroom (Opens in new window) Google Classroom

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

When playful pups skid across an icy pond or romp in a snowdrift, their paws plunge into frosty places. If people go barehanded and barefooted in such cold places, their skin may freeze in a painful condition called frostbite. Dogs frolic without fear of frostbite, and scientists from Japan say they’ve figured out why.

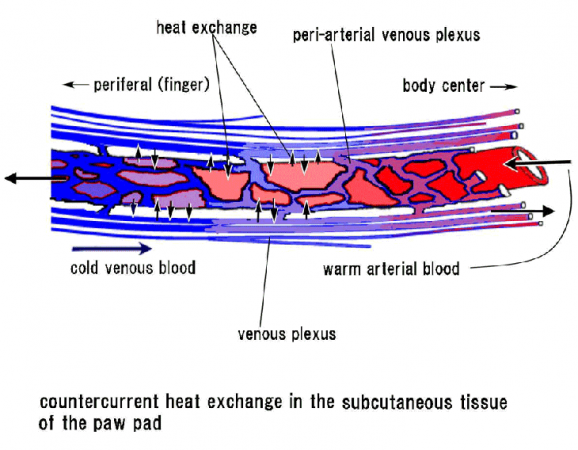

Dog paws don’t freeze because the arrangement of blood vessels beneath the animals’ skin keeps the temperature just right, the scientists report. The arrangement helps the animal hold on to body heat, which might otherwise be easily lost through their hairless paws.

Hiroyoshi Ninomiya, an expert in animal anatomy from Yamazaki Gakuen University in Tokyo, led the new study on dog paws. During summer, hot asphalt in Japan can reach a scorching 66º Celsius (150º Fahrenheit), he notes. In the winter, the same pavement may drop to about –9º C (15º F).

“I have always wondered how a dog’s paw stands up to that wide temperature difference,” Ninomiya says.

He and his colleagues took pictures of blood vessels in beagles’ paws using a tool called a scanning electron microscope, or SEM. This instrument fires a stream of electrons — small particles that are some of the building blocks of atoms — at a target. Then the device measures how the electrons are absorbed, changed or reflected. An SEM gives scientists a view of parts of the natural world that are too tiny to view with ordinary microscopes.

The scientists studied blood vessels called arteries and veins. Arteries carry warm blood from the heart to the rest of the body; veins bring blood back to the heart. The scientists discovered that veins surround the arteries that deliver warm blood to dog paws. The two kinds of blood vessels are so close together that they exchange heat: The warm arteries heat up the cooler veins.

As a result, the temperature in the paw stays balanced. Warm blood reaches the pad’s surface to keep frostbite away, but without letting the animal lose too much body heat.

Scientists call this kind of system a counter-current heat exchanger. Ninomiya and his colleagues are the first researchers to find it in dogs, although it has been observed in other animals. Animals like penguins, whales and seals use counter-current heat exchangers in their feet, fins and flippers to keep their body heat balanced. Ninomiya says that he and his colleagues were excited to find that dog paws have a heating system like penguins.

Blood vessels in the dog paws open and close with changes in temperature, the scientists also found. This allows more or less blood to flow, depending on where it’s needed.

In his previous work, Ninomiya studied blood vessels in birds, rabbit ears and whale eyes. Up next, he says, is a close look at cats’ paws. Domestic dogs are related to many animals that live in cold places and need to regulate heat. Cats, in contrast, originally evolved in a warm climate.

“I want to know whether cats have the counter-current heat exchange mechanism in the paw as seen in the dog,” he says.

This story and other Science News for Kids articles describing research in medicine and physiology are supported with funding from The Lasker Foundation. The foundation and its programs are dedicated to the support of biomedical research toward conquering disease, improving human health and extending life.