Uh oh! Baby fish prefer plastic to real food

This choice changes their behavior — and can lead to their death

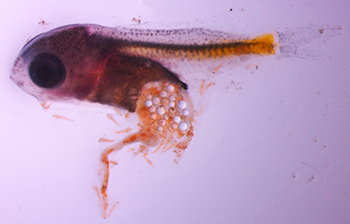

Larval perch with a belly full of tiny plastic beads. The fish preferred this junk food over the nutritious prey on which it usually feeds.

Oona Lönnstedt

Editor’s note: On May 3, 2017, the journal Science retracted the study described in this article. That means the journal no longer stands by the paper and its conclusions. This retraction is based on an investigation at Uppsala University in Sweden (where the authors work) into “allegations of dishonesty in research.” Findings from a review board at that school concluded that data on which the original paper’s findings were based have gone missing (so they cannot be confirmed). In addition, it said that methods described in the article were not those used in the study. Finally, the review committee found “considerable differences between what has been stated by the authors and what has been reported by eyewitnesses when the experiments were conducted.” Retractions, although not common, are one way that the science community attempts to police itself. To learn more about why retractions happen and what they may (or may not) mean, read our Sept. 11, 2015 story Retractions: Righting the wrongs of science.

Let a baby perch choose between a nutritious meal and a piece of plastic, and this little fish will go for the plastic. That’s the disturbing conclusion of a study to be published June 3 in the journal Science.

It’s disturbing because eating plastic stunts the animals’ growth. It also alters the behavior of the baby fish. This new behavior makes them easier for predators to find — and gobble down as lunch.

Researchers aren’t sure why baby perch choose plastic over real food. But their new data might explain why some fish populations are decreasing, says Peter Eklöv. One of the study’s authors, he works at Uppsala University in Sweden. There he probes how predator fish and their prey interact.

“It’s kind of scary what the results show,” says Eklöv. “We really need to do something about this.” His team is now testing species of baby fish other than perch. And early results show these fish, too, prefer plastic over real food.

People have been concerned for some time about rising plastic pollution in oceans and lakes. Sunlight, waves and wind break down plastic into tiny fragments. Plastic lint flows out of washing machines and down the drain. Eventually it can flow into rivers and the sea. Microbeads added to some face cleansers are taking the same path into the environment.

Previous studies showed fish and other aquatic organisms can ingest these tiny bits of plastic. That plastic can then move up the food chain as seabirds, seals and other marine predators eat those fish.

A second risk: Plastic can pick up toxic chemicals. These include PCBs, pesticides and flame retardants. When ingested, plastic can release these pollutants, poisoning the dining predator.

Eggs and hatchlings affected

The Swedish researchers used beads made from polystyrene — a type of plastic used in packaging. Their new study now shows for the first time that baby fish with access to this plastic preferred it to their natural food: zooplankton. Those zooplankton are tiny creatures that drift in the sea and are an important food for small fish.

The Uppsala team started its new research by studying perch. These are a type of freshwater species. They also can live in semi-salty, or brackish, water. One such place is the Baltic Sea.

The zooplankton that baby perch normally eat are the same size as are many of the tiny plastic bits found polluting lakes and oceans around the world.

Eklöv and Oona Lönnstedt, a marine biologist, collected perch eggs from the Baltic Sea. They put roughly equal numbers of them in three fish tanks containing zooplankton.

Into two tanks, the researchers added tiny polystyrene beads. They added low levels to one tank. The concentration was equal to what has been seen in some coastal ocean waters. A second tank got far higher levels of the beads. The last tank got no plastic.

Almost all of the eggs — 96 percent — hatched in the tank free of plastic. That rate is normal. In the tank with low level of plastic beads, 89 percent of the eggs hatched. In the tank with high levels of plastic beads, only 81 percent hatched.

Growth and behavior impaired in survivors

Hatchlings in the tank with no plastic grew normally. Those in the tanks containing plastic did not.

Larval fish growing in water with the low level of plastic beads grew at a slow rate. Those exposed to higher levels of the plastic grew more slowly still.

Unless, that is, a predator fish eats them first.

In a second experiment, Eklöv and Lönnstedt added a chemical to each fish tank. It smelled like a pike, a fish that eats baby perch. Perch know when a pike is nearby based on this scent.

Baby perch raised in water free of the plastic reacted normally to the pike scent. Their movements froze. These fish didn’t want to risk attracting attention.

Perch exposed to the lower level of plastic were less likely to freeze. Those exposed to high levels of polystyrene beads did not alter their movements at all. They swam normally.

Next, the researchers put real pike in the tanks with the baby fish. Almost half of the perch that had been raised in plastic-free water were still alive after 24 hours. That was considered normal.

Fish reared with the low levels of plastic weren’t so lucky. Fewer than one-third lasted 24 hours before being eaten. Fish exposed to the high level of plastic were all goners. None survived 24 hours before being gobbled up by the pike.

The researchers aren’t sure how plastic affects a fish’s ability to pick up the scent of predators. But they know the result is deadly.

Chelsea Rochman is an aquatic ecologist at University of Toronto in Canada. She says scientists know without a doubt that small pieces of plastic are littered across the planet. But they know very little about their impacts on wildlife.

“This study provides some of the first demonstrated evidence of impacts that are relevant to nature,” she says. “They show that microplastic [tiny plastic] debris decrease the ability for a fish to hatch from its egg.” That means it will not survive, she adds.

The new data “also show a decrease in the ability of fish to escape a predator,” she points out. And that, she notes, “can ultimately reduce the size of the fish population.”