Students use STEM to help their community

Finalists show off science-based designs to solve local problems

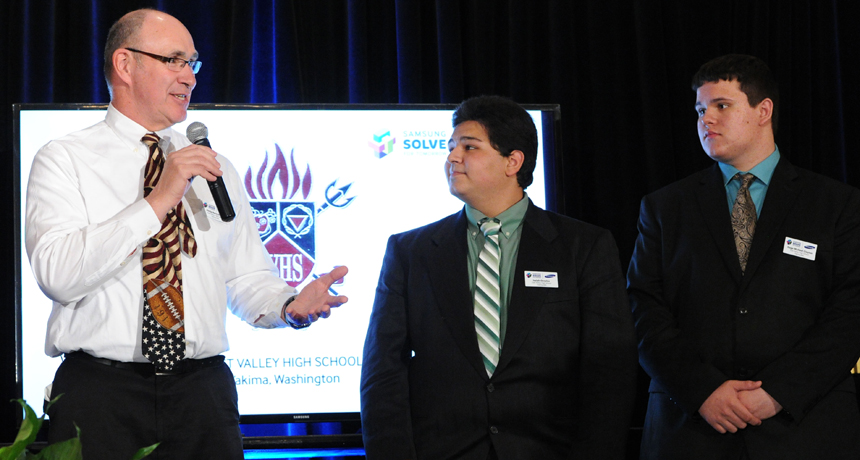

Barry Reifel, a technology teacher at East Valley High School in Yakima, Wash., presents his classroom’s room-cooling solution with students Isaiah Ornelas, 17, and Gage Clayton, 15.

Samsung

As we walk around our communities, it’s easy to see problems that need fixing. Maybe there are signs of crime. Maybe we see air conditioning units running and realize just how much energy we use every day. Or maybe we worry about the impacts of floating plastic bottles on the ducks beside them in our favorite pond.

Many of us will just go about our daily lives trying to ignore these problems. But this year, middle-school and high-school classrooms across the United States tackled such local problems head on. As part of the fourth annual Samsung Solve for Tomorrow contest, 51 classrooms (one from each state and the District of Columbia) applied their knowledge of science, technology, engineering and math to solve everyday problems in their communities.

“One of the things I see as I look at the contest applications,” says David Steel, “is the incredible diversity of local problems to which you can apply STEM solutions.” He’s an executive vice president for the Samsung North America office in Ridgefield Park, N.J. This year’s finalists investigated everything from keeping their town cool to finding a low-crime route to school. The top 5 classrooms received more than $140,000 each in technology equipment to be used by classrooms in their schools.

“I was just looking at the sewer grates and I thought, ‘There has to be a better way,’” says James Intrabartolo. He is a middle-school science teacher at Oliver Street School in Newark, N.J. Last September, he sent in one of the 2,300 applications for the 2014 Solve for Tomorrow contest. When his classroom made the first cut in November as one of 255 state semifinalists (five per state), he drafted a detailed lesson plan to explain how his class would learn about problem solving through a focus on the local sewer system. His and 50 other projects got underway in December when their classes were named as national finalists. Each team was asked to design a solution to some problem, and to make a video demonstrating their result.

Intrabartolo’s class worked on designing a better street drain. It filters out trash before the storm runoff flows into the rivers and streams near their school. “First we brainstormed and sketched on paper. Finally we built a prototype with the best design,” explains Gabriel Margaca. Gabriel, 12, designed the top-performing filter. It’s a narrow, rectangular metal bucket that fits into a storm drain. Water flows into the bucket and out through holes on the sides and bottom. The holes allow water through while trapping trash inside. A filter is braced inside the storm drain, and slides out for easy cleaning.

The Oliver Street School project was selected as one of the contest’s top 15 national finalists. The classrooms responsible received a free trip for two students and their teacher to the South by Southwest Education meeting in Austin, Texas. There, a panel of judges selected the five winning projects — including the new storm-drain filter.

While the students were happy to win technology for their school, they were more excited by improving their community. “Their dream,” says Intrabartolo, “is to walk down the street and see their filter in a drain someday.”

The students in an engineering class at East Valley High School in Yakima, Wash., were concerned with how much power was being sucked up by air conditioning in their town. A traditional window unit eats up 1,100 watts per hour to cool a single room. When the students multiplied that number by the more than 33,000 homes in their town, they were shocked.

Their solution was to develop HydroChill. This simple machine runs water through a car’s radiator. A household box fan stands behind the car radiator and blows air from the outside over the running water. “Whenever warm air passes through the cool water it trades temperatures,” explains Isaiah Ornelas, 17. His classroom’s HydroChill unit can cool a room almost as well as an air conditioner, yet sips a mere 92 watts per hour. That’s only about as much power as a big incandescent light bulb. Isaiah says that the experience helped him realize “our own ideas can help the environment.”

The contest is open to sixth- through twelfth-grade classrooms. Teachers can complete the online application beginning in September.

Follow Eureka! Lab on Twitter

Editor’s Note: This post was updated May 7, 2014, to correct the title of David Steel and the location of Samsung.