Think you’re not biased? Think again

Everyone has unconscious biases about certain social groups — but there are ways to limit them

Data show that most Americans have a pro-white, anti-black bias — even when they don’t think they do.

monkeybusinessimages/iStockphoto

A little misbehavior at school can land kids in hot water. How much? In many cases, that depends on the color of a student’s skin. Black students more frequently get detention for being disruptive or loud. White students acting the same way are more likely to get off with a warning.

That doesn’t mean that teachers and administrators are racist. At least, most don’t intend to be unfair. Most want what’s best for all students, no matter what their race or ethnicity might be. And they usually believe that they treat all students equally.

But all people harbor beliefs and attitudes about groups of people based on their race or ethnicity, gender, body weight and other traits. Those beliefs and attitudes about social groups are known as biases. Biases are beliefs that are not founded by known facts about someone or about a particular group of individuals. For example, one common bias is that women are weak (despite many being very strong). Another is that blacks are dishonest (when most aren’t). Another is that obese people are lazy (when their weight may be due to any of a range of factors, including disease).

People often are not aware of their biases. That’s called an unconscious or implicit bias. And such implicit biases influence our decisions whether or not we mean for them to do so.

Having implicit biases doesn’t make someone good or not-so-good, says Cheryl Staats. She’s a race and ethnicity researcher at Ohio State University in Columbus. Rather, biases develop partly as our brains try to make sense of the world.

Our brains process 11 million bits of information every second. (A bit is a measure of information. The term is typically used for computers.) But we can only consciously process 16 to 40 bits. For every bit that we’re aware of, then, our brains are dealing with hundreds of thousands more behind the scenes. In other words, the vast majority of the work that our brains do is unconscious. For example, when a person notices a car stopping at a crosswalk, that person probably notices the car but is not consciously aware of the wind blowing, birds singing or other things happening nearby.

To help us quickly crunch through all that information, our brains look for shortcuts. One way to do this is to sort things into categories. A dog might be categorized as an animal. It might also be categorized as cuddly or dangerous, depending on the observers’ experiences or even stories that they have heard.

As a result, people’s minds wind up lumping different concepts together. For example, they might link the concept of “dog” with a sense of “good” or “bad.” That quick-and-dirty brain processing speeds up thinking so we can react more quickly. But it also can allow unfair biases to take root.

“Implicit biases develop over the course of one’s lifetime through exposure to messages,” Staats says. Those messages can be direct, such as when someone makes a sexist or racist comment during a family dinner. Or they can be indirect — stereotypes that we pick up from watching TV, movies or other media. Our own experiences will add to our biases.

The good news is that people can learn to recognize their implicit biases by taking a simple online test. Later, there are steps people can take to overcome their biases.

Can people be ‘colorblind’?

“People say that they don’t ‘see’ color, gender or other social categories,” says Amy Hillard. However, she notes, they’re mistaken. Hillard is a psychologist at Adrian College in Michigan. Studies support the idea that people can’t be truly “blind” to minority groups, she notes. Everyone’s brain automatically makes note of what social groups other people are part of. And it takes only minor cues for our minds to call up, or activate, cultural stereotypes about those groups. Those cues may be a person’s gender or skin color. Even something as simple as a person’s name can trigger stereotypes, Hillard says. This is true even in people who say they believe all people are equal.

Many people are not aware that stereotypes can spring to mind automatically, Hillard explains. When they don’t know, they are more likely to let those stereotypes guide their behaviors. What’s more, when people try to pretend that everyone is the same — to act as though they don’t have biases — it doesn’t work. Those efforts usually backfire. Instead of treating people more equally, people fall back even more strongly onto their implicit biases.

Race is one big area in which people may exhibit bias. Some people are explicitly biased against black people. That means they are knowingly racist. Most people are not. But even judges who dedicate their lives to being fair can show implicit bias against blacks. They have tended, for instance, to hand down harsher sentences to black men than to white men committing the same crime, research has shown.

And whites aren’t the only people who have a bias against blacks. Black people do, too — and not just in terms of punishment.

Consider this 2016 study: It found teachers expect white students to do better than black ones. Seth Gershenson is an education policy researcher at American University in Washington, D.C. He was part of a team that studied more than 8,000 students and two teachers of each of those students.

They looked at whether the teacher and student were the same race. And about one in every 16 white students had a non-white teacher. Six in every 16 black students had a teacher who was not black. Gershenson then asked whether the teachers expected their students to go to — and graduate from — college.

White teachers had much lower expectations for black students than black teachers did. White teachers said they thought a black student had a one-in-three chance of graduating from college, on average. Black teachers of those same students gave a much higher estimate; they thought nearly half might graduate. In comparison, nearly six in 10 teachers — both black and white — expected white students to complete a college degree, Gershenson says. In short, both sets of teachers showed some bias.

“We find that white teachers are significantly more biased than black teachers,” he notes. Yet the teachers were not aware they were biased in this way.

Does gender matter?

Implicit bias is a problem for women, as well. Take, for instance, the unfounded claim that women aren’t good at science, technology, engineering or math (STEM). Women can (and frequently do) excel in all of these areas. In fact, women earn 42 percent of science and engineering PhDs. Yet only 28 percent of people who get jobs in STEM fields are women. And women who do work in STEM tend to earn less than do men of equal rank. They also receive fewer honors and are promoted less frequently than the men they work with.

This gender difference in hiring and promotion may be due partly to a bias in how recommendation letters are written. Such letters help employers know how well a person has done in a past job.

In one 2016 study, researchers at Columbia University in New York City probed what was said in those recommendations. The team examined 1,224 letters of recommendation written by professors in 54 different countries. Around the world, both men and women were more likely to describe male students as “excellent” or “brilliant.” In contrast, letters written for female students described them as “highly intelligent” or “very knowledgeable.” Unlike the terms used for men, these phrases do not set women apart from their competition, the researchers say.

Biases against women don’t only happen in the sciences. Research by Cecilia Hyunjung Mo finds that people are biased against women in leadership positions, too. Mo is a political scientist at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn.

Women make up 51 percent of the U.S. population. Yet they make up only 20 percent of people serving in the U.S. Congress. That’s a big difference. One reason for the gap may be that fewer women than men run for political office. But there’s more to it, Mo finds.

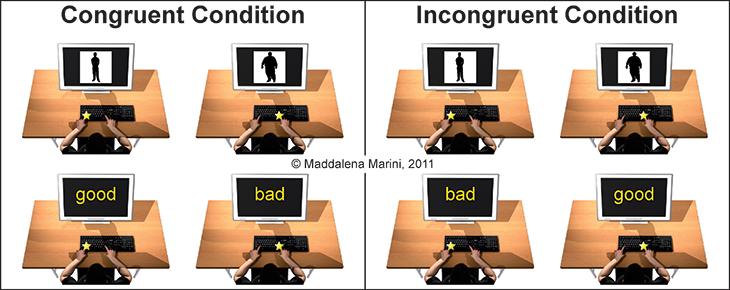

In one 2014 study, she asked 407 men and women to take a computerized test of implicit bias. It’s called the implicit association test, or IAT. This test measures how strongly people link certain concepts, such as “man” or “woman,” with stereotypes, such as “executive” or “assistant.”

During the test, people are asked to quickly sort words or pictures into categories. They sort the items by pressing two computer keys, one with their left hand and one with their right. For Mo’s test, participants had to press the correct key each time they saw a photo of a man or a woman. They had to choose from the same two keys each time they saw words having to do with leaders versus followers. Halfway through the tests, the researchers switched which concepts were paired together on the same key on the keyboard.

Story continues below video.

Vanderbilt University

People tended to respond faster when photos of men and words having to do with leadership shared the same key, Mo found. When photos of women and leadership-related words were paired together, it took most people longer to respond. “People typically found it easier to pair words like ‘president,’ ‘governor’ and ‘executive’ with males, and words like ‘secretary,’ ‘assistant’ and ‘aide’ with females,” Mo says. “Many people had a lot more difficulty associating women with leadership.” It wasn’t only men who had trouble making that association. Women struggled, too.

Mo also wanted to know how those implicit biases might be related to how people behave. So she asked the study participants to vote for fictional candidates for a political office.

She gave each participant information about the candidates. In some, the male candidate and the female candidate were equally qualified for the position. In others, one candidate was more qualified than the other. Mo’s results showed that people’s implicit biases were linked to their voting behavior. People who showed stronger bias against women in the IAT were more likely to vote for the male candidate — even when the woman was better qualified.

Story continues below image.

Size matters

One of the strongest social biases is against the obese. Chances are, you harbor a dislike for people who are severely overweight, says Maddalena Marini. She is a psychologist at Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass. Implicit weight bias seems universal, she says. “Everyone possesses it. Even people who are overweight or obese.”

To reach that conclusion, she and her team used data from Harvard’s Project Implicit website. This site allows people to take an IAT. There are currently 13 types of these tests of implicit bias on the site. Each probes for a different type of bias. More than 338,000 people from around the world completed the weight-bias test between May 2006 and October 2010, the time leading up to Marini’s study. This IAT was similar to the one for race. But it asked participants to categorize words and images that are associated with good and bad, and with thin and fat.

After taking the IAT, participants answered questions about their body mass index. This is a measure used to characterize whether someone is at a healthy weight.

Story continues below image.

Marini found that heavier people have less bias against people who are overweight or obese. “But they still prefer thin people, on average,” she notes. They just don’t feel this way as strongly as thin people do. “Overweight and obese people tend to identify with and prefer their weight group,” Marini says. But they may be influenced by negativity at the national level that leads them to prefer thin people.

People from 71 nations took part in the study. That allowed Marini to examine whether an implicit bias against heavy people was linked in any way to whether weight problems were more common in their nation. To do this, she combed public databases for weight measurements from each country. And nations with high levels of obesity had the strongest bias against the obese, she found.

She’s not sure why obese nations have such a strong implicit bias against overweight people. It could be because those nations have more discussions about the health problems associated with obesity, Marini says. It may also come from people seeing more ads for “diet plans, healthy foods and gym memberships aimed at decreasing obesity,” she notes. Or perhaps people in these countries simply see that people with high social status, good health and beauty tend to be thin.

Weight bias seems to be more commonly accepted than race and gender bias. In other words, people tend to feel freer to verbally express their weight bias. That’s according to a 2013 study led by Sean Phelan. He is a policy researcher at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. Medical students often express weight bias openly, he finds. And that can translate into poorer health care for people who are severely overweight. “Health-care providers display less respect for obese patients,” he reports. He also notes that research shows that “physicians spend less time educating obese patients about their health” than they do with patients who aren’t obese.

Embracing diversity breaks down bias

Antonya Gonzalez is a psychologist in Canada at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. “We may think we treat everyone equally,” she says, but “unconscious biases can shape our behavior in ways we aren’t always aware of.” Knowing that you might be biased “is the first step to understanding how you treat other people — and trying to change your own behavior,” she says.

Gonzalez knows about changing behavior. In a 2016 study with 5- to 12-year-old children, she found that their implicit bias against black people could change. The children were told positive stories about people, such as a firefighter who works hard to protect his community. Some children saw a photo of a white man or woman while they heard the story. Others saw a photo of a black person. After the story, each child took a race IAT. Children who learned about a black person were less biased when they took the test, compared with children who had heard about a white person.

“Learning about people from different social groups who engage in positive behaviors can help you to unconsciously associate that group with positivity,” Gonzalez says. “That’s part of the reason why diversity in the media is so essential,” she notes. It helps us to “learn about people who defy traditional stereotypes.”

Hillard at Adrian College also found that diversity training can help adults counteract a bias against women. “The first step is awareness,” she says. Once we are aware of our biases, we can take steps to block them.

It also helps to step back and think about whether stereotypes could possibly provide good information to act on, she notes. Could a stereotype that is supposed to be true of a large portion of the population, such as “all women” or “all people of color,” truly be accurate?

The key is to embrace diversity, says Staats — not to pretend it doesn’t exist. One of the best ways to do this is to spend time with people who are different than you. That will help you see them as individuals, rather than part of a stereotypical group.

“The good news is that our brains are malleable,” she says. “We are able to change our associations.”