Is Zealandia a continent?

Landmass lies mostly beneath the Pacific Ocean

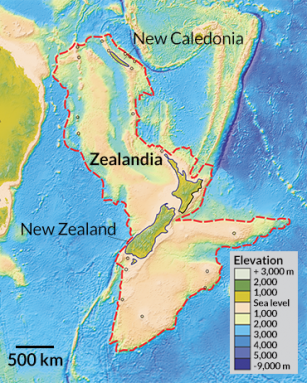

New Zealand rises from the center of a previously unknown, largely submerged continent, scientists propose. They call it Zealandia.

Stuart Rankin/Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0), NASA

Lurking beneath New Zealand is a long-hidden continent, geologists now propose. They call it Zealandia. Don’t expect it to soon end up on a map on your classroom wall, though. Nobody is in charge of officially designating a new continent. Scientists will have to judge for themselves if Zealandia should be added to the ranks of continents.

A team of geologists pitched the scientific case for judging this a new continent in the March/April issue of GSA Today. Zealandia is a continuous expanse of continental crust. It covers some 4.9 million square kilometers (1.9 million square miles). That’s about the size of the Indian subcontinent. But it would be the smallest of the world’s continents. And unlike the others, around 94 percent of Zealandia hides beneath the ocean. Only New Zealand, New Caledonia and a few small islands peek above the waves over it.

“If we could pull the plug on the world’s oceans, it would be quite clear that Zealandia stands out,” says study coauthor Nick Mortimer. He is a geologist at GNS Science in Dunedin, New Zealand. Zealandia rises about 3,000 meters (9,800 feet) above the surrounding ocean crust, he notes. “If it wasn’t for the ocean level,” he says, “long ago we’d have recognized Zealandia for what it was — a continent.”

Story continues below map

This landmass, directly east of Australia, will face an uphill battle for continent status. New planets and slices of geologic time have international panels that can officially name them. But there is no such group to officially validate new continents. The current number of continents is already vague. Most everyone agrees on five of them: Africa, Antarctica, Australia and North and South America. Some people, however, combine the last two — Europe and Asia — into one huge Eurasia. There’s no formal way to add Zealandia to this mix. Proponents will just have to start using the term and hope it catches on, Mortimer says.

This odd path forward stems from the simple fact that nobody expected another continent would ever need to be added, says Keith Klepeis. He is a structural geologist at the University of Vermont in Burlington. He supports the move to add Zealandia. Its discovery illustrates that “the large and obvious can be overlooked in science,” he says.

A case for a new continent

Earth is composed of three main layers — a core, mantle and crust. The crust comes in two types. Continental crust is made of rocks such as granite. A much denser ocean crust is made of a volcanic rock known as basalt. Because ocean crust is thinner than continental crust, it doesn’t rise up as far. That has created low spots around the globe that have been filled in by oceans.

Continents can’t be made of oceanic crust. But having continental crust isn’t enough to confirm Zealandia is a new continent. For a decade, Mortimer and others have been building a case that it is. They have now ticked off all of the boxes that they believe are required. For instance, the region is composed of continental rocks such as granite. The region also is distinct from nearby Australia. (That is thanks to an intervening stretch of ocean crust.)

“If Zealandia was physically attached to Australia, then the big news story here wouldn’t be that there’s a new continent on planet Earth,” Mortimer says. “It’d be that the Australian continent is 4.9 million square kilometers larger.”

There are other geologic features that rise from the seafloor. These can include volcano-built submarine plateaus. But they either are not made of continental crust or are not distinct from nearby continents. (That’s an argument for why Greenland would not be a continent).

Size might prove a sticking point, however. No minimum size requirement exists for continents. (Both submerged and dry areas contribute to a continent’s overall size.) Mortimer and his colleagues propose a 1-million-square-kilometer (0.4-million-square-mile) minimum. If this lower size limit is accepted, Zealandia would become the scrawniest continent by far. It is just a little more than three-fifths the size of Australia.

Scientists dub smaller fragments of continental crust as “microcontinents.” Those that are attached to larger continents are subcontinents. Madagascar is one of the larger microcontinents. Zealandia is about six times larger. That means it fits better as a continent than a microcontinent, Mortimer and his colleagues maintain.

“Zealandia’s in this sort of gray zone,” says Richard Ernst. He is a geologist at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada. He proposes that an intermediate term could help bridge the gap between microcontinent and full-blown continent. He suggests that it be called a mini-continent. That definition would cover Zealandia. It also would cover other not-quite-continents such as India before it plowed into Eurasia tens of millions of years ago. Such a solution would be similar to the route taken for Pluto. It was demoted from planet to the newly coined “dwarf planet” status in 2006.

Scientists previously assumed that New Zealand and its neighbors were an assortment of islands — fragments of long-gone continents and other geologic odds and ends. Recognizing Zealandia as a coherent continent would help scientists piece together ancient supercontinents, Mortimer says. It also could aid in the study of how geologic forces reshape landmasses over time.

Zealandia probably began as part of the southeastern edge of the supercontinent Gondwana before it began peeling off around 100 million years ago. This breakup stretched, thinned and distorted Zealandia, which ultimately lowered the region below sea level.