Student programs computer to predict path of space trash

Her computer program predicts where this litter will end up

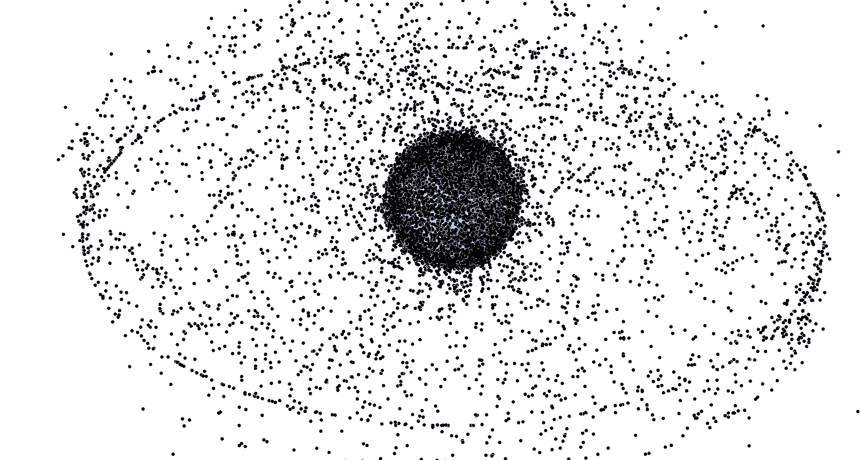

Not many people have been to space, but that hasn't kept our species from littering our space environment. This illustration represents all the objects currently being tracked in high Earth orbit.

NASA illustration courtesy Orbital Debris Program Office

WASHINGTON, D.C. — People are messy. We’re so messy we’ve even left trash in space, where it can be a danger to satellites and astronauts. Amber Yang, 17, wanted to forecast where this trash might travel. The computer program she created can predict where space debris might go next. It might even, one day, help space travelers stay avoid space trash crashes.

The senior at Trinity Preparatory School in Winter Park, Fla., presented her program at the Regeneron Science Talent Search. This yearly competition was created by Society for Science & the Public and is sponsored by Regeneron, a company that develops medications. The event brings together 40 high school seniors from around the country. Here, they show off their science projects to the public and compete for almost $2 million in prizes. (Society for Science & the Public also publishes Science News for Students and this blog.)

Already, more than 500,000 pieces of space trash orbit Earth. They come from old satellites and other objects humans have sent into space. Each travel at more than 28,000 kilometers (17,500 miles) per hour. At speeds like that, even tiny flecks of dust can harm spacecraft — and any passengers.

Growing up near Kennedy Space Center in Florida, Amber has always been interested in space. But she didn’t think about space junk until 2013. That year, debris from an old Chinese satellite — destroyed in 2007 — collided with an active Russian satellite. The space trash slammed into the satellite, knocking it off course and out of commission.

Space agencies try to keep track of space junk and where it’s going. But Amber decided to come up with her own method — one that could use the knowledge of where space junk has been to more accurately predict where it would go next. She used her computer to create an artificial neural network. This is a computer program that works somewhat like the human brain. “It learns from past mistakes and recognizes patterns,” she explains.

To find out where space junk might travel, Amber started with a set of rules called Kepler’s laws of planetary motion. Johannes Kepler developed these rules in the 1600s. They describe how planets and other objects — of any size — move through space. Scientists can use these laws to figure out where objects in space are traveling.

Amber’s computer program applied Kepler’s laws to data on the locations of space trash. She hoped her artificial neural network could use those data to figure out where that junk could go next. If those predictions turned out to be wrong, her program could learn from those mistakes to do better in the future.

“When I first started out with my research,” Amber says, “I had a hard time finding data for space debris.” So she randomly generated her own data. The next year, though, Amber discovered space-track.org. This website provides a free record of space debris. It let Amber use real data to test her program.

She downloaded data on the locations of space debris for May 25 to June 9, 2016. She then asked her program to use those data to predict where the trash would be on June 12. She compared her program’s answer to the actual locations of the space trash. “I had 98 percent accuracy,” she says.

Amber hopes to take her enthusiasm for space and one day start her own company.

Research gave the teen a sense of excitement she hadn’t felt in science class. “Before I started this research, science was presented to me in a strict, boring way in school,” she recalls. “This was the first time I was going out and learning things for myself.” She quickly found that figuring out how to solve problems can be addictive. “I spent my entire Christmas break, junior year, working on this,” she says. “It was the best time of my life.”

Follow Eureka! Lab on Twitter