Some food-packaging pollutants mess with the thyroid

Teens may be most susceptible to this chemical, which affects hormones

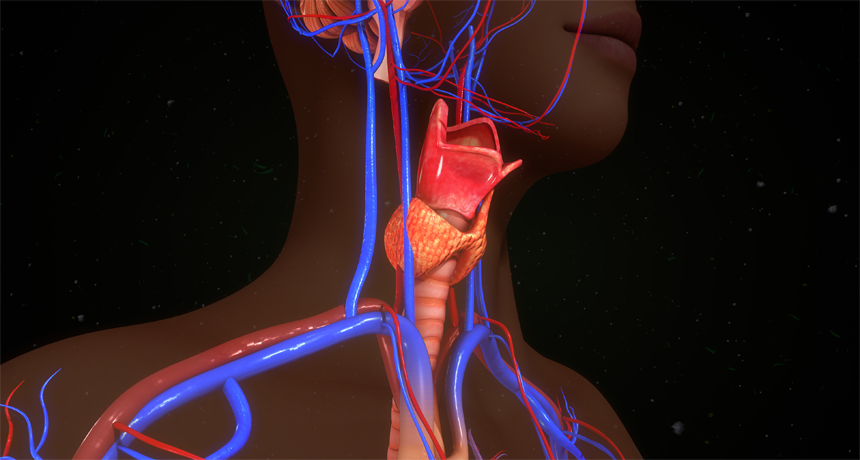

The thyroid is a butterfly-shaped gland in the neck. It makes hormones that help with growth and development.

7activestudio/iStockphoto

There’s a butterfly-shaped gland in your neck that makes hormones — chemicals that signal when certain cells of the body should turn on. One hormone made by this thyroid gland directs several key body processes. These include brain development, bone strength and growth. The hormone even helps to control appetite and weight gain. But certain pollutants can interfere with the production of this hormone. And a new study finds that teens are particularly sensitive to the effects of one of these pollutants.

Called perchlorate (Pur-KLOR-ayt), this chemical is used to make explosives, fireworks and rocket motors. The solid booster rocket on the space shuttle, for instance, contained a lot of perchlorate. Manufacturers also add the chemical to some food packaging. Why? Perchlorate controls static electricity. So spraying it onto paper, cardboard and plastic containers can keep crumbs and bits of food from clinging.

The problem is that some of that perchlorate can rub off. And it can get into the food we eat, explains Tom Zoeller. He works at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst. There he studies how chemicals can block the production or action of thyroid hormones. He wasn’t involved in the new research.

Hormones are major players in the body’s endocrine (EN-doh-krin) system. But pollutants can mess with them. Because of that, such pollutant chemicals are known as endocrine disruptors. They can cause problems in people and animals.

“It’s hard to find a bodily function that isn’t influenced by thyroid hormone,” says Leonardo Trasande. He’s a pediatrician at New York University in New York City. He studies how pollution in the environment can affect a child’s health.

Past research had suggested that in people, perchlorate might be linked to lower-than-normal levels of the thyroid hormone known as thyroxine (Thy-ROX-een). So Trasande led a group of researchers to see if his team could predict a person’s tthyroxine levels based on how much perchlorate was in their body.

And they could, they reported April 20 in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. What’s more, their data show for the first time that teens may be especially vulnerable to the pollutant’s effects.

What they did

Trasande’s team had a hunch perchlorate could mess with the thyroid. That’s because the chemical blocks this gland’s uptake of iodine. This chemical element is an important component of a healthy diet. It occurs naturally in some foods. Iodine is also added to table salt. That’s fortunate, because without it the thyroid cannot make thyroxine.

To probe a possible link between perchlorate and thyroxine, the researchers analyzed urine samples. How much of the pollutant is found in a person’s pee can give scientists a measure of their exposure to perchlorate. The urine came from more than 3,000 people across the United States, all between 12 and 80 years old. The researchers compared the perchlorate levels of urine to the amount of thyroxine in each person’s blood.

The researchers also measured two other chemicals that can block the body’s use of iodine. These were thiocyanate (THY-oh-SY-uh-nayt) and nitrate. Cigarette smoke contains high amounts of thiocyanate. Nitrate is in many plant fertilizers. Each of these chemicals can enter the body through air, water or food.

People exposed to the most perchlorate had about 4 percent less thyroxine in their blood than did people exposed to the least perchlorate. Adolescent girls who were exposed to the most perchlorate saw an even bigger thyroid hormone drop. They had about 8 percent less thyroxine than did people with low perchlorate exposures.

That’s important because people between the ages of 12 and 21 showed the highest exposure to perchlorate. The researchers don’t know why. It might simply be that growing kids eat a lot. “We know adolescents eat more food per body weight than adults,” says Trasande. And, he adds, “Food contamination is a major route of exposure.”

The researchers didn’t measure perchlorate in foods for this study. They also didn’t survey what each of the recruits typically ate. That may be part of some follow-up work.

What it means

Trasande calls his team’s new findings “concerning.” Puberty is a really important period of growth and development.

And, adds Zoeller, “The human body is especially vulnerable to hormonal disruption during periods of rapid change.” Puberty is one of those periods. Kids typically experience their final growth spurt at this time. It’s also when their reproductive organs mature. At the same time, their brains are rewiring themselves to an adult configuration. Thyroxine plays a role in all of these processes.

It’s not clear what the new perchlorate findings mean for thyroid health, says Zoeller. “We don’t know if teens with lower thyroid-hormone levels experience any kind of negative long-term health impacts.”

That’s why he argues that more research and longer-term studies are needed. Researchers need to better understand the relationship between levels of thyroxine and health in pre-teens and teens.

Until then, there are steps teens can take to limit any effects of perchlorate.

They should make sure their diet contains iodine, says Zoeller. Getting enough of it may help counter any iodine-blocking effects of perchlorate and other chemicals. Seafood, dairy products and eggs contain a lot of iodine. Iodized salt — table salt treated with added iodine — does too.

Finally, avoiding packaged foods when possible might also help reduce perchlorate exposures, says Trasande. Indeed, he says, “It may be one more good reason to maintain a healthy diet full of fresh and non-processed foods.”