Plastic trash rides ocean currents to the Arctic

Scientists track tiny pieces of trash at the top of the world

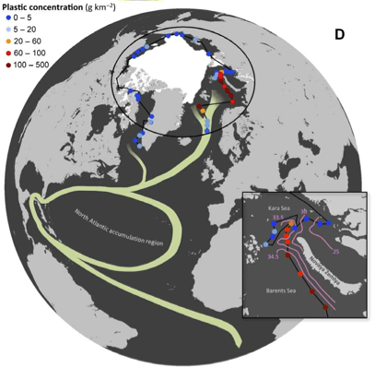

Ocean currents carry trash from North America and western Europe up to the Arctic.

ChepeNicoli

Remember the last plastic straw you used? It may have simply ended up in a landfill. But there’s also a good chance that straw just began a very long journey. Maybe it tumbled out of a garbage truck, for example. The wind might have blown it to a site where rainwater washed it into some stream. Eventually, it might have floated down to the ocean. If that straw hitched a ride on an ocean current, it might have kept traveling. A new study finds that ocean currents send a surprising amount of plastic trash from the North Atlantic up into the Arctic.

And because plastic doesn’t readily break down in the environment, it can stick around long enough to cause trouble. Animals can get tangled in plastic netting or bags. Some critters may mistake it for food and eat it. From tiny plankton to the fish on our plates to sea birds and even whales, plastic increasingly has been finding its way onto the dinner menu of creatures around the world.

Andrés Cózar wanted to know just how far plastic waste travels — and where most of it ends up. Cózar is an oceanographer at the University of Cádiz in Puerto Real, Spain. He worked with scientists from eight different countries for his new study. The team spent five months traveling by boat around the Arctic Ocean.

They motored between Greenland and Norway, along the northern coast of Russia, past Alaska and Canada, and down into the Labrador Sea between North America and Greenland. Along the way, they collected samples of debris from 42 places in the ocean.

To do this, they dragged a net behind their boat. The researchers placed the net just below the water’s surface and dragged it for 20 minutes at a time as they traveled. Openings in the netting were tiny — between one-third and one-half of a millimeter (0.01 to 0.02 inch). Water could flow through them, but small pieces of plastic — called microplastics — could not.

After each haul of those nets through the water, the researchers cleaned, dried and then weighed the collected debris.

The team expected to find less plastic in remote areas, ones far from where people live. And that proved generally true. Most of the Arctic Ocean, which has few people along its borders, had little accumulation of plastic. But two spots had plenty. One hotspot was in the Greenland Sea, east of Greenland. The other was in the Barents Sea, near Norway and Russia.

“Part of the floating plastic that circulates in the Atlantic Ocean enters these polar seas,” Cózar says. The surrounding land and ice then keep the current from carrying the plastic any farther, he says. The pieces are now trapped. Explains Cózar, “The Greenland and Barents Seas act as a dead end for the floating plastic in the Atlantic Ocean.”

To find out where the plastic came from, the team turned to data from the Global Drifter Program. It uses drifting buoys — or “drifters” — that scientists have released into the world’s oceans. Sensors on these buoys measure water temperature at and below the sea surface. They also measure air pressure, wind speeds and how salty the water is.

Carrying GPS units, the drifters relayed their locations to satellites as the buoys floated with the currents. The location data helped team member Erik van Sebille solve the mystery of where the plastic debris had started its journey. Van Sebille is an oceanographer and climate scientist in England at Imperial College London. He used mathematical calculations to tie the drifters’ locations together. This created a picture of how the currents moved. He then used this information to map out how plastic trash had migrated up to the Arctic.

“We can track this plastic near Greenland and in the Barents Sea directly to the coasts of northwest Europe, the U.K. and the East Coast of the U.S.,” he says. “It is our plastic waste that ends up there.”

His team reported its findings on April 19 in Science Advances.

The researchers only measured floating plastic. Most plastic that enters these regions sinks to the Arctic seafloor. That’s because warm water traveling northward along the East Coast of North America cools as it reaches the Arctic. Water is densest when it’s a little above freezing, at 4º Celsius (39.2º Fahrenheit). Here, it stops flowing and starts to sink in the two regions where the team found lots of plastic. Plastic that the water is carrying collects on the surface, then sinks too.

“The amount of plastic in the Arctic likely will continue to increase,” Cózar says. He suspects that will be true “especially on the seafloor. After all, he notes, sooner or later “the floating plastic sinks to the bottom.”

“It’s an important study,” says Melanie Bergmann, who was not involved in the research. She’s a deep-sea ecologist at the Alfred-Wegener-Institute Center for Polar and Ocean Research in Bremerhaven, Germany. The findings provide new evidence that there are spots in the Arctic where plastic piles up, she says. Researchers studying ice cores have also found extremely high levels of microplastics in Arctic sea ice, she observes. The latest study reveals even more about how our trash travels the globe.