Explainer: All about the calorie

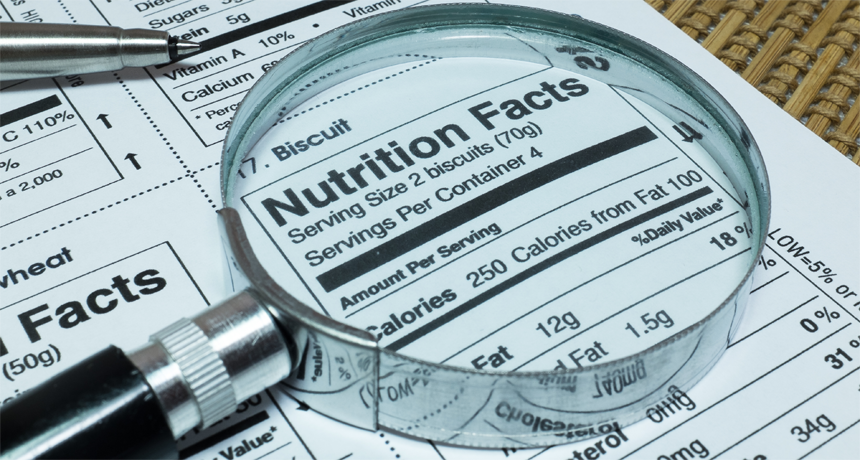

Food labels may not tell the whole story when it comes to understanding how much energy our bodies derive from foods.

chyenchyen/iStockphoto

Calorie counts are everywhere. They appear on restaurant menus, milk cartons and bags of baby carrots. Grocery stores display stacks of foods packaged with bright and colorful “low-calorie” claims. Calories aren’t an ingredient of your food. But they’re key to understanding what you are eating.

A calorie is the measure of stored energy in something — energy that can be released (as heat) when burned. A cup of frozen peas has a very different temperature than a cup of cooked peas. But both should contain the same number of calories (or stored energy).

The term calorie on food labels is short for kilocalorie. A kilocalorie is the amount of energy it takes to raise the temperature of one kilogram (2.2 pounds) of water by 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit).

But what does boiling water have to do with your body’s release of energy from food? After all, your body doesn’t start boiling after eating. It does, however, chemically break down food into sugars. The body then releases the energy pent up in those sugars to fuel processes and activities throughout each hour of the day.

“We burn calories when we’re moving, sleeping or studying for exams,” says David Baer. “We need to replace those calories,” by eating foods or burning up stored fuel (in the form of fats). Baer works at the Beltsville Human Nutrition Research Center in Maryland. It’s part of the Agricultural Research Service. As a physiologist, Baer studies how people’s bodies use food and what effects those foods have on health.

Energy in, energy out

Food contains three main types of nutrients that deliver energy: fats, proteins and carbohydrates (which are often simply called carbs). A process called metabolism first cuts these molecules into small pieces: Proteins break down into amino acids, fats into fatty acids and carbs into simple sugars. Then, the body uses oxygen to break down these materials to release heat.

Most of this energy goes toward powering the heart, lungs, brain and other vital body processes. Exercise and other activities also use energy. Energy-rich nutrients that aren’t used right away will get stored — first in the liver, and then later as body fat.

In general, someone should eat the same amount of energy each day as his or her body will use. If the balance is off, they will lose or gain weight. It’s very easy to eat more calories than the body needs. Downing two 200-calorie donuts in addition to regular meals could easily put teens over their daily needs. At the same time, it’s nearly impossible to balance overeating with extra exercise. Running a mile burns just 100 calories. Knowing how many calories are in the food we eat can help keep the energy in and out balanced.

Counting calories

Almost all food companies and U.S. restaurants calculate the calorie content of their offerings using a mathematical formula. They first measure how many grams of carbohydrates, protein and fat are in a food. Then they multiply each of those amounts by a set value. There are four calories per gram of carbohydrate or protein and nine calories per gram of fat. The sum of those values will show up as the calorie count on a food label.

The numbers in this formula are called Atwater factors. Baer notes that they come from data collected more than 100 years ago by nutritionist Wilbur O. Atwater. Atwater asked volunteers to eat different foods. Then he measured how much energy their bodies got from each one by comparing the energy in the food to the energy left over in their feces and urine. He compared numbers from more than 4,000 foods. From this he figured out how many calories are in each gram of protein, fat or carbohydrate.

According to the formula, the calorie content in a gram of fat is the same whether that fat comes from a hamburger, a bag of almonds or a plate of French fries. But scientists have since found that the Atwater system isn’t perfect.

Baer’s team has shown that some foods do not match the Atwater factors. For example, many whole nuts deliver fewer calories than expected. Plants have tough cell walls. Chewing plant-based foods, such as nuts, crushes some of these walls but not all. So some of these nutrients will pass out of the body undigested.

Making foods easier to digest through cooking or other processes also can change the amount of calories available to the body from food. For example, Baer’s team has found that almond butter (made of pureed almonds) provides more calories per gram than whole almonds. The Atwater system, however, predicts each should deliver the same amount.

Another issue: Microbes living in the gut play a key role in digestion. Yet each person’s gut houses a unique mix of microbes. Some will be better at breaking down foods. This means that two teens might absorb a different number of calories from eating the same type and amount of food.

The Atwater system may have problems, but it’s simple and easy to use. Though other systems have been proposed, none have stuck. And so the number of calories listed on a food label is really just an estimate. It’s a good start for understanding how much energy a food will give. But that number is only part of the story. Researchers are still sorting out the calorie puzzle.