Deep drilling at sea

Drilling holes deep into the seafloor unveils the ocean's past and hints at Earth's future.

Beakers and chemical bottles sit on shelves, just like in a normal science lab. High-powered microscopes, incubators for growing bacteria, and other equipment line the room, just like in a normal science lab.

But, once you feel the floor start to sway or you look out the windows only to see a vast expanse of blue, you know this is no typical science lab. Instead, the seven floors of research space are a “floating university” on board a ship called the JOIDES Resolution.

|

|

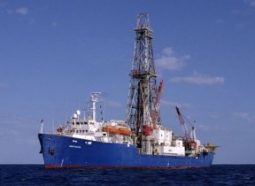

The JOIDES Resolution drillship is 469 feet long and 69 feet wide. The ship’s derrick towers 202 feet above the waterline.

|

| Integrated Ocean Drilling Program |

Last June, the 60 scientists aboard the Resolution set sail for the waters off British Columbia. They drilled holes deep into the ocean floor and conducted experiments that they hope will provide clues about what’s happening in these largely unexplored areas.

“We know more about Mars and the moon than we do about the ocean and its evolution,” says Steve Bohlen. He’s president of the Joint Oceanographic Institutes, the organization that manages the expedition.

This month, the ship is in waters off Costa Rica, drilling more holes deep into the seafloor. It will later head for the North Atlantic, looking for evidence of climate change in the distant past.

Deep knowledge

To study the layers of mud, silt, and rock that lie beneath the sea, scientists take core samples. They gather these long tubes of material by drilling a narrow, vertical hole into the crust. The researchers then analyze the material, layer by layer.

|

|

The drilling derrick looms above the research ship.

|

| Kate Ramsayer |

A tube’s different layers of rocks and sand and tiny fossils of ancient organisms provide a timeline of what happened on Earth in a given location over the last 200 million years or so.

The first ocean drilling program in 1968 gave scientists evidence that Earth’s crust was divided into huge plates. These plates slowly move around, spreading apart, slipping under, or rubbing past each other.

Since then, researchers have used cores from around the world to track changes in climate or understand why some areas are rattled by earthquakes. One core drilled near Florida contained greenish glassy particles. Geologists say the particles are evidence that a hefty meteorite slammed into the Gulf of Mexico 65 million years ago.

The new drilling program aims to delve even deeper into the mysteries of the ocean.

It’s the biggest earth science program we have, says Andrew Fisher. He likens it to the Hubble space telescope, which astronomers have used to probe outer space and make discoveries about the universe. Fisher is a professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and was one of the leaders of the Resolution‘s June expedition.

Resolution research

Research continues nonstop aboard the Resolution. The crew and scientists work in rotating, 12-hour shifts, with no days off, for all the days the ship is at sea. Expeditions can last as long as 55 days.

|

|

Researchers examine core samples obtained by drilling into the seafloor.

|

| Ocean Drilling Program |

To gather data, an experienced crew lowers drill pipe through thousands of feet of water in order to grind through 2,000 feet of mud and rock. Sometimes, they have to locate a hole bored into the seafloor years before so that researchers can obtain a fresh sample.

Getting the drill pipe into such a hole is like standing on top of the Empire State Building and trying to get a straw into a Coke bottle on the ground, says staff scientist Adam Klaus of Texas A&M University in College Station.

To provide a steady platform, the ship has special engines to keep it in place, even in choppy seas.

When technicians remove a sample from the drill pipe, the call of “core on deck” brings the scientists running. They immediately label the core sample and split it down the middle. One half is carefully wrapped up and archived so that scientists can study it later.

The other half is subjected to all kinds of tests, right on the boat.

|

|

Researcher Adam Klaus touches an instrument used to measure the density and composition of sediment cores.

|

| Kate Ramsayer |

Microbiologists quickly isolate samples in a sterile environment so that rock-dwelling bacteria won’t suffer contamination. Geologists describe the sediment layers and take measurements of their volumes, densities, and magnetic properties. Scientists box up samples to take to their home laboratories.

Earth’s plumbing system

In the holes left by the drill pipes, researchers stash sensors that detect and record temperature, pressure, and water seepage in the rock surrounding the hole. These sensors will gather data for a few years before the scientists send robot subs to collect the information.

Fisher and his colleagues plan to establish a network of sensors in the ocean floor to study water flow in Earth’s crust. Eventually, they hope to be able to pump water into one hole to see if it comes out in another hole. Such experiments will tell them more about how the “plumbing system” within Earth’s rocks works.

Other investigators are excited about the tiny microbes that can live in rocks more than 2,000 feet below the surface.

Oregon State University graduate student Mark Nielsen is interested in how the microbes store and handle energy deep within the rock. These microbes can’t use photosynthesis—there’s no sunlight—or many of the other processes used by bacteria. Neilson’s samples may tell him which chemical compounds the organisms take up.

Such studies could be useful in the search for life on other planets. Some scientists have suggested that, if life exists on Jupiter’s moon Europa or Saturn’s moon Titan, it could resemble the microbes that dwell in the equally hostile environment of Earth’s crust.

Life on a boat

Working on a research ship isn’t always easy. The scientists are away from family and friends for almost 2 months. Although they have access to e-mail, all 110 people on board the ship must share one telephone for personal calls.

Plus, with 12-hour working days and labs that don’t always have windows, a researcher’s sense of time can get out of whack.

“You can’t tell the day, and time doesn’t matter,” says Verena Heuer. She’s a microbiologist from Bremen University in Germany. “It’s just the sea and you and the ship,” she says.

|

|

Scientists and staff aboard the research ship share rooms with one or three other people.

|

| Kate Ramsayer |

Two days before the ship’s departure, Heuer and some friends took long walks. Once they were aboard, their strolling options were strictly limited.

Packing for the trip often included special personal items. Klaus brought pictures of his family. Nielsen stocked up on chocolate, Sour Patch Kids, and books. He also bought an iPod music player specifically for the trip. Heuer packed coffee and said that as long as she didn’t run out of chocolate, she’d be a happy camper.

For the scientists, the chance to be with other scientists to share ideas, ask questions, and conduct experiments makes up for the tough living conditions.

“I’m always humbled when I come to a port and see a ship waiting and know I get to go out on it,” Fisher says. “There are people from all different countries doing all different kinds of research. There’s nothing like it in the world.”

Going Deeper:

News Detective: Kate Visits a Research Ship

JOIDES Resolution Facts

From January 1985 to September 2003, the JOIDES Resolution operated for 6,591 days, traveling a total distance of 355,781 nautical miles, visiting 669 sites to drill 1,797 holes and recover 35,772 cores. Its deepest hole penetrated 6,926 feet (1.31 miles) into the ocean floor.

The ship itself is 469 feet long and 69 feet wide. Its derrick rises 202 feet above the waterline. The crew positions the ship over a drill site using 12 computer-controlled thrusters as well as the main propulsion system. The rig can suspend as much as 30,020 feet of drill pipe to an ocean depth as great as 27,018 feet.

Source: www-odp.tamu.edu/shipstats.html and www-odp.tamu.edu/shiphist.html (Ocean Drilling Program, Texas A&M University)