Racial discrimination may aggravate asthma, study finds

Kids of color suffer more from asthma, and doctors are digging deeper to find out why

This girl is using an inhaler to treat an asthma attack. Kids who suffer from racial or ethnic discrimination are more likely to develop a type of asthma that daily medicines may not control very well.

IPGGutenbergUKLtd/iStockphoto

African American children are twice as likely as whites to develop asthma, a disease that makes it hard to breathe. Black children also are more likely than white kids to die from the disease. Doctors have been puzzled by these differences. Now a study finds evidence that racial bigotry may play some role in making asthma in black children especially hard to control.

The new data find a correlation between discrimination and hard-to-control asthma. Such a link can never prove racial bias was responsible (see Explainer, just below). But it can point to a possible explanation — one that calls for more study.

In fact, the new study’s findings make some sense, says Esteban Burchard. He’s a lung doctor at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), who worked on the project. He also is Hispanic, noting that his ancestors include Native Americans, Europeans and Africans. Stress can mess with the body’s immune system. Asthma is one type of immune disease, he notes. And discrimination based on race or ethnic heritage is one type of social stress.

“Asthma clearly is due to genetics and environmental factors,” Burchard says. And knowing that social stressors are one type of environmental factor, his group decided to look at whether racial bias might play some role.

And they now report signs it can. They shared their findings June 13 in PLOS ONE. Additional information appears in a companion report in the April issue of Chest, a medical journal.

‘Not just one disease’

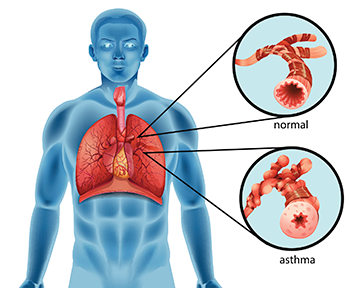

Symptoms of asthma include wheezing, coughing, shortness of breath, tightness in the chest and other problems. Some 6.2 million American children suffer from this disease, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

“We used to think all asthma was allergic,” says Neeta Thakur. That’s why doctors often prescribe allergy medicines to treat asthma. But allergies explain only four to six out of every 10 cases of asthma, points out this lung doctor on Burchard’s team at UCSF.

So “asthma is not one disease,” she says Just as someone might take different routes to school, different problems can lead to asthma. In terms of this disease, “We’re trying to figure out the other pathways.”

Burchard’s group had already collected information from many African American children and teens in the San Francisco Bay area. The new study used data from more than 1,000 of them.

The researchers asked about whether the children and teens had been exposed to tobacco smokers, had attended daycare and other matters. The researchers also had data on each person’s medical history and treatments. For instance, many kids took a daily medicine to control their disease. When an asthma attack did occur, such kids often took a so-called “rescue” medicine. One type is albuterol (Al-BU-tur-ol). It helps open up the lungs’ airways.

Tests at a clinic or office also measured each person’s response to the rescue medicine. In this instance, it was given when there wasn’t an asthma attack. A strong response now pointed to airways that were especially reactive, or twitchy. And that meant daily medicines were not doing a good job at keeping their asthma under control.

Finally, the young people were asked about any incidents of discrimination. For example, had they been prevented from doing something at school or in other situations because of their race or ethnic group? Did people hassle them because of their ethnic group, skin color or language?

Nearly half — 49 percent — reported facing such racial or ethnic bigotry.

Half of the teens and younger kids who faced this discrimination also had poorly controlled asthma. In contrast, only one-third of kids who reported no history of discrimination had poorly controlled asthma.

What the blood showed

Each person who took part in the study supplied a sample of blood. The researchers examined its plasma. That’s the liquid that holds red and white blood cells. It’s also where a protein called TNF-alpha shows up. High levels of this protein have been linked to a form of asthma that scientists think is related to environmental and social stresses, Thakur explains.

Levels of TNF-alpha varied among the kids who reported episodes of discrimination. The team homed in on the group who had the highest levels of this protein and who also faced racial bigotry. On average, their response to the rescue medicine tended to be the strongest. So their asthma was very poorly controlled.

This confirms, says Thakur, that people with that stress-related asthma will likely have more trouble controlling it if they also face discrimination. She now suggests that if patients of color have ongoing asthma problems, doctors should ask them about any social stress they may feel.

Discrimination isn’t the only type of stress that people of color may face. Thakur plans to spend several years tracking health and social experiences in a group of African Americans and Latinos. During that time, her team will also monitor urban air pollution in their neighborhoods. Her team hopes to learn more about the role of social and environmental factors in asthma.

Probing other possible factors

Lara Akinbami is a pediatrician at the National Center for Health Statistics in Hyattsville, Md. There, she works as an epidemiologist — a disease detective — who focuses on childhood asthma. She did not take part in the new study. But she too has been probing racial trends in asthma.

In one 2014 study, she and other scientists showed that in America, black children are twice as likely as whites to develop asthma. Moreover, that racial gap in asthma rates grew between 2001 and 2010. Over that time, the numbers of affected black children jumped about 40 percent, while rates in white kids remained largely unchanged.

Curious about why, Akinbami and her colleagues dug deeper. They already knew obesity could play a role in asthma. And childhood obesity has been more common in black children than in whites. Many doctors, she noted, had wondered “if the asthma patterns we see in the population — asthma going way up in black children — had anything to do with obesity rates.”

So her team studied U.S. rates of this disease (yes, obesity is a disease). And it rose in kids between 2001 to 2010. But asthma rates in black and white children did not change much over that period. So, Akinbami now concludes, “You don’t really need fancy math to see that obesity isn’t the answer.” Her group’s data on this have just been published in the July 14 Annals of Epidemiology.

“We have to keep looking for that answer” on why asthma rates are growing faster for black children, Akinbami says. Indeed, that’s why she finds the study by Burchard and Thakur’s team so interesting. It found that children who reported discrimination had more reactive airways. And that suggests they had more poorly controlled asthma. But Burchard and Thakur’s group “went a step further,” Akinbami adds. They also found a link to a specific type of asthma — one that has been linked to stress.

“We don’t know all the reasons why this racial divide exists for developing asthma or for suffering from its consequences,” she says. “But a bunch of people are working on it.”