As trees come down, some hidden homes are disappearing

A wildlife housing shortage is developing around the world among animals that depend on tree hollows

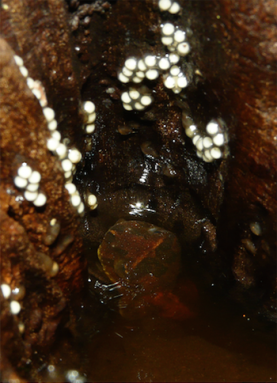

Scientists in India found these frogs living in tree cavities.

S.D. Biju/S.D Biju et al/PLOS ONE 2016 (CC-BY 4.0)

By Roberta Kwok

One evening in May 2007, two scientists in a forest in India heard a curious noise. It sounded like “tik-tik-tik,” “croink-croink,” recalls one of the researchers, Sathyabhama Das Biju.

Biju is an amphibian biologist at the University of Delhi in India. He knew that frogs were likely making the sounds. But the calls came from high in the trees, and he couldn’t climb up to investigate.

The next day, Biju returned with a boy named Tengbat from a nearby village. The teen easily scrambled about 10 meters (33 feet) up into the trees without any ropes or ladder. “He’s a magical boy,” Biju says.

Tengbat discovered that the noises came from brownish-green frogs with oval-shaped heads and long legs. The frogs were living inside hollows in the trees’ trunks. Like apartments in high-rise buildings, these holes provided the animals with homes.

Biju’s team set out to identify the frog. They eventually figured out that the species had been first observed in India about 140 years ago. No one had seen it since then. People had assumed it was now extinct. The frogs, though, had just been hiding overhead in the tree hollows. The scientists published their results last year in PLOS ONE.

This frog is just one of many creatures that take refuge in such tree cavities. From owls in Japan to pythons in Australia, wildlife around the world nestle into these nooks. Inside the holes, the animals raise their young and hide from predators. The cozy homes also protect their inhabitants from snow, rain and other harsh weather.

But the number of tree hollows is shrinking. People are clearing forests to sell the wood or to make space for farms and buildings. In cities, people often cut down big old trees because they’re afraid they might topple or that they will drop branches and hurt someone.

Scientists are investigating how the loss of tree hollows affects wildlife — and what to do about it. One team in Australia found that birds and small mammals may be fighting over scarce hollows in cities. Scientists in South America learned that it’s important to conserve trees with cavities on farms, not just in pristine forests. And some researchers are taking desperate measures to restore these wildlife dwellings.

Biju is concerned about the frogs that his team found. They discovered these frogs need the hollows to breed. Females lay jelly-covered eggs in the nooks, and those eggs stick to the sides of the cavities. When it rains, water fills the bottom of the hollow. After the eggs hatch, the tadpoles swim in the water and grow.

But hollow-bearing trees are dwindling. “I’m really, really worried,” Biju says. “The future of this amazing animal is fully dependent on the tree holes.”

Where hollows come from

There is no single way to make a tree hollow. Woodpeckers are a group of birds found on all continents but Australia and Antarctica. A woodpecker hammering the wood with its beak can gouge a hole in a tree within a few weeks or months. It will use that hollow during breeding season then usually abandon it. Other species may later move in.

Some cavities form when a tree is damaged. Lightning might strike the trunk, or strong winds might break off a branch. It’s “like getting a cut in your skin,” explains Adrian Davis. He is an ecologist at the University of Sydney in Australia. Fungi, bacteria and termites may eat away at the damaged site, creating a hollow. This process can take hundreds of years.

Once a hole forms, many animals can use it. Bats squeeze into small crevices. Birds nest in the hollows. Some cavities are even big enough for bears to enter and hibernate.

Tree hollows are particularly important in Australia. More than 300 bird, mammal, reptile and frog species need the holes to survive. “They can’t live anywhere else,” says David Lindenmayer. He is an ecologist at Australian National University in Canberra. “They use them for everything.”

But once a tree is cut down, it’s hard to replace its hollows. Australia doesn’t have any woodpeckers. All the cavities have to form the slow way. And they’re not being created fast enough to replace the homes being lost.

An urban housing shortage

Tree hollows are particularly scarce in urban areas. A lot of trees in cities and surrounding suburbs have been cut down. Davis wondered whether animals in these areas were competing for the remaining homes. If there weren’t enough tree cavities left, some species could be pushed out.

Davis decided to investigate. He installed video cameras near 61 tree hollows. Some were in forests in national parks. Other hollows were in patches of trees, called bushlands. These bushlands are the fragments of habitat left behind after people construct houses and other buildings. The bushlands Davis monitored were in the suburbs of Sydney.

Davis had to climb as high as 20 meters (66 feet) to set up the cameras. First, he used a giant slingshot to shoot a rope over a high branch. “That was the best part,” he says. Then he tied one end of the rope around the base of the trunk. He then would climb up the other end to reach the tree hollow.

Once, the branch broke while he was climbing. Luckily, he didn’t get hurt. At the time, he was only about 2 meters (some 7 feet) off the ground.

Another time, birds called cockatoos started chewing on the rope as he was climbing. Davis had to shake the rope to shoo them away. “They’re cheeky,” he says.

Davis monitored each hollow for about six months. When he watched the videos, he saw differences between trees in the suburbs and those in forests. Suburban animals visited the hollows about three times more frequently than did those in national parks.

Suburban dwellers also fought with each other more. Birds called rainbow lorikeets defended their hollows against other birds, such as sulphur-crested cockatoos and laughing kookaburras. In one video, the cockatoos attacked a common brushtail possum that had entered their hollow. “There were feathers and fur actually flying,” Davis says.

The animals might visit suburban hollows and fight more often over them because they are scarcer. If there are not enough cavities for everyone, some animals might try to steal other animals’ hollows. All that fighting could stress out the animals, Davis suggests.

Story continues below video.

Last year, Davis started a citizen science project in Australia called Hollows as Homes. Ordinary people, including kids, can monitor a tree cavity and report which animals are using it.

The information could help managers decide whether it’s okay to cut down certain trees. For example, if someone sees an endangered owl using a hollow, the city wouldn’t be allowed to cut down that tree.

“We can’t just keep clearing habitat,” Davis says.

Living on the farm

In another part of the world, Kristina Cockle has investigated how best to preserve hollow-bearing trees. Cockle is an ecologist at the National Scientific and Technical Research Council in Salta, Argentina.

Cockle knew it was important to protect hollow-bearing trees in pristine forests. But what about on farms or in partly logged forests, where some trees already had been cut down? Maybe baby birds raised at those sites wouldn’t have a good chance of survival anyway. For instance, less food might be available. Or animals here might now be more vulnerable to predators. So if hollows in farmland or logged forest didn’t provide useful habitat, they might not be worth investing a lot of effort into keeping their trees. Money and conservation projects might provide bigger benefits elsewhere.

To find out, Cockle’s team studied nests in 98 tree cavities in northeastern Argentina. Some were on farms. Others were in partly logged forest. Still others were in pristine forest.

The researchers spied on the hollows in a couple of ways. Sometimes they climbed a ladder or rope to get to the cavity. Then they put a tiny camera in the hole. Other times, the team used a long pole to hoist a camera to the hollow.

Cockle and her colleagues checked the same hollows over and over. They recorded how many eggs or baby birds remained from one visit to the next. Sometimes the parent birds attacked the researchers while they tried to peek at the nest. For instance, Cockle recalls a “clowny-looking bird” called a surucua trogon once flew straight at her.

The scientists discovered that tree hollows on farms and in logged forests were being used. Not only that, baby birds raised in those cavities fared pretty well. They were just as likely to survive as were the ones raised in pristine forests.

What appeared to matter more was where a tree hollow was located. For example, some birds were more likely to survive if they were raised in hollows high above the ground that had small openings. Predators would find it harder to enter such a nook. Cockle’s team published its findings two years ago in Biological Conservation.

This research suggests that tree hollows, no matter where a tree is, are valuable. “All cavities matter,” Cockle concludes. “We should work to conserve cavity trees even if they are in an isolated tree in a pasture full of cows.”

Resurrecting trees

People have tried to replace tree hollows with artificial homes called nest boxes. Typically made of plywood, these can be attached to a pole or the side of a tree. Animals can enter the box through a hole and live inside.

Sometimes, nest boxes work well. For example, bluebirds lost a lot of tree-hollow habitat in North America. In addition, some new bird species that arrived from other countries stole existing bluebird homes. Installing nest boxes helped some bluebird communities recover.

But nest boxes are not tree hollows. They may not always work as well as the real thing. They may not protect animals from heat and cold as effectively. Making and installing a lot of these boxes can be expensive. They won’t last as long as a tree’s hollow. And pests, such as common bees, can hog the boxes, displacing other animals.

Plus, old trees have other important features besides hollows. Their big canopies provide shelter. They have peeling bark, where insects such as beetles and ants can live. And they produce lots of nectar and seeds that birds can eat. “We’ve got to keep them around,” says Darren Le Roux. He is an environmental project officer at the Australian Capital Territory Parks and Conservation Service in Canberra.

So Le Roux is trying a radical approach. In 2016, his team selected large trees in the Canberra suburbs that were being cut down because they were considered unsafe. Tree experts, called arborists, used a crane truck to move the trees onto a giant semi-trailer.

Then Le Roux and his colleagues hauled the trees to a site near the Molonglo River. A forest here had been cut down. The researchers now wanted to restore woodland habitat at the site for wildlife. Using the crane, the team propped up each tree within a steel cylinder anchored by a concrete base. The cylinder extended about 1.5 to 2 meters (5 to 7 feet) into the ground. The dead tree could thus stand upright — branches, hollows and all.

The researchers are monitoring the resurrected trees to see if animals use the hollows. The team also has planted new trees, but those young trees will not form hollows for about two centuries. In the meantime, the propped-up old trees could offer dwellings to some homeless animals.

“We’re trying to bypass the incredible time period it takes for a little tree to turn into a big tree,” Le Roux says. Even dead trees can support wildlife for decades.

Le Roux’s strategy might seem dramatic. But he is worried that without help, hollow-dwelling animals may go extinct. “They’re losing their habitat left, right and center,” he says. “We need to do something here on an epic scale.”