Cassini spacecraft takes its final bow

The NASA spacecraft has revealed a lot about Saturn during its 13 years in orbit

Saturn’s north pole was dark when Cassini arrived in 2004. But as the seasons changed, light illuminated a bizarre six-sided swirl of gases at the pole (shown here in false color). The hexagon has been known since the 1980s. It is about 30,000 kilometers (18,600 miles) wide with a massive hurricane centered on the north pole.

JPL-CALTECH/NASA, SPACE SCIENCE INSTITUTE

The Cassini spacecraft’s 20 years in space has been a marathon performance. It’s orbited Saturn more than 200 times. Along the way, it’s taken hundreds of thousands of images of the giant planet, its splashy rings and its many moons. On September 15, though, Cassini will use its last burst of fuel to plunge into the sixth planet from the sun. With awe and nostalgia, scientists and space enthusiasts the world over will watch it disappear.

“It’s hard not to anthropomorphize the spacecraft,” says Matthew Tiscareno. He works at the SETI Institute in Mountain View, Calif. And this astronomer has been working on Cassini since it entered Saturn’s orbit in 2004. “We’ve been riding on its back for these 13 years. And it’s done everything we’ve asked,” he says. “I think it’s the most spectacularly successful mission that NASA has ever run.” (NASA is short for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.)

Cassini was designed to train its 12 scientific instruments on the Saturn system for just four years. NASA, however, extended the mission twice. Even with the extra time, Cassini’s 13-year run is less than half of one year on Saturn. There, a year lasts 29 Earth years.

After all this time, we’ve witnessed only the transitions to Saturnian spring and summer. That’s the equivalent of January to June on Earth’s Northern Hemisphere. And yet we’ve seen so much.

Cassini has revealed massive churning storms that rage for decades. It’s allowed the study of rings that may be the best laboratory for learning how planets form. And it’s unveiled details of some of Saturn’s more than 60 moons. Two of those natural satellites — Titan (TY-tun) and Enceladus (En-SEL-uh-dus) — surprised Cassini scientists by having many of the right ingredients for life. The craft has revamped our picture of Saturn and its celestial family.

Saturn’s potentially habitable moons are the reason Cassini must meet a dramatic end. The mission team at NASA decided it was safer to crash the craft into Saturn itself than to risk the craft wandering off and brushing up against Enceladus or Titan. If it crashed there, it might spread earthly germs to any nascent ecosystems on those moons.

But the craft will be busy until the very end. Since April, Cassini has been making weekly dives into the possibly rubble-strewn region between Saturn and its rings. This is a zone the team hadn’t dared explore before. Plus, the craft will collect data during its last hurtle into the gas giant’s atmosphere. Those final measurements should help solve some of the most basic mysteries about the planet, including when it got its iconic rings.

“Cassini data,” says team member Ralph Lorenz, are “going to keep us busy for decades.” He is a planetary scientist at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab in Laurel, Md.

Surviving storm

In the eye of Saturn’s hexagon swirl, cloud speeds can reach 150 meters per second (340 miles per hour). The storm is shown here in false color from 2012. It has probably been there for decades, if not centuries. Saturn has no mountains or oceans to interrupt the storm.

In the eye of Saturn’s hexagon swirl, cloud speeds can reach 150 meters per second (340 miles per hour). The storm is shown here in false color from 2012. It has probably been there for decades, if not centuries. Saturn has no mountains or oceans to interrupt the storm.

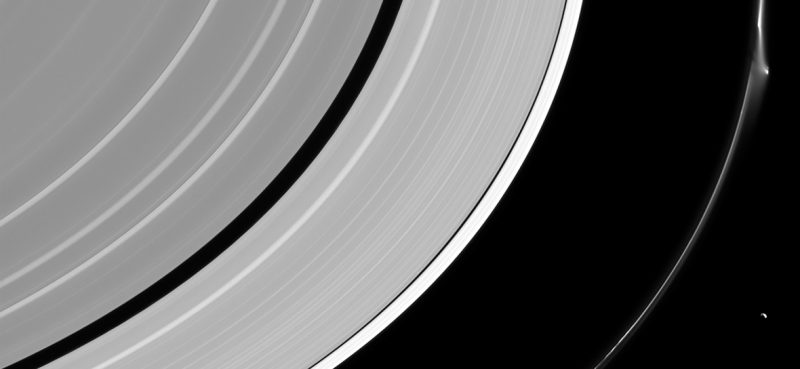

Raised ripples

Saturn’s tiny moon Daphnis orbits within the Keeler Gap in Saturn’s outer A ring. That gap is 42 kilometers (26 miles) wide. These 10 images were each taken about 90 seconds apart. The sequence shows Daphnis’ gravitational pull perturbing the particles at the gap’s edge. The moon is only 8 kilometers (5 miles) across. Still, its gravitational pull is enough to raise ripples in the rings around it. These waves were first noticed in 2009. That’s around the time of Saturn’s spring equinox. It’s when the planet’s spring begins, so the angle of sunlight made the waves stand out more. Daphnis has a ridge around its equator. It’s probably made of fine particles the moon has gathered from the rings.

Ring spikes

Saturn’s rings are “arguably the flattest structure known to man,” says Tiscareno. Over a span of hundreds of thousands of kilometers, their vertical thickness typically varies by only about 10 meters (33 feet). But Cassini snapped these structures, as tall as 2.5 kilometers (1.6 miles), in 2009, when sunlight struck the rings at a perfect angle to cast long shadows.

Lineup

Cassini caught a family portrait of five of Saturn’s moons in this image from July 2011. At far left is Janus, which is 179 km (111 mi) across. Then, to its right, comes Pandora, which is 81 km (50 mi) across and nestled in the rings. Enceladus (504 km, or 313 mi, across) appears next over. It’s half lit above the rings in the center of the image. Finally, on the far right are Mimas (396 km, or 246 mi, across), and Rhea (1,528 km, or 949 mi, across).

Titan terrain

Cassini mission scientist Ralph Lorenz has this false color image of Ligeia Mare (LIE-jhee-uh MARR-ay) hanging in his office. It’s a large sea on Saturn’s moon Titan. Cassini’s radar peered through the moon’s thick orange haze to reveal an Earthlike surface with seas, rivers and clouds filled with the liquid hydrocarbons ethane and methane. This moon could possess the ingredients for life.

“Titan has been doing prebiotic chemistry experiments for us for a huge amount of time,” says team member Elizabeth Turtle. By that she means its chemical reactions could createthe ingredients needed for life to exist. She also is a planetary scientist at the Applied Physics Lab. She, Lorenz and others are working on a proposed mission called Dragonfly. It would land drones on the moon to sample its surface.

Titan is the only place in the solar system — other than Earth — known to host long-lived liquid lakes and streams. But on Titan, the liquid is mostly methane and ethane. The video below combines radar images of Titan from 2004 to 2013 as Cassini flies over its two largest seas, Kraken Mare and Legia Mare. Where the lakes look dark, the liquid is exceptionally still and flat as a mirror.

Inner orbits

By guiding tiny particles around themselves, small moons embedded in Saturn’s rings create the propeller-like features seen here. Scientists have followed these objects for more than a decade. They’ve even named the larger ones after pioneers of aviation. These images, taken February 21, 2017, show two views of Santos-Dumont, named for a Brazilian-French aviator. “This is the only time in the history of astronomy that we’ve tracked the orbit of an object that is orbiting in a disk,” says Tiscareno of the SETI Institute. Studying the propellers can help reveal how planets that form in the disk of gas and dust around a young star grow.

Icy jets

One of the biggest surprises of the Cassini mission was that the icy moon Enceladus is spewing its guts into Saturn’s rings. These jets from the moon’s south pole come from a subsurface ocean. That ocean may have the right chemistry for life. The jets also supply icy material to one of Saturn’s rings.

Plume power

This false color image from 2005 shows the reach of the spectacular plumes on the moon Enceladus. Later sampling by Cassini revealed that the plumes contain molecular hydrogen, ammonia and a variety of organic compounds. All are signs that this moon might be habitable. NASA is considering a mission to go back and sample the plumes.

This false color image from 2005 shows the reach of the spectacular plumes on the moon Enceladus. Later sampling by Cassini revealed that the plumes contain molecular hydrogen, ammonia and a variety of organic compounds. All are signs that this moon might be habitable. NASA is considering a mission to go back and sample the plumes.

Southern lights

Southern lights

Cassini spotted Saturn’s shimmering aurora dancing near its south pole in July 2017. The bright spots shooting across this video from the bottom left are due to charged particles hitting the detector. Behind the spots, you can see the aurora’s ghostly glow. These light shows are created when charged particles from the sun strike the planet’s atmosphere and make its gas glow.

Moon sculptor

Saturn’s outer ring is called the F ring. It’s sculpted by tiny moons that pass by. The ring’s dust and ice particles are tugged by the moons’ gravity. These images from Cassini, taken between 2006 and 2008, show various disturbances in the F ring.

Saturn’s outer ring is called the F ring. It’s sculpted by tiny moons that pass by. The ring’s dust and ice particles are tugged by the moons’ gravity. These images from Cassini, taken between 2006 and 2008, show various disturbances in the F ring.

Mother Earth

This iconic Cassini image is known as “The Day the Earth Smiled.” On July 19, 2013, Cassini turned back toward its planet of origin and shot a picture with Saturn’s rings and Earth and its moon all in the same frame. It was the third time Earth was imaged from the outer solar system. But this was the first time humankind got a heads-up, so people could look up and smile or wave for the camera.