Picturing how many Great Salt Lakes Harvey dropped onto Texas

Here are some ways to visualize Tropical Storm Harvey’s mega deluge

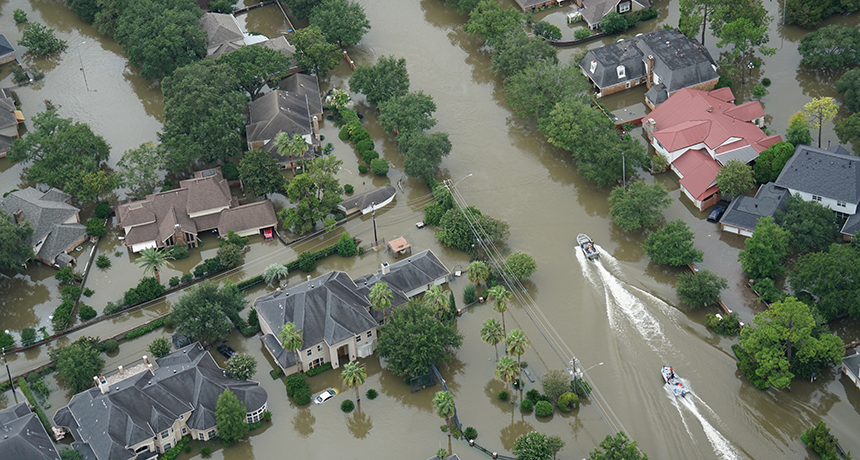

Some people needed boats to deal with catastrophic flooding, seen here, due to Tropical Storm Harvey’s astounding downpours in Texas last week. Such mega-storms could become more common, scientists worry.

Karl Spencer/iStockPhoto

Hurricane Harvey will always be known as the deadly storm that dumped a dramatic amount of water across Texas in 2017. Rain totals varied greatly from one area to the next. But an average of 76 centimeters (30 inches) fell across a region home to some six million people, the National Weather Service reported.

At least one Houston neighborhood recorded 131.78 centimeters (51.88 inches) between Friday, August 24, and Tuesday, August 29. That toppled the previous rainfall record for the continental United States.

And that, of course, wasn’t the end of it. After stalling over Texas for days, the storm went back out to sea only to make landfall again. It now could dump even more water on Texas and Louisiana. The storm then weakened into a tropical depression over the Tennessee Valley. There, it sparked more urban flooding, and unleashed a barrage of tornadoes over Alabama and Mississippi.

But the Texas downpours were what proved truly astounding. Even more mindboggling is the total quantity of water that rained down — in liters or gallons — across the Southeast Gulf Coast of Texas and Louisiana over six long days. Picturing that total is challenging, but we’ve taken a stab at crunching the numbers.

To do so, we utilized the National Weather Service’s final rainfall map. Then, by contouring different amounts of rainfall, we took the area enclosed and tallied how many liters (which we also converted to gallons) would be needed to drop that many inches of rain.

By our calculations, that cumulative rainfall would fill 13.5 trillion 4-liter buckets (or 14.3 trillion gallon buckets)! Maybe you want to think in terms of bathtubs. Harvey’s downpours would fill 178 billion bathtubs. That’s enough to give every person in the world two dozen baths — and still have leftovers.

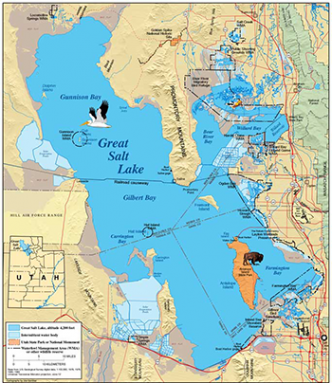

Pooled in one place, Harvey’s rains would be enough water to occupy the entire volume of Utah’s Great Salt Lake — 2.85 times. If the mouth of the Mississippi River were draining into Texas (although it doesn’t), it would take more than two weeks of its total flow to deliver all of Harvey’s water.

The Great Pyramid of Giza is huge. But Harvey’s downpours would fill this structure roughly 21,000 times. Or imagine this precipitation measured in giant “blocks” of water a kilometer (or mile) on each side. Harvey’s Gulf Coast downpour would equal 54 cubic kilometers (or 13 cubic miles). Now pour the water out of these blocks onto the streets of New York City and it would flood the city to a height of 68 meters (224 feet). That’s as high as a 20-floor high-rise office building, yet averaged across the entire length and breadth of the city.

Tipping the scales

How much does all of this water weigh? Plenty. Try an estimated 53.8 trillion kilograms (118.6 trillion pounds). That’s 184 times the weight of all of the food that is purchased in the United States each year. It’s also 8.1 million times the weight of the Eiffel Tower.

The average African elephant tips the scales at roughly 5,900 kilograms (13,000 pounds). So put Harvey’s rains on one side of a scale and you’d need more than 9.1 million elephants to sit on the other side to balance out the weight of this massive storm’s rainfall.

Even by hurricane standards, this was no average storm. Indeed, a storm that can drop this much rain is approaching a “once-in-a-million-year event.” That assessment comes from a 1978 report by the U.S. Army and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Meteorologists and climatologists alike note that it’s impossible to say any one storm is caused by climate change. However, they have already been suggesting that Harvey shows the “fingerprint” of climate change. By that they mean that it is likely that Harvey was made worse due to environmental changes made by human activities.

A role for Arctic warming?

Charles Greene directs the Ocean Resources and Ecosystems Program at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y. “Houston would have suffered much less damage,” he says, if Harvey behaved like an ordinary hurricane. “But instead, the storm stalled in place and just continued to dump record amounts of rainfall from the Gulf on the city.” Harvey’s unusual four-day stall meant that it could unleash unprecedented amounts of rain.

So what role could climate change have?

A swift river of west-to-east winds, known as the jet stream, flows in the upper atmosphere. It divides cold Arctic air in the north from warmer, subtropical air in the south. As the Arctic warms, these winds in the upper atmosphere weaken. Normally, the jet stream gently undulates up and down. But with Arctic warming, it becomes wavier. Climate scientists believe that North American storms will have a greater chance of stalling as this occurs. And that ups the threat of very heavy rain events where clouds are able to dump more of their precipitation in one place.

What’s more, as Earth has been warming, the ability of the air to hold moisture also has climbed. So far, there has been a worldwide average temperature increase of between 1 degree and 2 degrees Celsius (1.8 degrees and 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) since the start of the Industrial Revolution.

Why the broad range? The total depends on how researchers have measured it. Some estimates take into account ocean temperatures. Others only average the observed rise in the atmosphere. The atmosphere’s growing fever has boosted the amount of water vapor available for a storm to store — and eventually release. Harvey tapped into this extra humidity. And then released it as super-heavy rains.

NOAA already has noticed a sharp uptick in the number of “extreme” precipitation events over the northeastern United States. In a report it issued four years ago, the agency described a ”recent elevated level in extreme precipitation.” Extreme events are not just becoming worse — they’re becoming more common, too, the report concluded.

Another symptom of global warming is a planet-wide rise in sea levels. And that has increased the risk of damaging storm surges — storm-related tidal rises that send an influx of seawater into coastal communities. A century-long plot of the sea level at Galveston Island, Texas, for instance, shows that the ocean has risen nearly a half-meter (19.7 inches) in the past 150 years or so. (These data come from a study conducted by Texas A&M University at Corpus Christi.)

With higher sea levels, there is an increased risk of water being swept inland and causing destruction. This is especially true for hurricanes that come ashore. This is known as storm surge flooding.

The future of weather is directly related to Earth’s climate. As that climate changes, so will the weather. Signs now point to weather everywhere becoming more extreme. As Texas continues to pick up the pieces from catastrophic flooding, we have to ask ourselves: Could events such as Harvey become the new normal?