Expedition finds South Pacific plastic patch bigger than India

Most of the oceanic garbage is tiny, confetti-sized bits

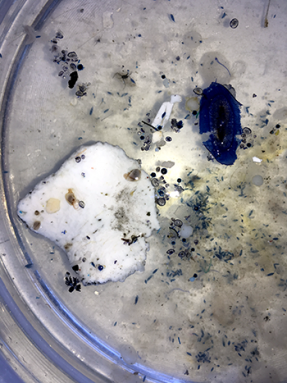

Charles Moore looks at the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Chile in March. His team found that an enormous floating garbage patch there held a mix of fishing gear and tiny plastic bits.

courtesy of Algalita

By Ilima Loomis

Imagine gazing out on the beautiful, calm open ocean — then looking down and seeing water that looks dusty because it’s clouded with tiny particles. That’s what Charles Moore saw while sailing earlier this year. Moore and his team were on an expedition to learn about pollution in the South Pacific Gyre. This is an area in the Pacific Ocean, west of South America. When they got there, they found that it was full of trash — especially tiny bits of plastic.

A gyre is a huge area of ocean, thousands of kilometers (miles) across, where ocean currents move in a large circle. Scientists have known for years that trash gathers in these swirling currents. The most famous of these floating dumps is the “great Pacific garbage patch.” It’s in the North Pacific Gyre, between California and Hawaii.

Researchers discovered the garbage patch in the South Pacific Gyre in 2011. But Moore wanted to study its size and shape. He also wanted to know what kind of trash it contained. Moore is the founder of Algalita, a nonprofit organization for studying plastic pollution in the ocean.

In November 2016, Moore and his team set sail from California aboard the research ship Alguita. They cruised south to explore the polluted water. As they sailed through the gyre, they dragged a fine net behind the ship to catch any trash. They would measure and study what they’d caught when they returned to their laboratory in May.

“We spent time there taking lots of samples, changing course and trying to see the limits of where it thinned out and became less prevalent,” Moore says.

Moore’s team found the edge of the south Pacific garbage patch around 1,100 kilometers (700 miles) off the coast of Chile. It stretched about 2,600 kilometers (1,600 miles) west to Easter Island. Altogether, it covers an estimated 3 million square kilometers (1.9 million square miles) of the ocean. That’s bigger than the country of India. The size and oval shape matched what scientists had predicted in models. “The scale is tremendous,” Moore says.

There was more trash at the center of the gyre than around the edges. And the types of plastic in the South Pacific Gyre were a little different than those in the North Pacific Gyre, Moore says. For one thing, there were more pieces of tangled fishing line and other fishing gear in the south. That’s probably because there is a lot of fishing activity in the area.

But most of the trash they found was tiny bits of plastic. This is also called microplastic.

“We’d stand on the bow and see hundreds of pieces in a few minutes. But they’re small,” Moore says. “It looks like plastic dust on the ocean.” The great Pacific garbage patch in the north is also mostly microplastic, but Moore describes the southern garbage patch as “not as chunky.” When his team got back to the lab, they found that most of the plastic bits they’d collected were 1 to 3 millimeters (0.4 to 0.12 inch) across. Moore plans to publish a research paper about his findings.

Plastic smog

It’s important to realize that most of the garbage in the gyres are not big pieces. Instead, they make up a cloud of tiny plastic particles, says environmental scientist Marcus Eriksen. “We should not be calling these things garbage patches but rather a ‘plastic smog,’” he says. Smog is a type of pollution that clouds the air with tiny particles.

Eriksen studies plastic pollution in oceans and lakes through his nonprofit organization, the 5 Gyres Institute. He discovered the South Pacific garbage patch in 2011. He says Moore’s recent trip turned up more trash than he found when he first sailed through. That could mean the amount of plastic in the water is increasing. Or it could show that pollution levels go up and down over time.

“The ocean is highly variable,” Eriksen says. But in general, he says, ocean garbage seems to be increasing.

Plastic may swirl around in a gyre for a while, but it won’t stay there forever. Eventually it will sink into deeper ocean currents that carry it around the world. That’s why ocean plastic is everybody’s problem, Eriksen says. “This ‘smog’ is diffusing around the globe. Wherever there’s seawater today, there’s microplastic.”