Capturing the Stuff of Space

A spacecraft brings comet grains and stardust back to Earth.

Comet dust and the remains of exploded stars hurtled into Earth’s atmosphere and landed safely in the Utah desert last month. The material arrived inside a capsule ejected by the Stardust spacecraft.

|

|

Carrying a cargo of comet grains and stardust, the Stardust capsule landed in the Utah desert on Jan. 15, 2006. |

| NASA/JPL |

Scientists are now teasing out tiny comet fragments from a protective gel inside the Stardust capsule. In addition, they’re asking for your help to spot the grains of stardust that the capsule also captured and brought back to Earth.

By studying these bits of space material, the investigators hope to learn more about comets, stars, and the origin of the solar system.

Long voyage

The Stardust spacecraft was launched from Earth in February 1999. Since then, it’s traveled 2.88 billion miles. In January 2004, on its second loop around the sun, Stardust brushed past the comet Wild 2.

|

|

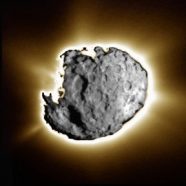

This image of Wild 2 shows the comet’s rough surface and gas streaming into space, leaving long trails. |

| NASA/JPL |

The spacecraft came within 149 miles of the comet, snapped its picture, and captured bits of comet dust in a special sample-collection tray.

Catching comet dust isn’t an easy task. Even though they’re small, the particles fly toward a spacecraft at a rate up to seven times as fast as that of a speeding bullet.

To slow down, trap, and cushion the dust, scientists filled the grids in the sample tray with a material known as aerogel, sometimes called “blue smoke.” Aerogel is a strong but extremely light substance that is 99.8 percent air.

|

|

Although aerogel has a ghostly appearance, it feels as solid and hard as a piece of Styrofoam. |

| NASA/JPL |

Scientists didn’t know what to expect when they opened the Stardust capsule on Jan. 17. They were excited to see thousands of tracks left by fragments of Wild 2.

“We were relieved that anything survived at all,” says Don Brownlee. He’s the lead scientist with the Stardust project and a professor at the University of Washington in Seattle. “We didn’t know how the particles would survive during capture.”

Carrot and hedgehog tracks

When Brownlee and his colleagues looked at the gel, they saw that the particles had left a variety of tracks when they careened into the sample tray.

Some particles went straight into the gel, leaving a carrot-shaped track as they slowed and eventually came to rest, Brownlee says. Other comet grains came apart when they hit the gel, creating a bulbous hole at the surface before narrowing to a turnip shape.

|

|

In an experiment on Earth, researchers used a special gun to fire particles into an aerogel. As the particles slowed to a stop, they left carrot-shaped tracks. |

| NASA/JPL |

Sometimes, little pieces broke off from the main comet grain, changing a turnip-shaped track into one that resembled a hairy, heavily branched root.

But when some big particles slammed into the gel, the tracks looked less like a vegetable and more like a prickly animal.

“The biggest ones made . . . cavities that people describe as hedgehogs,” Brownlee says. These particles, barely visible to the naked eye, left tracks half-a-centimeter wide. Smaller pieces broke off to form the hedgehog’s spikes.

Dust removal

The researchers have a variety of special tools to get the comet dust out of the gel. Working in a superclean room, they use tiny, computer-controlled needles that jab the material over and over again, eventually cutting out a wedge containing a dust particle. They use knives made of steel or diamond to slice along a dust track. In addition, the scientists can use microtweezers and miniature forks to snag comet grains.

|

|

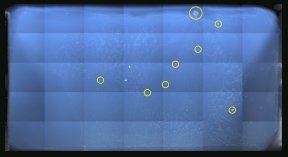

The yellow circles mark spots where large particles entered this aerogel tile, which is 4 centimeters long and 2 centimeters wide. |

| NASA/JPL |

The scientists now plan to analyze the dust to see what chemical compounds it contains.

The particles that Stardust collected date to the time when Wild 2 was created—4.5 to 4.6 billion years ago. “We believe that [these particles are] the original building blocks of the solar system,” Brownlee says.

The particles could provide answers to questions not only about comets but also about the origins of our sun, Earth, and the other planets.

A search for stardust

Scientists with the Stardust mission will also investigate interstellar dust—stardust, for short. These particles are created when a star is dying or explodes. The Stardust capsule collected samples of interstellar dust using the back of the comet-dust collector.

We can get a sense of what stardust is like from faraway observations, says Bryan Mendez, an astronomer at the University of California, Berkeley. But now, researchers will for the first time have actual samples of stardust to analyze and study.

|

|

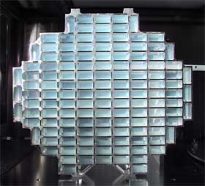

This set of aerogel tiles collected comet grains and interstellar dust. |

| NASA/JPL |

First, however, the researchers have to find the stardust. There will probably be only 45 or so particles in the aerogel. The width of each particle is less than that of a human hair, Mendez says. Looking for these particles in the sample tray is like looking for 45 ants on a football field.

So, Mendez and other scientists are seeking the public’s help.

The researchers will produce about 1.5 million “movies,” each one a set of images of a microscopic aerogel section no bigger than a grain of salt. Volunteer dust finders, who will be trained to spot stardust tracks, can then download and watch the micromovies on their Internet browsers.

Volunteers will be using their computers to do real science, Mendez says. “We need to find these particles in order to study them. With an army of volunteer scientists, we can do it pretty quickly.”

The micromovies won’t be ready until late March. But you can register to be a volunteer right now. Just go to stardustathome.ssl.berkeley.edu/. Astronomy buffs of any age can participate, Mendez says. All they need is a little bit of patience.

As a bonus, Mendez adds, anyone who finds a star speck will get to name it!

Going Deeper: