Echoes of hunting

Bats use high-pitched sounds to zero in on prey, converting what they hear into how they fly.

By Sarah Webb

If you go by what you see in cartoons or vampire movies, you might think that bats are big, scary, blood-sucking creatures that come out only at night.

Certainly, many bats are active at night and asleep during the day. They have sharp teeth. A few species do feed on blood. These vampire bats, which are actually quite small and rare, typically target birds, cattle, pigs, and other animals. When most bats are hungry, however, they stick to insects or fruit.

|

|

A big brown bat shows its sharp teeth.

|

| Public Health Image Library |

Because they usually hunt at night, bug-eating bats have developed a special system for finding insects in the dark. In much the same way as dolphins use sound to locate objects underwater, bats use information from sounds to “see” their prey in the dark. This process is called echolocation.

Scientists are studying bats and their use of echolocation to learn more about how bats process information to understand and adapt to the world around them.

High-pitched squeals

When bats use echolocation to hunt, they make high-pitched squeals that people can’t hear but that other bats can detect. If there’s a bug or another object nearby, the sound bounces off the object and comes back to the bat.

|

|

A gray bat in flight.

|

| U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service |

“They can tell where the bug is by listening to the difference in the sound at the left and right ears,” says Cindy Moss, a psychologist at the University of Maryland in College Park.

And a bat can tell how far away an object is by keeping track of the time between when it makes the sound and when the echo returns, she says. If an object is nearby, the sound comes back quickly. If the object is farther away, the reflected sound takes longer to travel back to the bat’s ear.

“They’re performing calculations in their minds all the time in much the same way that we perform calculations about what it is that we see,” says Ellen Covey. She studies bats at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Big brown bats

Moss is interested in big brown bats, which live in dark places such as attics and barns and under the eaves of buildings throughout most of the United States and Canada.

|

|

Big brown bats live throughout most of the United States and Canada.

|

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

Using echolocation, a big brown bat can swoop down, capture a bug, and eat it—all in about 2 seconds.

Scientists studying big brown bats in the wild have observed that they change both the pitch and the timing of their calls depending on whether they’re looking for food or whether they’ve already found a bug that looks like a tasty dinner.

When they’re searching for food, bats tend to use longer sound pulses to locate bugs flying in the open. When they notice a bug, they begin to make fast, high-pitched noises that, in general, get faster and higher as they close in for the kill.

Using sound like a flashlight

Clearly, bats know how to zero in on their food. They not only make appropriate sounds but also appear to have no trouble analyzing the echoes that come back to their ears.

|

|

A big brown bat captures a mealworm dangling on a thread in this lab experiment.

|

| Brown University photo by Steven P. Dear |

To learn more about how bats process the information that they gather, Moss and her coworkers set up lab experiments to see how bats use echolocation while doing simple tasks.

The researchers tied a bug to a string and hung it from the ceiling of a dark room. Then, they used high-speed infrared cameras and special audio equipment to record a bat’s calls as it hunted for the bug.

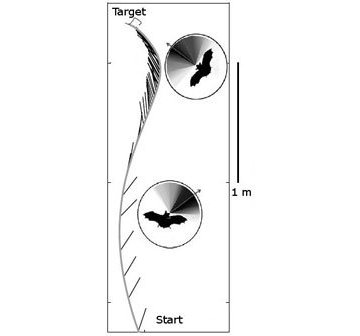

Moss and her students found a close connection between where a bat “looks” and how it flies. A bat directs its sound beam, like a flashlight, ahead of its flight. As the bat moves its head in the direction in which it calls, its body turns in the same direction

|

|

This illustration shows the direction in which a bat’s sound beam points at different times, as seen from overhead, as it searches for (widely spaced signals), identifies (closely spaced signals), and captures a tethered insect (top).

|

| Courtesy of Cindy Moss, University of Maryland |

Bats convert what they see into what they do in much the same way that people convert what they see into action. For example, if you’re hungry and see an ice cream truck to your left, your head turns to the left. Your body then turns to the left as you begin walking to the truck.

The researchers also discovered that when a bat makes calls at a fast rate as it turns, it turns more quickly than it does when calling at a slower rate.

Obstacle course

Finding a bug that’s hanging from a string in the middle of an empty room is easy for a bat. That’s because bats normally hunt in environments in which insects flit among other objects, such as trees, buildings, or animals.

To make things harder for the bats in the lab, Moss and her coworkers tied bugs to a string and hung them in front of a plant. Now, the bats would have to sort out echoes that came not only from the bug but also from the plant.

|

|

A bat tries to locate an insect tethered beside a plant.

|

| Courtesy of Cindy Moss, University of Maryland |

A plant’s echoes can serve as camouflage for a bat’s prey. In that case, a bat has a more difficult task and has to use different strategies to find the prey, Moss says.

The researchers found that, when the hanging bug was 20 centimeters from a plant, a bat located the bug about 80 percent of the time. When the bug was 10 centimeters from the plant, the bat needed more time and caught a meal about half as often.

When the bug was hanging 40 centimeters away, the bat hunted almost as efficiently as if the plant weren’t in the room.

So, even with extra, misleading echoes, bats can find food. But, it turns out, they adjust the timing of their signals to help make up for the clutter.

Decoding sounds

Many bat researchers have studied both the length and pitch of individual sounds that bats make as they hunt. In their studies, Moss and her coworkers observed something new. Bats can adjust their sound output to respond to information they receive by echolocation. What’s more, they produce pulses in distinctive patterns.

When bats hunt for a bug against a background object, they repeat particular patterns of sound, Moss says. She calls these patterns strobe groups. They resemble the repeated flashes of a strobe light.

“We started seeing sound groups again and again and again,” Moss says. “And we did some recording in the field, and there they were.”

Such groups of sounds may allow a bat to sharpen its view of a space and help it recognize the difference between an insect and shrubs or grass in the background.

The work that Moss and her students have done in identifying these patterns is a useful step in understanding how a bat processes information, Covey says.

“It’s important to look at the context of the sounds and not just the individual sounds,” she adds. Sounds mean different things depending on what went before and what comes after.

So, in the seconds that it takes a bat to swoop down and capture a meal, it’s using a complicated sonar system that scientists are only beginning to understand. There might even be similarities between the way that bats process their echolocation patterns and the way that people process sound patterns to understand speech.

That’s something to ponder the next time you’re out at night during the spring or summer and happen to glimpse a bat on the hunt.

Going Deeper: