Dirty air can harm your brain and stress the body

Studies show pollution can alter brain function in students and disrupt hormones

The year was 1952. The setting: London, England. “On December 8, cool air from across the English Channel settled over the Thames River valley and did not move. London’s 8 million residents did what they had been doing for centuries: They huddled indoors and warmed themselves by their coal stoves. Smoke ran like tap water from a million chimneys. In the motionless air, the hot vapors chilled and, instead of rising, settled back to the ground. The smoke became so thick that visibility dropped to near zero.”

— Devra Davis, When Smoke Ran Like Water, Basic Books 2002

That super-thick fog of pollution, 65 years ago, turned the air into a toxic soup that lasted five long days. Local reporters would call it the Great Smog. Inhaling the blackened air sent 150,000 people to the hospital with breathing problems. In all, some 4,000 would die. This disaster provided some of the strongest, early evidence that urban air could prove deadly.

It evolved owing to an unfortunate combination of bad weather and especially heavy pollution. Yet even today, air pollution sickens and kills people. Lots of people. A 2016 study reported that breathing dirty air is now the fourth-leading cause of deaths worldwide.

Air pollution tends to pose the biggest risk to the very old, to the very young and to people already suffering from some chronic ailments. What types? Asthma (a breathing disorder) and heart disease are two major conditions that put people at risk.

But scientists are learning that air pollution can pose serious risks to anyone. You don’t have to be old or sick. You don’t have to suck in horrible fumes or air so full of pollutants that you can see and taste them.

Indeed, emerging data show that even pollutants too small to see with the naked eye can harm healthy children and teens. That pollution can alter how their brains function. It can make it hard for kids to concentrate. It also can throw out of whack hormones — chemical messengers that direct the body’s activities. In short, it can seriously damage young minds and bodies.

Polluting the brain

Lilian Calderón-Garcidueñas works at the University of Montana in Missoula. As a pathologist, she’s a doctor who looks at the body’s tissues to diagnose disease. She looks for disease caused by pollutant particles that are small — often way too tiny to see. Scientists call these tiny specks particulates. They come from many sources. Power plants, factories, homes and cars — all spew particulates. So can forest fires.

Once inhaled, these particles can move deep into the lungs. The oxygen you breathe passes from the lungs through a thin membrane. From there it enters the blood. Many particulates are small enough to cross that membrane into the blood, too. They’re known as nanoparticulates. They can trigger inflammation wherever they travel. And the blood can carry them everywhere, even to the brain.

Some particulates may enter the brain more directly. If breathed in through the nose, they can contact nerves that bring scent signals to the brain through a structure known as the olfactory bulb. Just as the pollutants’ small size allows them to slip into blood through lung membranes, nanoparticles’ size lets them enter that bulb’s nerve cells. And from there, those inflammatory pollutants can climb into the brain.

Inflammation can be a good thing. The body uses it to kill off damaged cells and harmful germs. But inflammation in the brain is dangerous. It can destroy sensitive cells, causing memory problems.

Digging into the brain

Mexico City, where Calderón-Garcidueñas does her research, is home to nearly 9 million people. Every day, they get around using some 3.5 million cars. And the cars’ exhaust pollutes the air. “High-traffic roads are a very important source of particulate [pollution],” notes Calderón-Garcidueñas.

Research has shown that older adults who live in areas with lots of traffic-related air pollution are more likely to suffer Alzheimer’s disease than are people at cleaner sites. Alzheimer’s causes a type of brain damage that results in memory loss and other problems with thinking, language and behavior.

Alzheimer’s symptoms usually show up in old age. Yet researchers believe the disease may start years — even decades — earlier. Calderon-Garcidueñas wants to know just how early. The answer, she says, might one day help researchers prevent some cases of this memory-robbing disease.

Some elderly dogs can develop brain abnormalities seen in people with Alzheimer’s disease. Waxy clumps of protein, called plaques (PLAKS), may start to litter their brains. But 15 years ago, Calderon-Garcidueñas reported finding these same plaques in the brains of 11-month-old pups! The dogs had been living outdoors, exposed to Mexico City’s heavy air pollution.

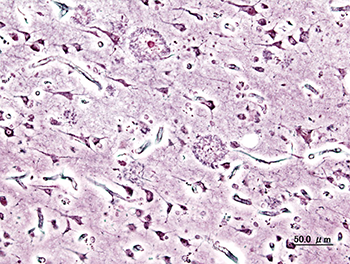

At the time, she told Science News, this is “definitely worrisome.” Even more concerning was her finding of the same type of plaques in the brains of seemingly healthy Mexico City children. The plaques hadn’t caused symptoms. She was only able to find those plaques because of autopsies done on kids who had died in car crashes or other accidents.

But not all children had them. Those living in distant suburbs, breathing cleaner air, had no brain plaques. Air pollution seemed to explain these brain lesions.

Later, Calderon-Garcidueñas showed that teenagers in Mexico City had more problems with memory and attention than did teens in less-polluted cities. We were picking up these problems with attention and thought-processing “that appeared to be linked to high pollution areas,” she said. Her next step was to look at how that might happen. She wondered whether there could be clues in a person’s genetic code.

When pollution conspires with our genes

Today, Calderón-Garcidueñas studies how the genes that some people were born with might combine with air pollution to raise their risk of memory problems, including Alzheimer’s disease. Her work has focused on a gene called APOE. That’s short for apolipoprotein E (AY-poh-lih-poh-PRO-teen E). This gene gives the body instructions for making proteins that help it process the fats in food.

People can be born with any of a few slightly different versions of the gene. Those with the type called APOE 4 have a higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. Calderon-Garcidueñas recently studied children and teens with this version of the gene. Some lived in Mexico City; others in cleaner towns. Of the two groups, those in Mexico City were more likely to have developed the telltale brain plaques. Her team described those findings in the October 2016 Environmental Research.

In a more recent update, Calderon-Garcidueñas’ team found further support for pollution’s link to Alzheimer’s disease. And their latest data are the most disturbing. They viewed the brains of 203 people who had died in Mexico City — from babies (11 months old) to middle-age adults (40 years old). Abnormal proteins that serve as “hallmarks” of Alzheimer’s disease showed up in 99.5 percent of those brains. The researchers conclude that Alzheimer’s disease actually can start in early childhood. And the disease had progressed at a faster pace in those people with the APOE 4 gene.

Details of that work appear in the July 2018 Environmental Research.

“Our findings show that kids need to be protected against air pollution,” says Calderon-Garcidueñas. Most kids can’t control where they live. It might be hard for them to avoid air pollution if they live on a busy road or in a city with lots of cars. That means it’s all the more important to stay away from other substances that can hurt the brain, Calderon-Garcidueñas says. Such things include alcohol, drugs and tobacco. “It’s important to lower the exposures they can control,” she says of kids in polluted communities.

Air pollution is linked to poorer attention

You might not be able to see it or feel it, but air pollution can vary a lot from one day to the next. Such fluctuations could lead to similar day-to-day changes in how a child’s brain functions, says Jordi Sunyer. That’s what his work shows. As an epidemiologist, Sunyer studies the link between pollutants and disease. He coordinates a child health program at the Barcelona Institute for Global Health, ISGlobal. It’s in Barcelona, Spain.

“Attention is critical for school success,” Sunyer points out. It’s the first step in the learning process. Students who are easily distracted will have a harder time focusing on information and remembering it.

“We know there are many factors throughout the day that can cause attention to fluctuate,” Sunyer says. Feeling sleepy can make it harder to stay focused on a task. So can being too hot or too cold. Sunyer had a hunch that air pollution could do this, too.

So his group studied 2,687 children. All were 7 to 10 years old. Each attended one of 39 different Barcelona schools.

Every participant took a computer test four times during the school year. It contained a number of tasks that required paying attention. For instance, one asked kids to watch fish swim in a stream. They were told to click left or right depending on which direction the fish swam. “It’s a simple task, but when kids get bored and lose attention, they start to click the wrong answer,” Sunyer notes.

The researchers also measured levels of air pollution on days that the kids had been tested. Then they compared the kids’ scores when pollution levels in Barcelona had been relatively high or low. And they showed that the kids scored slightly worse on days with higher levels of certain air pollutants. Which types? Nitrogen dioxide and soot (elemental carbon). Both can be spewed by traffic and industrial smokestacks. The researchers shared their results in the March 2017 issue of Epidemiology.

Sunyer now is focused on helping schools in Barcelona identify ways to lower levels of the pollution to which kids are exposed.

For instance, schools could create more zones around them where cars and buses aren’t allowed to idle, meaning run their engines while parked. Another idea: Plant more trees and greenery around schools. Plants can help remove pollutants from the air, Sunyer points out. They do this by absorbing gases and small particles through their leaves and roots.

Air pollution can boost stress hormones

Another reason to control air pollution: It can stress out the body.

Imagine you’re trapped in a room that’s filling with smoke. Your heart is racing. You jump into action. In just seconds, you open the window and climb out the burning building to reach safety. The body’s quick reaction to such an emergency is called the fight-or-flight response.

Scary events, such as a fire, aren’t the only things that can activate that fight-or-flight response. Air pollution can too, new data show. It does so through hormones.

Hormones are the body’s chemical messengers. They control many important activities. Stress hormones help people react quickly to life-threatening situations. When we’re faced with a fearful situation, the body ramps up production of certain hormones, such as adrenaline (Ah-DREN-uh-lin). Breathing polluted air can trigger a similar response, researchers in China now report.

Huichu Li works at Fudan University, in Shanghai. He and his colleagues studied 55 students attending college in that city. Air pollution there is some of the worst in the world. The researchers gave all of these students air purifiers to use in their dormitory rooms. Half received working air purifiers. These helped remove particulates from the air. The other half received real air purifiers that appeared to work — but didn’t. The researchers had removed a filter. Now the devices could no longer remove pollution particles from the air.

The students used the air purifiers for nine days. Afterward, the researchers collected blood and urine from each student. Those with nonworking air purifiers had higher levels of stress hormones in their blood.

In an emergency, stress hormones and the fight-or-flight response can be helpful. But when the body ups their production too often or for too long, those hormones can harm the heart and blood vessels. Fortunately, the students in this test were healthy. None were sickened by their 9-day exposure.

Still, their bodies were “clearly having harmful reactions to the . . . air pollution,” notes Robert Brook. He’s a doctor of internal medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. He was not involved in the study. But Brook can understand its impacts. He has been focusing on how air pollution affects the heart.

Brook worries that repeated short-term exposures to air pollution may add up. “Over many years of exposure, these small health effects might lead to more long-term serious health effects”. After years of exposure, he says, “That could place healthy young people at risk of developing high blood pressure, diabetes or even heart diseases or strokes.”

The Fudan University team published its results last August in the American Heart Association journal Circulation. Future studies, its authors say, should look at whether using air purifiers in homes and buildings might, over time, help protect health.

New studies like the one published by the Fudan team show how far we’ve come in understanding the health effects of air pollution since London’s Great Smog. Yet as in many areas of science, “there’s still a lot to learn,” says Brook. He says one thing is becoming more and more clear: Everyone — even healthy young people — can be harmed by air pollution.