Fighting ‘like an animal’ may not be what you expect

Evolution has produced a broad range of conflict styles

Extravagant headgear on male animals, such as these gemsbok in Namibia’s Etosha National Park, can give species a ferocious look. But nature’s most lethal fighters tend not to be such bulked-up adversaries.

JOHAN SWANEPOEL/SHUTTERSTOCK

By Susan Milius

Pick an animal.

Choose wisely. In this fantasy, you’ll transform into the creature and duel against one of your own. If you care about survival, go for the muscular, multispiked stag roaring at a rival. Never, ever pick the wingless male fig wasp. Way too dangerous!

This advice sounds exactly wrong. But that’s because many stereotypes of animal conflict get the biology backward. All-out fighting to the death is the rule only for certain specialized creatures. Whether a species is bigger than a breadbox has little to do with deadly ferocity.

Many creatures that routinely kill their own kind would be terrifying — if they were larger than a jelly bean. Certain male fig wasps unable to leave the fruit they hatch in have become textbook examples, notes Mark Briffa. He studies animal combat at Plymouth University in England. Stranded for life in one fig, these males grow “big mouthparts like a pair of scissors,” he says. They use those mouthparts to “decapitate as many other males as they possibly can.” The last he-wasp crawling has no competition to mate with all the females in his own private fruit palace.

In contrast, some of the big mammals that inspire sports-team mascots use their antlers, horns and other outsize male weaponry for posing, feinting and strength testing. Duels to the death are rare among these species.

“In the vast majority of cases, what we think of as fights are solved without any injuries at all,” says Briffa.

Evolution has produced a full rainbow of conflict styles. They range from the routine killers to animals that never touch an adversary. Working out how various species in that spectrum assess when it’s worth their while to go head-to-head has become a challenging research puzzle.

To untangle the rules of engagement, researchers are turning to animals that live large in small bodies and have no sports teams named after them. At least not yet.

Story continues below video.

Deadliest matches

It’s hard to imagine nematodes fighting at all. There’s little, if any, weaponry visible on their see-through, micronoodle bodies. And that includes the species called Steinernema longicaudum (STYN-er-NEE-muh Lon-jih-KAW-dum). Yet in Christine Griffin’s lab, a graduate student offered a rare hermaphrodite to a male as a possible mate. (A hermaphrodite is an individual with the traits of both a male and female.) Instead of mating, the actual male went in for the kill.

“We thought, well, poor hermaphrodite. She’s not used to mating. So maybe it’s just some kind of accident,” says Griffin. (Griffin’s lab at Maynooth University in Ireland specializes in nematodes as pest control for insects.) The grad student, Kathryn O’Callaghan, also offered females of another species to the males. The males killed some of those females too. When given a chance, males also readily killed each other. That’s how nematodes, in 2014, joined the list of kill-your-own-kind animals, Griffin says.

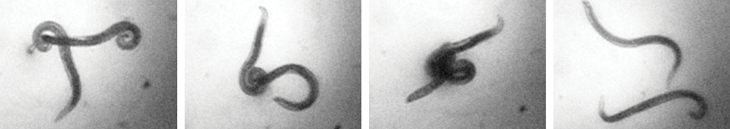

Killing another nematode is an accomplishment for a skinny thread of an animal with just two thin, protruding prongs. The male S. longicaudum slays by putting his mating moves to new uses.

When he encounters a female of his own species, the male coils his tail around her. He then moves the prongs — known as spicules — that are used to hold open the entrance to her reproductive tract. To kill, a male just coils his tail around another male (or a female of a different species) and squeezes extra hard. Pressure ruptures internal organs. Sometimes those spicules even punch a hole during this fatal embrace. The grip lasts from a few seconds to several minutes. Of those worms paralyzed by the attack, most are dead the next day.

Other nematodes live in labs around the world without murdering each other. So why does S. longicaudum lean toward extreme violence? Its lifestyle of making a home inside an insect inclines it to kill, Griffin suggests. An insect larva is a prize that one male worm can monopolize. It’s also the only place he can mate.

These nematodes lurk in soil without reproducing or even feeding until they find a promising target, such as the pale fat larva of a black vine weevil. Nematodes wriggle in through any opening — the larva’s mouth, its breathing pores or maybe its anus. If a male kills all male rivals inside his new home, he can start a huge family tree with lots of generations of offspring. Those offspring might total in the hundreds of thousands, Griffin points out.

Territorial female slayers

A defendable bonanza like a weevil larva, or a fig, has become a theme in the evolution of deadly fighting. Biologists have studied violence in certain male fig wasps for decades. However, more recent research has revealed that some females kill each other, too.

A female Pegoscapus (Pay-go-SKAY-pus) wasp is a bit longer than a poppy seed. When she chooses one particular pea-sized sac of flowers — a fig-to-be — she’s deciding her destiny. That sac is most likely her only chance at laying eggs. And it will probably be the fruit she will die in, notes Charlotte Jandér. She’s an evolutionary ecologist at Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass.

Shortleaf fig trees have “a delicate flowery smell,” Jandér says. The blooms, though, are hidden inside little green-skinned sacs. To reach these inner riches and lay one egg per flower in as many flowers as she can, the wasp must push through a tight tunnel. The squeeze can take roughly half an hour. And it could rip her wings and antennae. Reaching the inner cavity carpeted in whitish flowers, “there is plenty of space for one wasp to move around,” Jandér says. But more than one gets cramped, and conflicts get desperate.

In a wasp species from Panama that Jandér has watched, females “can lock on to each other’s jaws for hours and push back and forth,” she says. In a Brazilian species, 31 females were found decapitated among 84 wasps. Jandér was part of a research team that reported this in 2015. It was the first documented female-to-female killing in fig wasps.

Walk away

Many animal species have ways to back off rather than fight to the death. Briffa studies one example: sea anemones. And yes, anemones fight.

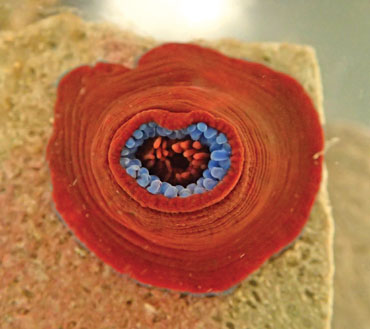

The formal name for beadlet sea anemones is Actinia equine (Ak-TIN-ee-uh E-KWY-nuh). They release their sperm and eggs into open seawater. The animals don’t need to argue over mates. For a prime bit of tide-pool rock, however, tensions may rise.

Below a beadlet’s pinkish, swaying food-catcher tentacles are what often look like “little blue beads,” Briffa points out. These are fighting tentacles, or acrorhagi (AA-kroh-RAJ-ee). When combat looms, the anemone inflates them. “Imagine someone pulling out their bottom lip to make a funny face,” he says.

It’s no joke for an impertinent neighbor. Anemones are distant relatives of stinging jellies. And their acrorhagi carry harpoon-shooting, toxin-injecting capsules. Combatants rake stinger acrorhagi down each other’s soft flesh. “It almost looks like they’re punching each other,” Briffa says. “When one of the anemones decides it’s had enough and wants to quit the contest, it actually actively walks away.”

“Walk” is used loosely here, notes Sarah Lane. Then she demonstrates by alternately arching her hand and flattening it in a measured trip across the Skype screen. She’s a postdoc in Briffa’s lab. Maybe it moves “like a cartoon caterpillar?” she says, trying to describe the gait. Or perhaps “a concertina?”

To start fights, the researchers place anenomes side by side in the lab. About one time in every three the anemones concertina away or otherwise resolve the tension without any acrorhagi swipes. Backing down this way makes sense considering that a full exchange “looks quite vicious,” Lane says. Strikes leave behind bluish fragments of acrorhagi full of stinging capsules. Those capsules kill tissue on the recipient.

The attacker won’t leave unscathed either. Close-ups show open wounds where acrorhagi tissue was pulled out. An anemone “literally can’t hurt an opponent without ripping parts of itself off,” she explains.

Injuries to an attacker from swiping, biting or other acts of aggression get overlooked in discussing how animals weigh the costs and benefits of dueling. Lane and Briffa argued this in the April 2017 Animal Behaviour. The sea anemones may be an extreme example of self-harm from a strike. Still, they’re not the only one.

Humans can hurt themselves when they attack. Deciding whether to fight can have some unintended impacts, Lane points out. In a bare-handed punch at somebody’s head, little bones in the hand crack — creating so-called boxer’s fractures — before the skull cracks. With the introduction of gloves around 1897, boxer’s fractures basically disappeared from match records, Lane says. Before gloves, however, records show no reported deaths in professional matches. Once gloves lessened the costs of delivering high-impact punches, deaths began appearing in the records.

Worth the fight?

Sea anemones don’t have a brain or central nervous system. However, costs and benefits of fighting somehow still matter. The animals clearly pick their fights. They escalate some blobby sting matches and creep away from others.

Just how anemones choose — or how any animal chooses — when to fight and when to back down turns out to be a rich vein for research. Scientists have proposed versions of two basic approaches. One is called mutual assessment. This “is sussing out when you’re weaker and giving up as soon as you know,” Briffa says. “That’s the smart way.” Yet the evidence Briffa has so far, he says with perhaps a touch of wistfulness, suggests anemones use “the dumb way of giving up.”

This “dumb” option is called self-assessment. Animals resort to this when they can’t compare their opponent’s odds of winning with their own. Maybe they fight in shadowy, murky places. Maybe they don’t have the neural “smarts” for that type of comparison. For whatever reason, they’re stuck with “keep going until you can’t keep going anymore,” he says. Never mind if the fight is hopeless from the beginning.

The odds of fighting “smart” look better for the animals that Patrick Green of Duke University in Durham, N.C., studies. These creatures have a brainlike ganglion (GANG-lee-un). And they come close to fighting with superpowers. He’s working with, of course, mantis shrimp.

The high-powered smashers among these small crustaceans flick out a club to move at “highway speeds,” Green says. What’s more remarkable is that the club reaches those speeds really fast. They accelerate like a bullet shooting out of a .22 caliber pistol.

When the clubs wham a tasty snail, the bounce back creates a low-pressure zone that vaporizes water. “I always feel weird saying this because it seems just goofy.” Still, Green says, “that does release heat equivalent to the surface of the sun.” Fortunatey, it lasts only a fraction of a microsecond.

When smasher mantis shrimp — males or females — fight each other, they batter rivals into oblivion. The reality, though, is arguably stranger. They superpunch each other. But the blows land on an area that can withstand the force. It’s the telson. This bumpy shield covers the rump.

In Caribbean rock mantis shrimp, the battle is often over after just one to five blows. Those blows happen too fast for the human eye to see. In test fights between animals of equal size, the winner is not the animal that lands the most forceful blow. Instead, it’s the one that gets in the most punches. Then, with no visible gore, one dueler just gives up.

Story continues below image.

Green and Sheila Patek, also at Duke, propose that this telson sparring permits genuine mutual assessment. That’s the smart way of losing a fight. It’s difficult to figure out what lurks in the neural circuits of an arthropod. However, the researchers presented multiple lines of evidence in the January 31 Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

One strong clue came from matches that Green staged between mantis shrimp of different sizes. He didn’t see a trend of smaller ones pointlessly pounding telsons as the lightweights fought bigger animals. Those bigger animals were going to win anyway. And it seemed as if the smaller ones understood that. This suggests something more than self-assessment is going on, Green and Patek now propose.

Researchers think they have seen mutual assessment in other animals too. These include wrestling male New Zealand giraffe weevils. They’ve also seen it in male jumping spiders that flip up banded legs in “Goal!” position to intimidate rivals. Analyzing assessment gets tricky.

For instance, scientists, dazzled by the sights and sounds that our own sensory world emphasizes, may be underestimating chemical cues. Among crawfish, “part of their fight is squirting urine in one another’s faces,” Briffa says.

Paradoxically peaceful

Many of the scariest-looking weapons end up causing little bodily harm. Some are specialized for combat that’s more strategic than gory. Other weapons look so scary they hardly ever get used.

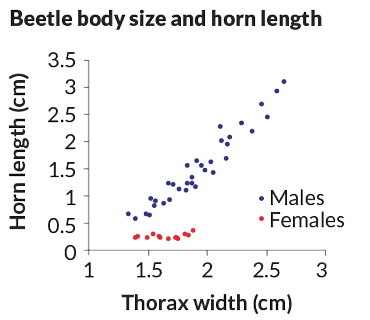

Erin McCulloughan is an evolutionary biologist, now working at the University of Western Australia in Perth. The male Asian rhinoceros beetles that she studies host odd horns. The forked horns on their heads stretch nearly two-thirds the beetle’s body length. Surprisingly lightweight, the horns look cumbersome. They resemble “a Styrofoam leg sticking out of your forehead,” she says.

She watched the guys compete furiously with each one night at a university in Taiwan. Despite it being hot and muggy, her shirts had the collars pulled way up. Leather gloves covered her hands. She hardly blended in with the students. So why all this gear? “You shouldn’t wear mosquito repellant when you’re working with insects,” she explains.

But it was worth it. The scene illuminated by her head lamp was “really messy and chaotic,” she recalls. Beetles flying out of the dark fought to dominate cracks in ash tree bark that oozed sap and attracted females. A dominant beetle would grip the bark and use his horn to flick incoming challengers off the branch left and right — until some other guy unseated him. Getting thrown off the limb doesn’t kill losers. Often they buzz right back for another try.

Yet from the vantage point of evolution, a male who doesn’t mate might as well be dead. His genes will never be carried on to the next generation. That meant his winning a female has important impacts for his community impacts. Males with longer horns are better at flicking off other males. Yet longer horns also are more likely to snap, McCullough notes. And a broken horn won’t grow back.

The extravagant tool needs to be a pry bar of just the right length, lightness and strength. Fresh, new horns on male beetles just starting their fighting careers have about four times the strength the horns need to resist cracking. (That’s about the safety factor that engineers build into bridges but less than the standard for elevator cables, she notes.)

Horns or antlers on male mammals often can kill. Yet fatal fights may be rare, says Douglas Emlen. He’s a biologist at the University of Montana in Missoula. One of his favorite studies comes from decades-old research on caribou. That study looked at about 1,308 sparring matches between male caribou in Alaska. With all this glaring, snorting and rushing, only six matches escalated into violent, bloody fights.

Evolution usually does not favor extremes in teeth, horns or other such body weaponry. Certain forms of rivalry for mates, however, can foster certain weapons to expand extravagantly in a body-part arms race. There are common patterns to such arms races, Emlen says, including some cheating.

Among conditions that favor an arms race are rivalries playing out in one-on-one duels, he says. Imagine a magnificently endowed dung beetle in a tunnel. He guards a female in the depths behind him. One by one, he must fend off all rivals for her attention. Growing bigger and bigger horns, however, comes with a cost. Eventually, only an animal with the best nutrition, genes and luck can spare the resources to grow a truly commanding horn. And at this point, horn size signals a male that can overpower just about all rivals. Only another supermale will engage him in an all out fight. The rest of the time, his threatening weaponry keeps the peace with barely a bump or a bruise.

Yet this is “a very unstable situation,” Emlen adds. “It creates incentives for males to cheat.” Or maybe the word should be “innovate.” He has found that big-horned male dung beetles defending their tunnels can be outmaneuvered by small rivals. Those smaller beetles dug bypass tunnels around the guard zone. That let them mate with the supposedly defended female.

At the far extreme of animal rivalries are some species that blur the meaning of fights. Some butterflies, such as the speckled wood butterfly, “fight” without physical contact. Males compete for a little sunlit dapple on the forest floor by flying furious circles around each other until one gives up and scrams. No gore, but probably really exhausting.