Worms in the gut keep mice from getting plump on high-fat food

The intestinal parasites also changed how food affected their host's immune system

This round worm, Heligmosomoides polygyrus, was retrieved from the gut of a wood mouse. New research shows that being infected by such parasites can keep animals from gaining weight, even when eating fattening food.

Naldo-Crocoduck/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

As a man walks barefoot outdoors, unknowingly his feet encounter very tiny worms. Secretly, one or more of the parasites crawl onto his skin — and then through it. Once inside, these hookworms move around until they end up in their victim’s gut. They latch onto their host’s intestines and from there feast on his blood.

This is not the script for some horror movie. It’s what has already happened to roughly one in every four people on Earth. That’s some 1.9 billion people. But a new study in rodents suggests that hosting these hookworms may have some upsides: weight control and a healthier immune system.

Let’s not downplay the fact that hookworms can bring misery. They eat some of their hosts’ blood, leaving them with lower levels of iron. This may make it hard for the bloodstream to carry a normal load of oxygen through the body, a condition known as anemia (Uh-NEE-mee-uh). The worms also can cause painful rashes and stunt a child’s growth and development. Few doctors, then, would ever prescribe the worms to their patients. But the new data do point to how mammals may have evolved to deal with — indeed, accommodate — some common, nasty infections. And people have had a long time to deal with hookworms. Even ancient mummies show signs of being infected.

During the last century, though, hookworm infections have become rare in developed countries, such as the United States.

In countries that are not so industrialized, “there are lots of infectious diseases, including worm infections,” notes Haining Shi. He studies diseases in children at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Mass. People who live in such countries, he adds, also have lower rates of certain chronic (long-term) diseases than do folks in industrial nations. This prompted Shi’s team to test an idea: Might parasites help prevent some serious, chronic ailments?

The group decided to focus on obesity. One third of U.S. adults are obese. Nearly one in every six children also are overweight or obese. Carrying too much body fat can lead to a host of other serious health problems, including heart disease and type 2 diabetes.

Obesity comes from consuming more energy, in the form of food, than the body uses. But not all bodies use energy with the same efficiency. And Shi’s team now shows that parasitic worms change how efficiently a body uses energy — at least in mice.

How they found this out

The researchers chose mice as a model for what might be expected to occur in people. Like people, mice that eat high-fat foods tend to get fat. These animals also can host parasitic worms. The parasite that Shi chose to work with, Heligmosomoides polygyrus (Heh-LIG-moh-soh-MOY-ih-dees Pah-lee-GY-rus), is not a hookworm. And it does not live in people. But hookworms are a type of nematode (NEE-muh-toad). And this worm is a nematode similar to the hookworms that infect people.

The scientists divided mice into four groups. Two groups were fed a normal diet. The rest ate high-fat chow. The researchers infected one group of mice on each of the two diets with nematode larvae. Shi’s group then measured the animals’ growth for up to 105 days.

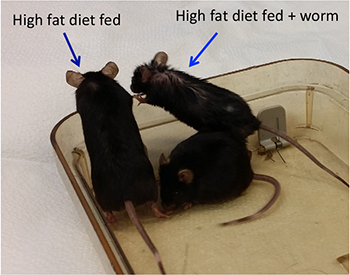

The noninfected mice eating the high-fat food nearly doubled in size. But they were the only group to do so. All animals on the regular food grew at the normal rate. So did worm-infected mice eating the high-fat food.

If the weight loss happened because infected mice were losing blood to the worms, why didn’t those on a normal diet lose weight compared to the uninfected mice? The answer, Shi’s group showed, was a bit complicated. The worms changed how the infected mice processed high-fat meals.

When uninfected mice fattened up, their blood sugar rose. So did blood levels of fatty materials, such as cholesterol (Koh-LES-tur-awl) and triglycerides (Try-GLIH-sur-eydz). Even their livers got fattier. And that wasn’t all. Different fat-related genes turned on in these animals.

No mouse eating a normal diet showed such changes. Neither did the worm-infected mice eating high fat meals.

Worms even affected what type of fat was stored. Like humans, mice have two types. White fat is an energy-rich type that can be burned at some future date. Think of it as fuel stored in the body’s pantries. Brown fat is enriched with a special molecule known as an uncoupling protein. This protein turns on the body’s energy-burning machinery.

The obese mice had mostly white fat. Wormy rodents that ate the high-fat diet had bonus brown fat.

Indeed, Shi now reports, “We found that the worm has a beneficial effect” — especially in mice eating a fatty diet. His team published its results online March 15 in Scientific Reports.

What was behind all of these changes?

How could worms alter blood, livers, gene activity and brown-fat levels? Shi now suspects that cells in the immune system drove these changes.

Other studies had shown that parasitic worms can act on several specific cells. Shi tested one type of immune cell known as a macrophage (MAK-roh-fayj).

These are big cells. They eat viruses and bacteria — germs that can make a person sick. They also can trigger inflammation. You may have noticed one type of inflammation in your own body. When a cut or scrape becomes infected, it becomes red, swollen and hot. This inflammation is one way that the immune system fights infections. But chronic (long-term) inflammation is not healthy. And low-grade, long-term inflammation is seen in animals and people that are obese.

Animals get obese as they produce more white fat. This fat collects macrophages. There are different types. The M1 type triggers inflammation. M2 macrophages shut down inflammation. Fat mice without worms had more M1 macrophages. Wormy mice had more of the M2 type.

The researchers thought that the M2 macrophage might be the key to how worm infections altered the mice. To test this, they transferred macrophages from mice with and without the worms into noninfected obese mice.

These fat mice getting macrophages from mice without worms kept gaining a lot of weight. But those that got macrophages from worm-infected mice gained less. They also had healthier blood levels of sugar, fat and cholesterol. They even had more decoupling proteins in their fat, making it browner.

Shi’s team now concludes that hosting worms changed how mice processed high-fat diets just by changing their macrophages.

The researchers had previously shown that parasitic worms affect which microbes live in mouse guts (microbes live in all mammals’ guts). Other researchers found that worms protect mice from different diseases caused by a faulty immune system. Marc Hübner is one of these scientists.

Hübner studies how parasites affect diabetes. He works at the Institute for Medical Microbiology in Bonn, Germany. The Harvard team’s study confirms what scientists suspected about how worms change mice, he says. He adds that as such studies go, “this is a really good [one].”

Shi cautions that there are always two sides to a story. It’s good that worms can lower chronic inflammation. But what happens when someone with a parasite also encounters a germ that causes disease? Shi suspects that their immune system won’t be able to fight the new infection very well. Parasitic worms might therefore make other common infections more dangerous. This, he says, is a big problem for children with worms.

“In humans, we still have some work to do,” says Shi. “We see that the worm is really important and beneficial. But in reality … nobody will take a live worm.” He hopes to find out more about how worms change the immune system. Then, scientists may be able to figure out how to treat people in such a way that they get those benefits without having to become infected with the worms.