This extinct bird boasted dinosaur-like teeth

Reconstructing the bird's skull offers new clues to bird evolution

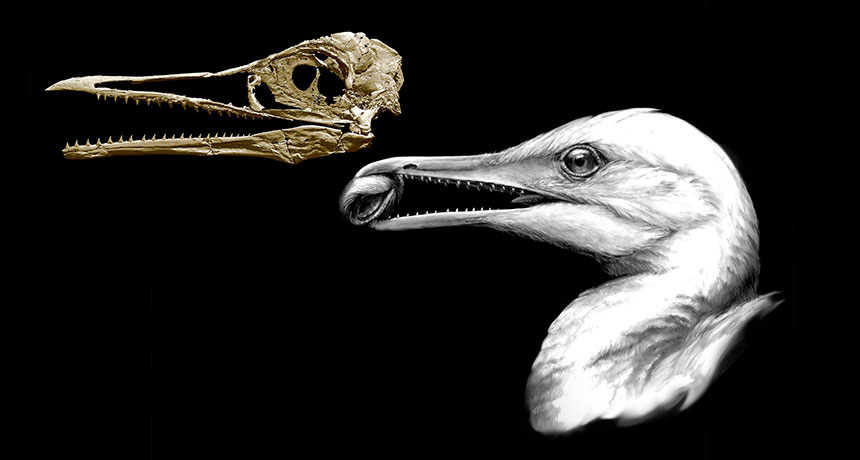

Scientists used fossils of an ancient toothed bird (illustrated at right) to make a 3-D reconstruction of its skull (left). They discovered the animal had a small beak at the tip of its snout.

Michael Hanson and B.-A. Bhullar

A bird that lived alongside dinosaurs may have used its beak to preen its feathers, as modern birds do. But it also had a full mouth of teeth. These let it chew like a dino. The finding provides new clues to how birds evolved from dinosaurs.

Scientists made a new 3-D reconstruction of the skull of Ichthyornis (Ick-thee-OR-nis) dispar. This bird lived during the Late Cretaceous, some 87 million to 82 million years ago. The new reconstruction shows this creature had a small, primitive beak. Its upper jaw would have moved around easily. Such traits would have let the bird use its beak to precisely groom itself and grab things, much as modern birds do. But I. dispar also kept some features from its dino ancestors. These included teeth and strong jaw muscles.

This ancient bird shows up often in textbooks. Paleontologist Othniel C. Marsh first described the animal some 150 years ago. It was a water bird, similar to a tern. Much like a duck, its wings spanned about 60 centimeters (24 inches). The shape of those wings and its breastbone suggested this bird could fly.

Another famous fossil flyer is Archaeopteryx (Ar-kee-OP-tur-ix). This extinct reptile lived about 70 million years before I. dispar. Archaeopteryx had a more reptilian skull, notes Bhart-Anjan Bhullar. He’s a vertebrate paleontologist at Yale University in New Haven, Conn. With a beak and fairly large head, the skull of I. dispar much better resembles those in modern birds, he says.

Several skulls of I. dispar existed at various museums. Still, there was much science didn’t know about these birds, Bhullar says. One reason: Fossils dug up in the 19th century had been smashed flat in places. This made it hard to see a lot of important details. Then, in 2014, researchers unearthed a new I. dispar fossil. It contained a nearly perfect skull.

The researchers combined that fossil with three partial skulls from museum collections. They also took a closer look at the skull found 150 years ago. Bhullar’s team input details from all of these skulls into a computer. It helped to recreate a 3-D image of what the ancient bird would have looked like. Those researchers published it May 3 in Nature.

An in-between head

The reconstruction showed these birds could raise their upper jaw separately from the lower jaw, as modern birds can. This range of motion would have let I. dispar use its tiny beak like tweezers to peck or preen or grasp objects. Large holes in the sides of its skull show where jaw muscles attached. The size of those holes suggests those muscles would have been strong. Says Bhullar, this suggests that “it was pecking like a bird and biting down like a dino.”

His team also made detailed measurements of the inside of the skull. This showed them the brain’s shape. And again, in many ways it looked like those of modern birds.

For example, the forebrain is an area in the front related to thinking. In I. dispar it was large. This brain also had big optic lobes — regions that process images sent from the eyes. “This [creature] was thinking like a bird, and had sensitive vision and motor coordination,” Bhullar concludes. It might have needed these traits to handle the intense physical challenges of flying.

The new study offers the first in-depth look at the skull of this ancient species, says Lawrence Witmer, who was not part of the new study. This vertebrate paleontologist at Ohio University in Athens says the study gives important new details on how dino jaws morphed into today’s bird beaks. Dinosaur jaws were toothy and covered in skin. A modern bird’s beak lacks teeth and is covered in keratin, the same stuff from which human hair is made.

Luis Chiappe praises the careful way researchers studied this important historical fossil. Chiappe, too, is a vertebrate paleontologist. He works at the Natural History Museum in Los Angeles, Calif. Still, he is not convinced that the size of the brain and other traits are related to the bird’s flying ability. He’s also not sure that I. dispar’s in-between features offer general clues to the way all birds would have evolved from dinosaurs.

“We have big questions about what was happening with birds in the Late Cretaceous,” he says. Scientists don’t know much about these animals’ skulls. “It could be that what we see in Ichthyornis might not be representative of an evolutionary trend,” he says.