Climate change intensified Hurricane Florence, study finds

It concluded that the storm’s size and fury would have been much smaller without global warming

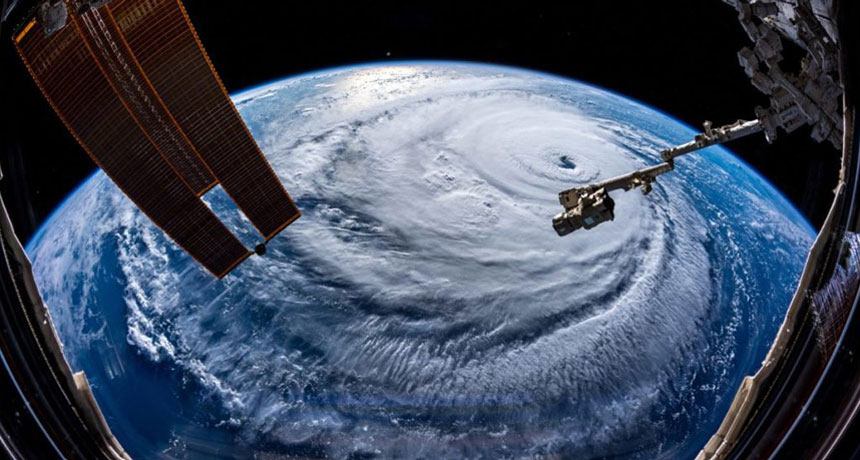

Florence was captured by cameras aboard the International Space Station on September 12. The storm was so big that scientists had to use a super wide-angle camera to see it all.

NASA

Scientists recently completed a compelling experiment. They knew Hurricane Florence was barreling towards the United States’ East Coast. It was whipping up ferocious winds and the potential to drop enough rain to flood huge swaths of land. A warming climate can provoke more severe weather events. So this team decided to probe whether Earth’s climate fever might have intensified Florence. And their study’s finding: It did!

Kevin Reed is a climate scientist at Stony Brook University in New York. His work focuses on modeling climate. His team feeds data into a computer program that forecasts the weather. The researchers instruct this computer model to alter any of many features of Earth’s atmosphere (heat, winds, moisture, pressure readings and more), then look at how these changes altered forecasts of how weather events would play out in the near future.

And that’s what Reed’s team did for Florence.

This showed that Florence would end up being bigger than it would have been if it occurred in a world with no human-caused warming. A warmer sea surface and more available moisture in the air — both due to climate change — also point to Florence dumping 50 percent more rain on parts of the states of North and South Carolina.

The researchers described how they reached these assessments in a September 12 report posted on Stony Brook University’s website.

Such studies fall into a relatively new field known as attribution science. These studies investigate whether the intensity of some weather event — such as a hurricane, heat wave or flood — can be linked to certain particular conditions. Attribution science has been gaining increasing interest and respect. That became especially true after three studies last year found that a trio of extreme events in 2016 simply could not have happened without climate change.

The goal of the new study was to calculate whether, and by how much, human-driven climate change altered Florence.

To do that, Reed’s team considered: What would happen if, from a single starting point — in this case, the state of the atmosphere on September 11 — Florence roared ahead in two parallel worlds? In one of them, it lived within the context of human-caused climate change. In the other, it was affected only by conditions that would have existed before climate change

Until now, such studies have been conducted only long after an event is over. Reed’s group got a jump on answering the question. They performed the first attribution study for an extreme event that was still in progress.

It’s not yet clear what role such real-time attribution studies might play in society. Will they one day aid emergency planning? Might they change the course of how governments set policies for their community’s growth? Might such studies even affect lawsuits by people impacted by extreme, climate-fueled events?

For now, what this study reveals is that “dangerous climate change is here,” says Michael Wehner. He’s a climate scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California. He also was an author of the new study. The new analysis suggests that the chances of experiencing an extreme event and the degree of danger it poses “have already been significantly increased.”

Reed talked with Science News about what attribution studies are and what this one suggests about the likely impact of climate change on Florence. His responses have been edited for space and clarity.

SN: We’ve heard many times that scientists can’t say whether a particular storm was caused by climate change. How is this different?

Reed: We’re not making a statement about whether this storm is more likely due to climate change. That’s not something we can do. We’re doing forecasts of an existing storm — looking at the impacts of climate change on this storm that’s already occurring.

SN: So how does that work?

Reed: It’s relatively simple. What we did was basically take a [computer] model that’s traditionally used for climate forecasting and changed it to operate like a weather model.

We started with the state of the atmosphere as it was on September 11. We run a set of weather forecasts, or ensembles, [that forecast out to] seven days. Then we go back to those initial conditions and remove the signature of climate change.

SN: You describe doing that as if Hurricane Florence were to occur in a world without human-induced global warming. How do you create that world?

Reed: We use climate simulations created by an international project (called C20C+) that model the climate with and without human-created greenhouse gases over the last 100-plus years. That creates a climate change signal that we can remove from our initial conditions of the forecast.

SN: So you ran these two scenarios to see how climate change has changed Florence’s fate. What did you find?

Reed: We see increased rainfall [due to climate change]. In the areas of heaviest [rains], for example, the ensembles with the climate-change signal show that rainfall is heavier by more than 50 percent.

We also looked at the size of the storm. The forecasted diameter of Florence is about 80 kilometers [50 miles] wider than without climate change. That means that higher winds are being felt by a larger area.

The size of the storm is important for things like storm surge: A larger storm can produce larger storm surge, as more winds push more water toward the shore.

Story continues below video.

SN: The forecasts for Florence have changed a lot since you set your initial conditions on September 11. The projected track has moved southward. And we now think the storm will stall over the Carolinas. What does that mean for your results?

Reed: Yeah, [the stalling] wasn’t a thing a few days ago. So the forecasts are less accurate than they would have been with more recent data. But to see the signal of climate change in what happened to the storm, we basically just wanted to compare apples to apples. That’s the essence of what we’re doing here: running this attribution study along with the forecasts.

SN: Are you updating it as you go?

Reed: We are going in and doing additional runs every day, with new conditions. We won’t really be able to do an in-depth analysis until the storm is done. It’s very experimental right now, but we’re getting ideas for how it can be applied in the future.

SN: Doing a climate-attribution study for an event while it’s still happening seems potentially controversial. Have you gotten pushback from other scientists?

Reed: [Laughs] Yes, other scientists have reached out to ask about how we set up things. And everybody has their opinions of how we do these types of things. We think we’ve done it right, but we put it out there and everybody has their chance to [now comment]. It’s the scientific process.