Microplastics take flight in the bellies of mosquitoes

The pollution stays in these insects as they grow from larvae to adults, putting birds at risk

Mosquitoes start their lives as larvae that live in water. They chow down on algae and bacteria — and tiny bits of plastic, if they happen to be around.

ApisitWilaijit/istockphoto

Microplastics have become a common type of water pollutant. And these pollutants can now become airborne in the bellies of mosquitoes, a new study shows.

Researchers in the United Kingdom recently found that mosquito larvae can eat tiny bits of plastic from the water in which they’re living. As the mosquitoes grow into adults, much of that plastic stays inside them. That means birds and bats that eat mosquitoes may be taking in a mouthful of plastic with every meal. And any other animal that eats those birds and bats is probably also getting a little microplastic with their meals.

“We don’t yet know how harmful the microplastics will be,” says Amanda Callaghan. However, she adds, “If we wait to find out, it may be too late to do anything about it.” Callaghan is a zoologist who works at the University of Reading in England. Her team’s new findings appeared in the September Biology Letters.

Munching on microplastics

Microplastics are any bits of plastic smaller than half a centimeter (0.2 inch) across. In recent years, scientists have been finding these plastic bits in water all over the world. They tend to enter rivers as wastewater pollutants. From those rivers, they can drain into lakes and the ocean. Affected water can include sites where mosquitoes lay their eggs.

To find out what effects this might have, a member of Callaghan’s team, Rana Al-Jaibachi, fed microplastics to mosquito larvae in the lab. Larvae are the worm-like young of certain insects. Larvae often are adapted to survive very different environments than those they’ll live in as adults. Adult mosquitoes live in the air, for instance. Their larvae, however, hang out in small pockets of still water. There they gobble up algae and bacteria that live on the water’s surface.

In the lab, Al-Jaibachi put ground-up guinea pig food in the water where the larvae were growing. She added tiny beads of plastic. In total, she gave microplastic beads to 150 larvae.

To find out whether the larvae had gobbled up any microplastic, she randomly chose 15 larvae to examine. She selected 15 more mosquitoes after they’d grown into adults. Next she counted the number of beads in each insect.

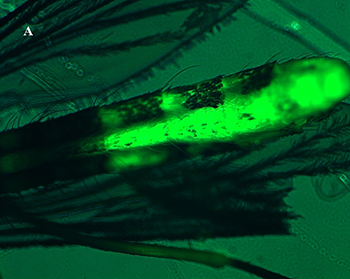

“We counted the beads by grinding up the mosquito, filtering out the beads and looking down a microscope,” explains Callaghan. The plastic particles were too small to be ground up along with the animals’ tissue. And the beads were fluorescent, so they glowed green under blue light.

Microplastics showed up in all 30 mosquitoes, both larvae and adults. But the larvae hosted more of them. On average, each larva held more than 3,000 2-micrometer-wide beads. (A micrometer is one ten-thousandth of a centimeter.) The adults only had about 40 beads each. The researchers now suspect the mosquitoes may pee out some microplastics as they grow up.

Callaghan says the lesson from her team’s study is that microplastics are everywhere. “They can even move up into the air if they are eaten by an animal that can fly,” she concludes.

Marcus Eriksen is an environmental scientist at the 5 Gyres Institute in Los Angeles, Calif. There, he studies plastic pollution in oceans and lakes. And he would like to know how microplastics move through the environment outside of the lab.

The study by Callaghan’s team is helpful, he says, because it shows microplastic can stay in the bodies of mosquitoes as they grow into adults. “Now it’s time to move to a real population of mosquitoes in nature and real quantities of plastic in the environment,” he says. “If we see an effect, then we’ve got something to act on.”

Cause for concern

How might mosquito larvae end up gobbling plastic in the wild? There are many ways microplastics can get into the lakes, ponds and puddles where mosquitoes lay their eggs. Some bits come from larger pieces of plastic that can break down in landfills and large bodies of water. Sunlight and waves help break these pieces into tiny bits.

Some clothing can shed microplastics, too. Fabrics such as fleece and nylon are made from plastic. When washed, they release bits of plastic lint into the wash water. This lint can then travel down household drains and into rivers, lakes and oceans.

Some companies also add tiny plastic beads to toothpastes and skin-care products. These beads help scrub away tooth plaque and dead skin cells. Then they, too, wash down the drain.

Plastics are made from many different chemical ingredients. Scientists still don’t know how many of these ingredients might affect human health. Plastics can also act like a chemical sponge, soaking up other pollutants from the water around it. For example, pesticides and other toxic compounds have turned up in plastics floating in water.

Callaghan’s study is concerning because it shows we can’t escape microplastics, says Kennedy Bucci. She is a PhD student in Canada at the University of Toronto. She studies how microplastic pollution affects freshwater organisms.

“We already know that microplastics are found in our oceans, lakes, rivers, agricultural fields and soil,” she says. “But now this study suggests that they can also be found in our skies.”