This rewritable paper depends on disappearing ink

Words and pictures last at least six months and can be rewritten and erased up to 100 times

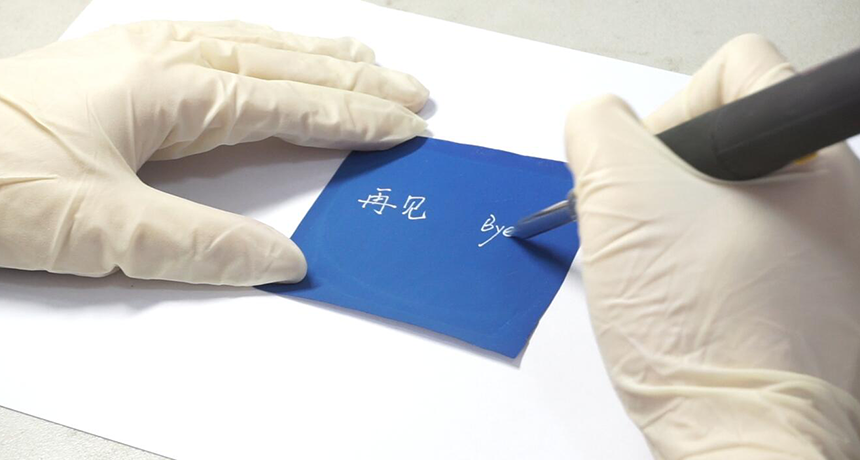

A special pen heats the blue ink on this rewritable paper. As the ink warms, it turns clear. The white paper beneath reveals a written message.

Luzhuo Chen

Have you ever made a mistake while you were trying to print from a computer? That paper probably went right into the recycling bin. From there, it was taken to a waste-handling plant to eventually be broken down and remade. But what if you simply could erase your mistake and reuse that first sheet of paper? That option may become available, thanks to a new technology.

It’s a novel type of rewritable paper that can be used more than 100 times. Words and pictures remain visible on it for at least half a year. This is hardly the first rewritable paper. But the marks on those earlier versions tended to fade away in less than three months.

Luzhuo Chen is a physicist at Fujian Normal University in Fuzhou, China. He led the group that made the new rewritable paper. His team was inspired by pens that contain erasable ink. That ink disappears when heated. To erase your writing, you rub the pen’s special eraser against the paper. Rubbing warms the paper and ink, making its message go away. But if the ink gets cold enough, the writing returns. So to reveal the erased message, just put that paper in the freezer.

To make its new rewritable paper, Chen’s group switched the ink from the pen to the paper. They covered one side of regular printer paper with the ink used in those erasable pens. Using a heated pen or printer, they can now write or print on this paper. That warmth makes the ink disappear.

This is the opposite of how writing usually works, where ink is applied to paper. With the new system, the spots where you write become white instead of colored because that heat makes the ink covering the white paper disappear. Imagine painting on a piece of blue construction paper with white paint. This is what writing on the new paper looks like.

Chen’s team described its new rewritable paper November 8 in ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces.

How the ink works

The ink used to print on the new paper appears and disappears because of something called a redox reaction. The term is a combination of reduction and oxidation. Reduction describes a chemical reaction whereby a molecule gains an electron. In oxidation, a molecule loses an electron.

The ink Chen’s group used forms its color with a material known as crystal violet lactone. It also relies on a color developer called bisphenol A (BPA). The color-forming agent needs the developer to steal an electron from — or oxidize — it.

The ink also contains a solvent. The researchers could not find out what’s in the solvent because it’s a trade secret protected by the company that makes the ink. But they think it’s made of aliphatic (Al-ih-FAA-tik) esters or aliphatic carboxylic (Kar-box-IL-ik) acids. Only when the color-forming compound and its developer dissolve in the solvent will text or an image become visible.

At room temperature, the ink is blue. When heated to 65° Celsius (about 150° Fahrenheit), the solvent melts. That allows the lactone and BPA in the ink to dissolve. When melted, the solvent separates the lactone from the BPA so that the lactone can’t oxidize. This changes the ink from blue to clear.

The ink stays clear once it returns to room temperature. But if you chill the ink to −10° Celsius (14° Fahrenheit) — by putting it in the freezer, for example — the lactone and developer crystallize out of the solution. Now the lactone is able to oxidize again. That restores its sensitivity to heat so that you can again write on the paper.

The words or pictures stay on the paper for at least six months. After that, they may fade. There could be different reasons for that fading. Among them: sunlight, cold temperatures and other chemicals. But under the right conditions, the writing could last longer — maybe even a whole school year.

Long-lasting text and pictures

Chen suspects that other scientists had not thought of this approach because they were looking to come up with a brand-new invention. His group had the idea to instead use something that already existed. These researchers innovated, finding new uses for an existing technology. And that new development can be used for far more than taking notes. For instance, Chen’s group got creative and added its new paper to a phone case. Now the user can print a unique design to customize it.

Qiang Zhao is a chemist in China at Nanjing University of Posts and Telecommunications. A creative mind behind another type of rewritable paper, Zhao thinks that the new one by Chen’s group is neat. Chen’s paper is simple, he notes, and doesn’t cost much to make. For this reason, it should be easy and fairly inexpensive to produce.

However, the paper will need a lot of ink. In large doses, chemicals in the ink, such as that BPA, can be bad for the environment and people’s health. (Studies have shown that BPA can act like a hormone, disrupting how the body functions.) Zhao would like scientists to develop an ink that poses less risk to people and the environment.

Still, he notes, the idea is clever: “This paper will have promising applications in the fields of long-lasting information recording and reading.”

This is one in a series presenting news on technology and innovation, made possible with generous support from the Lemelson Foundation.