People may indeed have a sixth sense — for magnetism

Brain waves hint that humans might possess an ability similar to that seen in some other animals

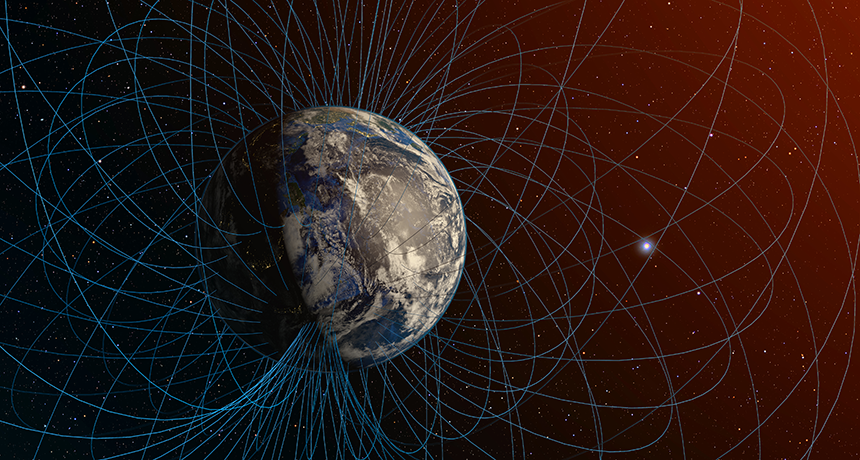

New data suggest that humans may join birds, bacteria and certain other organisms in being able to sense Earth’s magnetic field (illustrated).

vjanez/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Birds, fish and some other creatures can sense Earth’s magnetic field. This ability is known as magnetoreception (mag-NEE-toe-ree-SEP-shun). Many creatures use it navigate. Scientists have long wondered whether humans can do this, too. Now, a study of brain waves suggests people indeed have a “sixth sense” — for magnetism.

In a lab at the California Institute of Technology, in Pasadena, researchers discovered people form a distinct brain-wave pattern when they are exposed to a magnetic field that is equal in strength to Earth’s . But the pattern emerges only when the field points and moves in a certain way. The researchers shared their findings online March 18 in eNeuro.

The discovery offers evidence that people respond to Earth’s magnetic field without knowing it. It’s not yet clear how our brains might use this information.

Biophysicist Can Xie’s first impression of the study was, “Wow, I cannot believe it!” Previous tests of magnetic sense in humans have had mixed results. This new result is “probably a big step for the human magnetic sense,” Xie says. He works at Peking University in Beijing, China.

Catching waves

During the new experiment, 26 people each sat with their eyes closed in a dark, quiet chamber. It was lined with electrical coils. They created a magnetic field that was the same strength as Earth’s natural magnetic field. Researchers could tweak the electric current running through the coils. This would allow them to point the magnetic field in any direction.

Each person wore a cap that recorded their brain’s electrical activity as the magnetic field changed direction. Scientists compared those brain-wave readings with readings from trials where the magnetic field did not move.

The team focused on the brain’s alpha waves. These dominate in the brain as someone sits still and does nothing. But these signals tend to fade as someone uses their senses to smell, taste, hear or touch.

Sure enough, changes in the magnetic field triggered changes in people’s alpha waves. For people in the chamber facing north, the magnetic field pointed down toward the floor. That’s the direction of Earth’s magnetic field in the Northern Hemisphere. Rotating the field left from northeast to northwest made the alpha waves’ height drop by an average of 25 percent. That change was about three times as strong as changes seen in natural alpha wave when the magnetic field had not changed directions.

Curiously, people’s brains showed no response when a rotating magnetic field pointed up toward the ceiling. That’s the direction of Earth’s field in the Southern Hemisphere. This result didn’t change when four people were retested weeks or months later.

“It’s kind of intriguing to think that we have a sense of which we’re not consciously aware,” says Peter Hore. He is a chemist at the University of Oxford in England who has studied birds’ internal compasses. He was not involved in the new research. But Hore notes that the new claim needs more proof. “And in this case,” he adds, “that includes being able to reproduce it in a different lab.”

Science News/YouTube

More questions than answers

If these findings can be confirmed, they pose a few questions. For one: Why do people seem to react to downward- but not upward-pointing fields? The team thinks it has an answer: “The brain is taking [magnetic] data, pulling it out and only using it if it makes sense,” says Joseph Kirschvink. He is a neurobiologist and geophysicist who works at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena.

People in this study all hailed from the Northern Hemisphere. So they should feel downward magnetic fields as natural and upward fields as unnatural, Kirschvink and his colleagues argue. Animals that can sense magnetism can shut off their internal compasses when they come across weird fields that might lead the animals astray. Humans that live in the Northern Hemisphere may similarly take their magnetic sense “offline” when faced with strange, upward fields.

This idea “seems plausible,” Hore says. But it needs to be tested in people from the Southern Hemisphere.

Another question: Why do people’s brains respond to magnetic fields that rotate left but not to the right. It’s something “that we don’t really have a good explanation for,” says coauthor Connie Wang at Caltech.

There may be some people who respond to magnetic fields that rotate right, Wang says. Just like there are some people who are left-handed rather than right-handed. They may exist, just in such small numbers that researchers didn’t have any of them in the new study. Or, magnetic fields that rotate right may affect a different type of brain wave that scientists have not yet looked for.

Even accounting for which magnetic changes the brain picks up, researchers still don’t know what our minds might do with that information, Kirschvink says. How our brains detect Earth’s magnetic field is yet another mystery.

Sensory cells containing a magnetic mineral may explain the brain-wave patterns, say the authors of the new study. This mineral, called magnetite, has been found in trout that sense magnetic fields. It has also turned up in the human brain. Future tests might confirm or rule out that idea.