Defining planethood

Did Pluto deserve to be demoted from the rank of planet in the solar system?

Does Pluto belong among the planets of the solar system? Or is it one of the other types of bodies?

mkarco/ ISTOCKPHOTO

By Emily Sohn

Textbooks are supposed to be full of facts, but you can’t always believe what you read. Especially when the topic is Pluto.

Last August, after 75 years of planethood, Pluto lost its status when the International Astronomical Union (IAU) came up with a new definition of what it means to be a planet.

Within a week, more than 300 scientists had signed a petition rejecting the new definition. An alternative definition would have let Pluto keep its status as a planet and added at least three other objects to the list of planets (see “Pluto and the Plutons”).

No matter what the final verdict, the debate will be a good one, says planetary scientist Mark Sykes. He’s director of the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Ariz.

“It’s an opportunity to lay out what we’ve learned about the solar system in the last 40 years,” Sykes says. “It’s a good diving board to go off into larger issues.”

Out of place

People have known about five planets of the solar system—Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn—since ancient times. Each one is visible to the naked eye. The sixth long-known planet is Earth itself.

|

|

Hubble Space Telescope images of Pluto.

|

| A Stern (SwRI), M. Buie (Lowell Observatory), NASA, ESA |

By 1846, astronomers had found two more planets, Uranus and Neptune, as well as a number of smaller bodies called asteroids. Pluto was discovered in 1930, and scientists labeled it the ninth planet.

But Pluto has always seemed a bit out of place. For one thing, it traces a long, oval-shaped route around the sun, rather than a nearly circular orbit. Sometimes, it gets closer to the sun than Neptune does. Other times, it’s much farther away. And its orbit is sharply tilted compared to the orbits of the other planets.

Pluto’s moon Charon is comparatively large. It’s half the planet’s size. What’s more, the two objects orbit each other. This also sets them apart from other planets and their satellites.

Icy objects

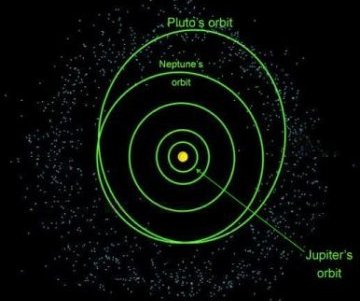

In the early 1990s, astronomers began to suspect that Pluto is part of a newly discovered region of rocky and icy objects called the Kuiper belt. Since then, scientists have found several Kuiper belt objects (KBOs) that are nearly as big as Pluto, including one called Sedna (see “Planets on the Edge”).

|

|

The Kuiper belt, which lies beyond Neptune’s orbit, includes Pluto and other icy objects.

|

| JPL, Caltech, NASA |

The critical point came in 2005, after researchers at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena announced the discovery of a KBO even larger than Pluto. This object, originally called Xena (after a TV character), was later renamed Eris (see “Dwarf Planet Discord”). Its discoverers declared it the “tenth planet.”

“That announcement generated a backlash among some people in the astronomy community,” says planetary scientist Bob Millis, director of the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Ariz. Suddenly, scientists realized that the list of planets could keep growing indefinitely.

In response, the IAU decided to clarify the meaning of the word planet. Until last summer, there had been no official definition.

Official definition

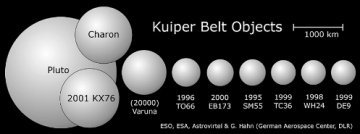

Under one proposed definition, a qualifying object would simply have to orbit the sun and be large enough (and have enough gravity) to be round. Under this definition, Pluto, Charon, Eris, and an asteroid named Ceres would all be considered planets.

|

|

One proposed definition of planet would include not only Pluto but also several other objects, including the asteroid Ceres, Pluto’s moon Charon, and an object now known as Eris.

|

| International Astronomical Union/Martin Kornmesser |

The IAU definition, however, states that a planet must also have “cleared the neighborhood around its orbit.” In other words, no other small objects travel in orbit nearby. Such objects would have disappeared when planets formed early in the solar system’s history. Several weeks after the meeting, the IAU classified Pluto as asteroid 134340.

“[The IAU] came to the conclusion that there is not enough to distinguish Pluto from the overall population of Kuiper belt objects,” Millis says.

In general, those who support the IAU’s decision belong to a group of scientists called dynamicists, Sykes says.

“From that perspective, you think of points of light that move around the sky,” Sykes adds. Dynamicists place less importance on small objects like Pluto, which don’t significantly affect the movements of planets and asteroids, than they do on larger, more massive bodies.

Planetary scientists, on the other hand, are interested in geology and other physical properties. A growing list of planets, in their view, simply adds to the intrigue of space.

“The prospect of there being more planets is daunting for some people,” Sykes says. “For other people, it’s exciting. It’s an opportunity for discovery and knowledge.”

The argument will last at least until 2009, when the IAU meets again.

Destination Kuiper belt

In the meantime, scientists remain deeply interested in Pluto’s neighborhood. Objects in the Kuiper belt may hold secrets about the time when the sun and planets formed. Studying KBOs could also help us learn more about our own planet and planets being discovered in other solar systems.

|

|

The relative sizes of various Kuiper belt objects.

|

| © European Southern Observatory |

So far, surveys have revealed about 1,000 KBOs that are at least 100 miles wide, Millis says. There could be 100,000 more, some as big as or bigger than Pluto.

“This is among the hottest, most vigorously studied subjects in planetary astronomy today,” Millis says. “It is really unplowed territory. There is so much remaining to be discovered.”

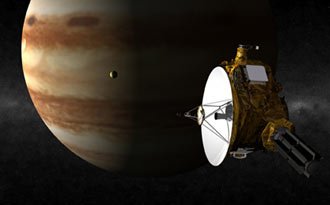

The NASA spacecraft New Horizons is now headed for the Kuiper belt. It took off in January 2006. When it arrives in 2015, it will collect information about the surfaces and atmospheres of Pluto, Charon, and a third KBO. The mission will also search for rings and more moons.

|

|

The New Horizons spacecraft will swing past Jupiter this month, on its way to Pluto and the outer solar system.

|

| NASA |

“Nothing about Pluto has changed,” Millis says. “It is still as significant and important as it ever was.”

As new technologies allow researchers to gaze even farther into outer space, the best strategy for now is to read your textbooks with an open mind.

Definitions, facts, and explanations can change. “Whenever we come up with an explanation for something, we as scientists have to be ready for someone to show us that we’re wrong,” Sykes says.

Each discovery brings new explanations and new ideas.

Comments:

Many of you commented on our previous article about Pluto and the definition of a planet (“Pluto and the Plutons”).

I never would have guessed that the number of planets in the Solar System would change so quickly! Textbooks should be rewritten now!—Deanna, 13

I think that they should just leave Pluto as a planet because now we are going to have to learn about the new planets, and all the people who finished school already don’t have to. We gotta learn about like 1,000 planets and y’all only had to learn about 9. It’s hard enough to memorize 9 planets. Although I do love the name Xena. (p.s. my dog’s name is Xena)—Cassie, 13

Pluto is the best planet.—Sam, 14

I want to consider our moon a planet.—Ethan

I think that Pluto is a planet, because in 5th grade we all learn about planets and Pluto was one of the 9 planets we learned about. I wonder how the scientists can say that it is not a planet after so many years of children learning that it was.—David, 12

I think Pluto should be kept as a planet. It doesn’t feel right without it. I grew up to learn the planets like that. And I think it should be kept like that. So if Pluto remains a planet I’ll be glad. But if not I’ll be sad and confused about why it can’t be kept like that. So I would like to hear what other people have to say about it. That’s just me.—Samantha, 14

I protest! I think Pluto and the others should be part of the solar system! If the scientists are so smart then they can memorize all of them! PLUTO! PLUTO! PLUTO! I say keep Pluto a planet! Come on . . . Think about the public, think about all those people who want Pluto to be a planet! If you don’t make Pluto a planet then I will hate science forever! That’s like killing Pluto and the others!—Jennifer, 10

I think you should leave it and add any others that are like Pluto!! I’m doing a current event on this and it will make for an interesting topic!—Sara, 13

I read this article but I still don’t get the point of demoting Pluto. Once named a planet should always be a planet. But it’s scientists’ choice what to say about the planets. So I’ll just leave it to them.—Amarra, 14

I really don’t think Pluto should be taken out of the solar system just because the scientists made a mistake. We all had to learn about Pluto, so they should just keep it in and learn from their mistake for next time :]—Brittney, 15

Going Deeper: