The trouble with Pluto

Removing Pluto from the planet list is just the latest in an age-old debate on how many planets make up the solar system

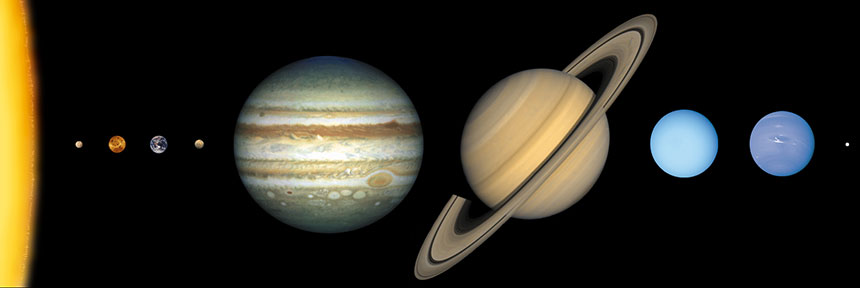

Until recently, the solar system was made up of the sun (far left) and nine planets, including (from left to right) Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune and Pluto -- so small in comparison that it is difficult to make out in this composite image.

Lunar and Planetary Laboratory

Quick — how many planets are there in the solar system? It’s a simple question, but there’s no easy answer. You might have learned there are nine: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune and Pluto. But now that view of the solar system is out of date. Depending on who you talk to today, the answer could be eight, 12, or even 208 and counting.

How is that possible? Over the past 15 years, larger and stronger telescopes have given astronomers a better look at the far reaches of the solar system. Over that time, they have discovered an entire new class of objects orbiting the sun well beyond the orbit of Neptune. Some of these objects are just as big — or bigger — than Pluto. These discoveries have forced scientists to think deeply about what it means to be a planet.

In 2006, the International Astronomical Union defined “planet” in a way that kicked Pluto out of the planet tribe. But many astronomers disagreed with the definition. This summer, they and their colleagues met in Maryland for “The Great Planet Debate.” There, scientists on both sides discussed how to define the new objects being discovered far out in the solar system every year. Some hope the IAU will re-visit the definition of a planet when the organization meets again next year. (Click here to read more about what the scientists discussed at the meeting.)

The questions they’re wrestling with are hardly new. Scientists have been naming, re-naming and categorizing the various parts of the solar system ever since people began looking at and documenting the objects in the night sky thousands of years ago. Over time, new observations and improvements in technology led to a better understanding of the nature of the universe. As a result, scientists have sometimes been forced to re-name objects they thought were planets. Or they have had to define new categories of objects entirely. That’s just what’s happening with Pluto today. And it has been happening for as long as people have been looking toward the night sky.

|

|

This updated illustration of the solar system shows the sun, eight planets and the dwarf planets, which now include Pluto. Other dwarf planets are Ceres and the still unnamed 2003 UB313.

|

| International Astronomical Union |

From seven to 16

It was the ancient Greeks who first coined the name “planet.” The word means “wandering star,” explains David Weintraub. He’s an astronomer at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn. Aristotle, the Greek natural philosopher who lived more than 2,000 years ago, identified seven “planets” in the sky. They’re the objects that today we call the sun, moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. It was a view of planets that held for 1,500 years, Weintraub notes.

“The seven planets according to the Greeks were the seven planets at the time of the Copernicus, and those seven included the sun and the moon,” he says.

Nicolaus Copernicus was the Polish astronomer who suggested that the sun, and not the Earth, was at the center of what we today call the solar system. This was in the early 1500s. He removed the sun from the planet tally. Then, in 1610, Galileo Galilei pointed a telescope to the sky. This Italian mathematician saw, for the first time, the objects we know today as the four moons of Jupiter.

Later that century, the astronomers Christiann Huygens and Jean-Dominique Cassini spotted five additional objects orbiting Saturn. At the end of the 1600s, astronomers agreed that the objects orbiting Jupiter and Saturn, along with those two planets, Mercury, Venus, Earth, Earth’s moon and Mars, should all be called planets. This brought to 16 the number of objects called planets.

Between that time and the early 1900s, the number of objects astronomers called planets fluctuated. It went from a high of 16, back to six when the objects circling planets were reclassified as moons. Then it went up to seven when Uranus was discovered, and up still more, to 13. This was after the initial discovery of several objects lying between Mars and Jupiter — objects we know today as asteroids.

The trouble with Pluto

In 1992, University of Hawaii astronomers David Jewitt and Jane Luu (who is now at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology) discovered a new object in Pluto’s neighborhood, which is beyond the orbit of Neptune. Within one year alone, scientists identified five more objects in the region of the solar system called the Kuiper belt, named for the astronomer who predicted its existence about 60 years ago.

And all these new objects are what got Pluto into trouble, says Guy Consolmagno. He’s an astronomer at the Vatican Observatory and past president of the IAU commission on planets and moons.

|

|

Hubble Space Telescope took this image of the far-away dwarf planet, Pluto (lower left), and its moon, Charon. Pluto was discovered in 1930, but Charon wasn’t detected until 1978. That is because Pluto and its moon are so close to each other that the two tend to blur together when viewed through ground-based telescopes.

|

| R. Albrecht, ESA/ESO Space Telescope European Coordinating Facility, NASA |

“When we first discovered Pluto, it was the only thing out there,” he says.

And so in 2006, the International Astronomical Union passed a rule that changed Pluto from “planet” to a new classification: “dwarf planet.” And just this year, they changed its designation yet again. This time it became part of a new class called “plutoid.”

The new classification considers an object a planet based largely on how it interacts with other objects in the solar system, Consolmagno explains. “The eight major planets are so big they control everything around them,” he says. The larger a space object is, the more powerful is its gravity, the invisible pull that keeps moons circling planets and the planets circling the sun. The gravitational control a planet exerts influences the overall structure of the solar system, Consolmagno says.

“But Pluto is not so big that it defines the gravitational structure of its neighbors,” he says. For that reason, he says, it shouldn’t be considered in the same category as the rest of the planets.

Not all astronomers agree these are the most important traits to consider in planethood. Many others say planets should be classified based on physical characteristics, such as shape, size and geology.

|

|

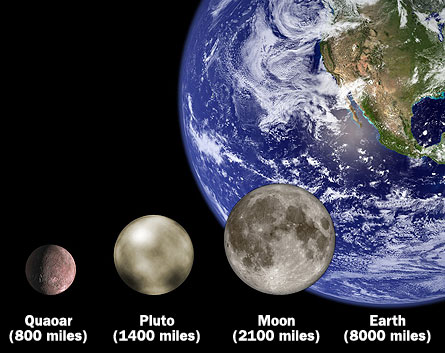

An artist’s illustration shows the size of Pluto in comparison to Earth, the moon and Quaoar, a planetoid in orbit beyond Pluto. The 2002 discovery of Quaoar and other large objects in the Kuiper Belt was part of what led to the decision to change today’s definition of the word planet.

|

| NASA/JPL-Caltech/R. Hurt (SSC-Caltech) |

“It’s not that IAU is wrong, or that I’m wrong — it’s what is the utility of the definition,” says Mark Sykes. He’s the director of the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Ariz. “A lot of my colleagues feel, we really can’t use the system the way the IAU wants to organize it.” He and others prefer to define planets by physical characteristics. To them, a planet is a body that is large enough that its own gravity will crush it into a spherical shape.

Once objects grow this large, he said their interiors become hot enough to produce liquid materials that move below the surface. “At that point, you start getting geology, like the planetary processes [such as volcanoes and plate tectonics] here on Earth,” he says.

Defining planets in this way also opens the possibility that many other objects in the Kuiper belt could be considered planets, Weintraub says. “The likelihood of finding objects there bigger than Pluto are pretty good,” he says. “If you’re not bothered by letting more planets in the room, it doesn’t bother you if there are 16 or 22, you don’t have to come up with a definition that excludes these smaller guys.”

New view of the solar system

In the end, the planet debate exists only because astronomers are trying to make sense of new discoveries about the solar system. As in any field of science, fitting new discoveries into existing categories doesn’t always work. And that’s a good thing, says Alan Stern, planetary scientist and principal investigator of the New Horizons mission to Pluto and the Kuiper belt.

“We’re in the midst of a revolution about the architecture of our solar system,” Stern says. “We used to call Neptune and Uranus the outer planets, but it turns out, they’re in the middle of a much larger system. It’s the outer zone where the action is.”

He compares advances in astronomy today to the age of discovery when Columbus sailed to the Americas in 1492. “Columbus sailed west to get to India and thought he was there. When he found out he wasn’t, the map of the world changed completely. This is a similar kind of revolution,” Stern says.

Consolmagno agrees. “We’re looking at a brand-new class of objects,” he says. “One person told me, as a planet Pluto was always an ugly duckling. But when you look at it as an example of its own category, it’s a beautiful swan. It’s a classic example of a brand-new category.”