Workers won’t work as well in a very warm world

When it gets too hot, workers and businesses lose out

One feature of Earth’s changing climate is warmer temperatures. This extra heat will hurt outdoor workers by reducing how much work they can get done.

Nikada/E+/Getty Images

As climate change continues to warm the planet, more and more of the people who work outdoors will face “hot days.” Think of it as the opposite of snow days. These are periods when excess heat forces local activities to grind to a halt.

Heat can do more than just make it uncomfortable to be outside. A mix of high heat, humidity, low wind and other weather conditions can make it unsafe to do some jobs, such as farming and construction. People’s health can suffer under these conditions. So will family incomes.

Productivity is the term experts use when measuring the quantity and quality of someone’s work. Lost productivity “is a major consequence of the health impacts of global warming,” says Yu Shuang. She’s a climate scientist in Beijing at the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Atmospheric Physics. If heat stress keeps people from working, they won’t be able to earn money. And the impacts of that lost productivity can ripple throughout a country’s economy.

Oliver Andrews is a climate scientist at the University of Bristol in England. Not being able to work, he notes, is especially bad for people who don’t earn much on good days. Having to take even a short climate break from work for excess heat can now rob low-income people of the earnings they need to buy food, to pay for medical care or to cover other costs, he points out. That can tempt people to work in hazardous conditions — even if it ups their risk of illness or death.

In one recent study, Andrews and his colleagues looked at how temperature, humidity, wind and other weather conditions would affect the ability of adults to perform their daily jobs. Those factors combine into a measure of heat stress. It’s known as the wet-bulb globe temperature (WGBT). Anything above a monthly average WBGT of 34° Celsius (93° Fahrenheit) is too hot to work safely for a large part of the month, Andrews says.

On that basis, India, Mexico, Pakistan, Algeria and Chad already face a high risk of work-related heat stress, the team found. But the list would grow as the climate continues to warm. Scientists have been saying many environmental conditions can change dramatically once Earth’s average warming reaches 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) above temperatures typical of a century ago or more. And Earth is closing in on that. Once that temperature threshold is reached, another 15 countries, including Australia, go on the list of places where it often would get too hot to safely work. And the United States and 10 more countries go on after global warming passes 2 °C (3.6 °F) above the old norm.

This study appears in the December 2018 Lancet Planetary Health.

But work productivity can suffer even at lower temperatures. The fall-off can start before the WGBT hits 28 °C (82 °F), notes a report is in the January 2019 issue of Climate Policy.

In many cases, “if workers are less productive, their wages will be lower,” explains economist Sam Fankhauser. He’s one of the report’s authors. He works in England at the London School of Economics. “We know that people’s ability to do certain tasks diminishes when it gets too hot,” he says. “Hard physical work in the heat wears you out quickly. Farmers, construction workers and people in non-air-conditioned factories would need more breaks. This means they would get less work done. And, he adds, when overheated “your cognitive functions are lower.” By cognitive, he refers to our ability to think clearly, perform calculations and make informed decisions.

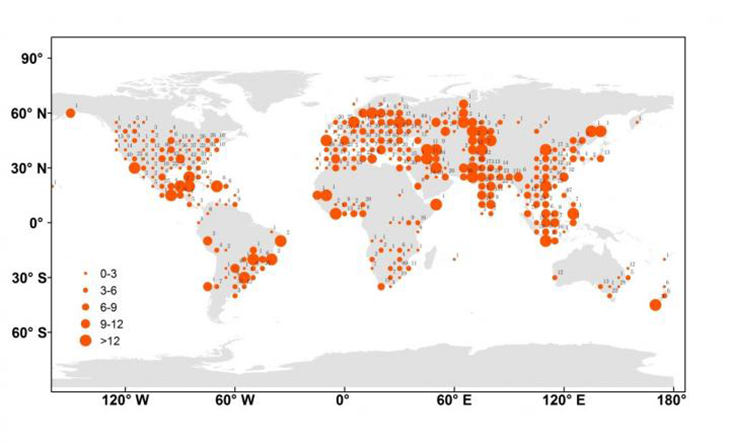

Yu and her colleagues have looked at how many work days different areas would likely lose in a warming world. They found “a worldwide pattern” of loss in worker productivity. And work days lost to heat wouldn’t happen only in tropical and subtropical areas, she reports. Places like northern Europe and Central Asia will feel the heat as well.

Her group’s study appears in the January 20 issue of the Journal of Cleaner Production.

Not all countries will feel these impacts equally. With a 2 °C (3.6 °F) increase in global temps, low-income countries would have about 2.5 times as many lost work days as wealthier nations. At that point, the average worker in a low-income country would lose about 31 days of work each year. At 3 °C (5.4 °F) of warming, they’d lose about 61 days each year. That’s potentially two full months of lost wages.

How to adapt?

Yu’s team hopes its work will guide policy makers to take action. Educating people about global warming and its consequences can help, says Yu’s co-author Yan Zhongwei. He works with Yu at the Institute of Atmospheric Physics. For example, he notes, England has a “heat wave plan.” It outlines ways for people to stay safer and healthier when really hot weather develops.

But such a plan might not work everywhere. Fankhauser and his colleagues have looked at the effectiveness of more than a dozen steps for adapting to heat stress. The best choice for any particular place will depend a lot on local conditions, they conclude. For instance, changes in people’s working hours can avoid them having to work during the hottest part of the day. If people work the same total number of hours, that might be fine. If they wind up working fewer total hours, though, their incomes would suffer.

More air conditioning is another way to beat the heat. That’s fine if the electricity comes from renewable sources and the electric grid is reliable, Fankhauser’s group notes. It’s not so great if the extra electricity would spew more greenhouse gases into the air. That would make climate change worse. It’s also not a good option if the extra use of electricity strains the ability of power plants to supply what’s needed. Failing power plants could result in electrical blackouts, something that tends to happen more in low-income countries.

And, of course, air conditioning doesn’t turn down the heat for outdoor workers. Many developing countries rely heavily on farming or other outdoor work. So again, Fankhauser notes, poor countries would face a disadvantage.