You can fight back against cyberattacks

Cybersecurity experts protect computer systems — and they want your help

“There is no 100-percent-secure software,” says Craig Williams. “It does not exist.” He is one of many cybersecurity experts working to protect people’s data and devices. But everyone should take steps to protect themselves.

PeopleImages/E+/Getty Images

“Grant? How can you hear me?” The voice came through Grant Thompson’s iPhone. The 14-year-old had FaceTimed his friend Nathan to ask if he wanted to play the game Fortnite. But Nathan didn’t answer right away. So Grant swiped to add another friend to a group FaceTime call. All of a sudden, he could hear Nathan and Nathan could hear him. But Nathan had never tapped to answer the call. Both of their phones showed the call still ringing.

This happened on January 19, 2019. Grant, a high school freshman in Arizona, could have shrugged off the strange glitch and spent the evening playing Fortnite. But that’s not what he did. He told Nathan to hang up and called him again. He wanted to see if he could get the call to connect again without Nathan answering. “We tested it for like half an hour,” Grant says. “It worked every single time.”

Feeling shocked and concerned, Grant went to find his mom, Michele Thompson, and tell her what had happened. She decided to test the problem herself. She asked Grant to try to FaceTime her from a different room. When he did, she didn’t answer. Meanwhile, Grant swiped to add his sister to the call. He was too far away to hear his mom’s voice normally. But through his phone, he heard her quietly singing the ABCs.

Grant and his family had discovered a major mistake, also called a bug, in the iPhone’s software. This bug let a person listen to someone else without their permission or knowledge.

Grant’s mom is a lawyer at Udall Law Firm in Tucson, Ariz. She regularly handles privacy issues in her practice, so she knew the bug was a big deal. She reported it to Apple, the maker of the iPhone. “Honestly, I thought it was going to be fixed the next day,” she says. But it wasn’t. For almost two weeks, she tried to get the attention of the right people at Apple.

Meanwhile, others discovered this bug existed. Soon, the cyberbug hit the news and Apple shut down group FaceTime. The bug earned the clever nickname “Face palm.”

On February 7, the company released a software update that fixed the problem. Apple also rewarded Grant. He had been the first person to report the bug. “They gave a gift towards my education,” he says.

The experience taught him to be careful with technology. He also learned that anyone can discover a major security problem. “I stumbled upon this by accident,” he says. “There are probably more glitches like this out there that people haven’t found yet.”

Fighting off black hats

Glitches and bugs can show up in any new piece of software or software update. Lots of people spend their days searching for them. Some of those people are analysts and engineers who focus on cybersecurity. They look for bugs and problems so that they can fix software and protect computer systems. Also on the lookout are cybercriminals, also known as black-hat hackers. They seek bugs that will let them weasel into computer systems, often to wreak havoc.

Christian Science Monitor/YouTube

Cybercrime is a global problem. “The threat is absolutely growing,” says Robert M. Lee. He’s a cybersecurity expert and founder of Dragos, Inc. in Hanover, Md. Some cybercriminals take advantage of bugs to break into a system. If they use a new, unknown bug, it’s called a zero-day attack. Other times they break in using known bugs that some people haven’t bothered to “patch,” or fix. And many cyberattackers simply trick people into handing over passwords or installing harmful software, called malware.

Most cybercriminals target individuals or companies. They may steal money or company secrets. But in rare cases, a cyberattack targets a larger group — say, a whole country. Information and privacy aren’t the only things at risk. Some attacks spread chaos and destruction. If one country directs an attack like this at another nation, that’s an act of cyberwarfare.

Heather King once worked on the National Security Council staff at the White House in Washington, D.C. Part of this group’s job is preparing for cyberwarfare. Now she’s the chief operating officer at a company called Cyber Threat Alliance in Arlington, Va. There, King continues to help protect people from cyberattacks. “Our biggest concerns,” she says, “are attacks on systems we all rely on most.” Attackers may target any system that connects to a computer network. That includes infrastructure, such as the power grid, banking systems, water distribution, satellite networks, air traffic control and more. Attacks like this have already happened.

Blackout

In the middle of the afternoon one late December day in 2015, over 200,000 people lost power in western Ukraine, a nation in Eastern Europe. Almost exactly one year later, a December blackout hit the capital city of Kiev. It plunged part of the city into darkness for more than an hour. These blackouts were no accident. It wasn’t a snowstorm, fire or other disaster that damaged the wires. In both cases, someone had hacked into the system of stations and control systems that bring electricity to homes and businesses, known as the power grid.

Experts believe the same team carried out both attacks. Most likely, this team works for Russia. Russia has been in a conflict with Ukraine since 2014. The two countries disagree about who owns a territory called Crimea (Kry-ME-uh). Both nation’s armies have clashed on the ground, in the air and at sea. At the same time, a battle has raged in cyberspace.

The 2015 cyberattack was the first in the world to take down part of a power grid. Lee responded to the incident as a lead investigator. His job was to figure out how the attack happened.

First, the attackers needed a way into the computer system that controlled the power. So they had sent emails to people who worked at several power companies in Ukraine. These emails had Word documents attached to them. Some employees opened the documents. Then, some clicked to allow the documents to run programs called macros. This secretly installed malware on their computers. The malware gave the attackers a way into the system, also called a back door.

The attackers “fooled the users,” Lee says. In cybersecurity, tricking people into handing over access is called phishing.

For six months, the attackers went undetected as they slipped in and out through the digital back door. They spent this time studying the computer networks that controlled the power grid. They learned the system so well that they could “make it do things it wasn’t designed to do,” notes Lee. Finally, when they were ready, the attackers shut the power down at 67 substations. These are parts of the power grid that divvy out electricity and change its voltage as needed.

In 2016, the attackers upped their game. They targeted and shut down a single, larger substation. Imagine the electrical grid like the network of vessels carrying blood through the human body, Lee says. The 2015 attack hit tiny veins in the fingers. In contrast, the 2016 attack shut down a huge artery.

There was one more important difference between the two blackouts. In 2015, around 20 people were needed to manually type in a series of commands that shut down the power at each substation. By 2016, the group had written malware to automatically mess with the power. It took just one person’s keyboard tap to run it. Lee’s team nicknamed the malware CrashOverride.

By itself, CrashOverride can’t knock out power to an entire country, or even a large city. People still need to hack into each substation in an electrical grid, one by one. And the grids in different countries use different software systems. But the Ukraine attacks “still concern countries,” says Lee. Through their attacks, the hackers learned skills and techniques that would make it easier for them to assault other types of infrastructure.

An ominous ransom note

A cyberattack doesn’t have to directly target infrastructure to spread chaos and disrupt society. In late June 2017, computer systems failed at dozens of companies around the world. One of them was the drug company Merck. Without its computers, Merck could not manufacture medicines. It had to delay delivery of some drugs. Another victim was the shipping company Maersk. It couldn’t get cargo containers onto the right ships or trucks. Crates of perishable food, machine parts and other goods were stranded — in some cases for months.

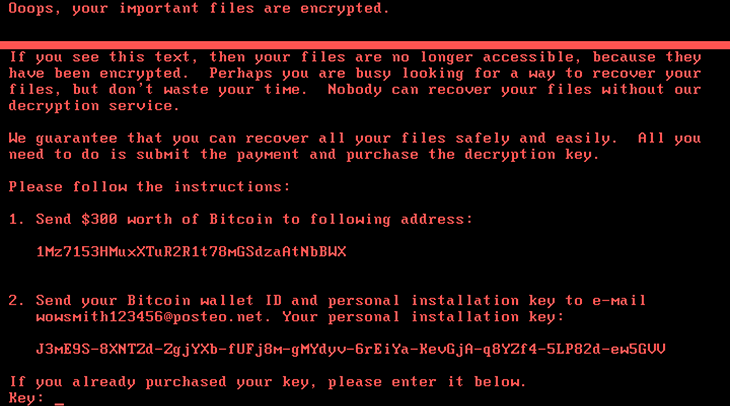

The companies’ infected computers displayed an ominous message. It began, “Ooops, your important files are encrypted.”

It was a ransom note. It meant hackers had locked down that machine. They demanded payment in bitcoin, a type of untraceable online currency. Supposedly, if you paid, you’d get your files back. But that was a lie. “There was no chance to get anything back,” says Craig Williams. The malware had actually wiped the computer clean.

Williams is a cybersecurity expert at Cisco in Austin, Texas. Like King and Lee, his job is to watch out for cyberattacks and respond to threats. He was part of the team that unraveled the story behind the June 2017 attack, nicknamed NotPetya. (Wondering where that weird name comes from? At first, the attack seemed like a variation of Petya, ransomware that emerged in 2016 and got its name from the weapon in a James Bond movie. But experts soon realized this new attack was not Petya at all — it was something much more devastating.)

“It was the worst cyberattack ever,” says Williams. “It was so fast and widespread.” At first, most people assumed it had spread through email. Some companies even shut down their email servers, says Williams. But that wouldn’t have protected them. This time, the attackers had entered another way.

Williams and his team discovered something in common among all the companies that had been infected in the first wave of the attack. They all used the same tax software, called M.E.Doc. This software helped companies file taxes in Ukraine.

But M.E.Doc wasn’t behind the attack. A team of hackers had broken into the company’s computers. Then they had inserted their own code into one of the company’s software updates. All software companies send out regular updates. These updates fix bugs, add new features and usually help to improve security. But in this case, the update opened a back door. Attackers used this back door to launch NotPetya. This malware could spread itself to other computers on the same network, even ones without the tax software.

“People don’t realize how much they depend on computers until they suddenly break,” says Williams. “Life can come to a screeching halt.” That’s exactly what happened for several days that June. Infected companies could not do business. The companies scrambled to rebuild their systems from backup data.

Once again, experts believe Russia was behind the attack. Russian hackers were likely targeting Ukraine, although other countries got caught in the cyber-crossfire. Most of the companies using M.E.Doc software were in Ukraine. The attack took down banks, the postal service, the main airport and many other major companies. All this happened the day before Constitution Day, a Ukraine national holiday. If Russia really is to blame for CrashOverride and NotPetya, then both acts constitute cyberwarfare.

Bad guys vs. good guys

Experts say that we should prepare ourselves for more attacks like these in the future. Lee notes that this year, his team is tracking eight different teams of unknown black-hat hackers that have targeted factories and other industrial systems. They have broken into these systems hundreds of times. So far, these break-ins haven’t led to any disruptions or damage. But the attackers have stolen information, says Lee. They could be waiting for the right time to strike.

The good news is that people like Lee, Williams and King spend their days keeping watch for attacks. “It’s my job to be paranoid,” says King. As the bad guys up their game, the good guys do, too.

“Our ability to counter attacks will continue to increase,” says King. She is confident that in the United States, security officials are doing everything possible to prepare for the next big cyberattack. But everyone has a part to play in making sure technology stays secure — even teens.

“You have to constantly remain vigilant,” says Williams. Teens should never download or install anything unless they know exactly what it is and where it came from. Keeping devices updated also can prevent attacks. For example, the NotPetya attack could spread itself through networks thanks to a known bug in Windows software. Microsoft, the company that makes Windows, had released an update to fix the problem several months before the attack. But many people hadn’t gotten around to installing the patch yet.

Teens should also never ignore their instincts or underestimate their abilities. “I didn’t expect that I was going to find a bug in a huge tech company,” says Grant Thompson. But he did. More importantly, he reported what he had found.

After Grant’s experience, he’s decided that he might want to pursue cybersecurity as a career. He even signed up to take a new IT course that his high school will offer in the fall.

Cyberattacks may seem scary. But they only work when they catch their targets off-guard. You are the defender of your own devices. Governments and cybersecurity experts are working hard to protect infrastructure and other important computer systems.

Williams, for one, loves his job. What could be better than chasing bad guys and solving problems? “Every single day is like playing a giant video game,” he says.