Youthful rebellion leads some teens to eat better

Food choices can improve after students learn how ads have been created to ‘control’ their behaviors

Kids and teens were more likely to choose healthy foods once they understood how food companies have designed ads to manipulate them.

Kiwis/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Do you know that junk food isn’t healthy? Of course you do. Do you eat it anyway? Of course you do! But a new study looks to change that by harnessing youthful rebellion. It shows that teaching adolescents about the ways food companies fool them into thinking junk food is cool can encourage kids to fight back — by eating healthier.

The study’s findings appeared April 15 in Nature Human Behaviour.

The pull of junk foods — ones high in calories and low in nutrients — can be super-strong. They were designed to be tasty. And that makes eating well one of the great health challenges of our time. Everyone from doctors to teachers to the government has been trying to get people to eat well. Yet we keep gobbling junk foods down.

Christopher Bryan is a psychologist at the University of Chicago in Illinois. He knew that simply telling teens to eat fewer junk foods hasn’t driven them to do so. Nor has telling them that eating better today could make them healthier in the future. Most kids aren’t worried about long-term health. (This isn’t just a problem for kids. Adults have trouble acting in their future best interests, too.) “Something that tastes delicious right now is likely to win most of the time,” Bryan says.

But he had a couple of insights. The first was that teens and pre-teens like to make their own choices. They also don’t like it when things are unfair. He decided to try framing healthy foods in a new way by tapping into these two great motivators. Would kids rebel against the corporations that sell junk food by choosing to eat healthy? His team’s new study tested this — and showed that many kids would do just that.

Making junk food addictive

Food companies employ many methods to get people to reach for unhealthy foods. “They want you to want it, whether you’re hungry or not,” Bryan says. These companies spend millions of dollars coming up with new ways to promote junk-food consumption, especially among very young kids. They hire scientists to make new junk foods almost impossible to resist. They might do this, for instance, by adding more sugar. Rats fed junk food for six weeks will even walk across a floor that gives them shocks just to get more of the unhealthy chow.

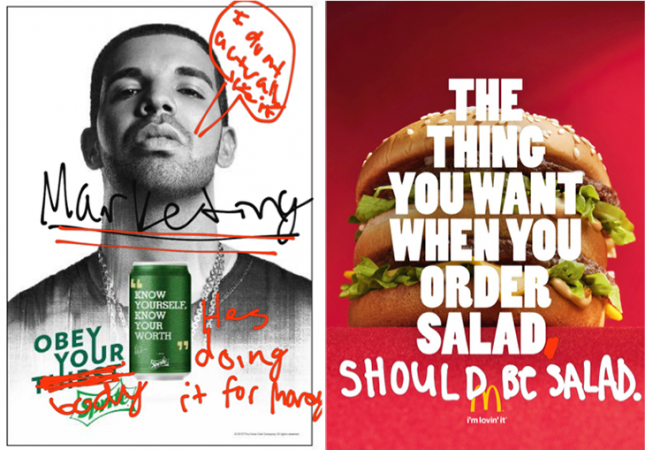

Ads for these foods can be misleading. They often make unhealthy junk food seem healthy by featuring pro athletes, fit-looking pop stars and smiling, active teens. One Gatorade video game for kids, for example, showed Olympic gold medalist Usain Bolt slowing down when he drank water but speeding up when he downed the sugary drink. The tactics used in these ads are similar to the ones tobacco companies have used to try to get people to smoke.

“We thought that when the students learned this, it would matter to them,” Bryan says.

His team worked with 8th graders at a Texas school. Half of the 362 students got a lesson that Bryan created. It focused on the ways junk food is advertised, or marketed. Students in this marketing group read about how effective ads can influence people to eat certain junk-food snacks — even when they’re not hungry. And as part of the lesson, the students were given ads and told: “Make it true.” They were told to put graffiti on the ads to show what the food companies aren’t telling people.

A second group received lessons that focused on health. These lessons informed students that junk food is bad for you, and that foods like apples or carrots are a better choice. A bad diet can lead to major weight gain, the students learned. And the lessons pointed out that being overweight puts people at risk for serious diseases. These students also learned how eating well now can keep you healthy when you’re older.

Healthy choices

After the lessons, the kids in both groups were asked how they felt about junk food. Most didn’t have positive feelings about these unhealthy foods. In the cafeteria, though, the two groups differed in their behaviors.

Overall, girls from both groups bought slightly fewer unhealthy foods. Boys from the two groups differed far more. Cafeteria records showed those in the group given nutrition-based lessons ate as they had been doing before. But boys in the marketing group bought about one-third fewer junk-food snacks, and one-third more healthier foods. And even three months later, this trend had not changed.

Bryan thinks he knows why. Those offered the marketing lessons now framed the idea of healthy eating around things they truly cared about: fairness, truth and making their own choices.

“They don’t want to be controlled by adults,” Bryan says. They also were seeing that when you skip the junk food, you’re fighting back. In this way, healthy food became a form of rebellion.

Michael Pollan is a journalism professor at the University of California, Berkeley. He has written a lot about food issues, and he sees the research as encouraging. “The more kids learn about the tricks companies use to sell them junk food, the less likely they are to eat it,” he says.

“This study offers welcome hope that the right messages can offer some protection,” adds Kelly Brownell. He directs the World Food Policy Center at Duke University in Durham, N.C. “It would also be very helpful,” he believes, if the government regulated food advertising “so that food companies [couldn’t] promote the worst foods in such aggressive ways.”

Robert Lustig is a doctor at the University of California, San Francisco. He studies causes and treatment of childhood obesity. The new study, he says, shows kids can absorb the same lessons he’s learned in years of research. He offered two rules for students: “One: Question everything. Two: Trust the science, not the humans.”