Teens swipe a door handle and find an antibiotic

New types of bacteria are everywhere — and some might make medicines we can use

Atlantis Aziz-Dickerson (left), Joyceline Dweh (center) and D’Asia Buchanan (right) swabbed a door handle, a smartphone and a hand dryer — and found a new bacterium.

A. Sue Weisler

Three high school seniors swabbed a door handle, a smartphone and a hand dryer. They never expected to find anything truly new. But discoveries can turn up anywhere. And these young women helped to find a brand-new bacterium. One day, the microbe might even help produce new antibiotics.

Atlantis Aziz-Dickerson, 18, Joyceline Dweh, 17, and D’Asia Buchanan, 17, are all seniors at Rochester Prep High School in New York. The teens were chosen during the fall of their senior year to participate in a Capstone program. It pairs teens at Rochester Prep with professors at the nearby Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT). Some other Capstone students chose to study photography, computer science or game design. Atlantis, Joyceline and D’Asia chose microbiology, the study of things too small to see with the naked eye.

“I’ve always been interested in science, but I wasn’t sure what type of science I wanted to do,” D’Asia says. “Bacteria sounded like a good thing. And I thought I would get the best experience, because it was hands-on.”

The three teens teamed up with RIT scientist André Hudson. As a biochemist, he studies the chemistry of living things. He and his laboratory members are in to bioprospecting. Prospectors are people who search Earth for valuable substances. They might pan for gold, for example, or search for oil. Bioprospectors search for new organisms that could prove valuable, such as sources of new drugs.

To look for new bacteria, Hudson doesn’t have to go far. People have found only a tiny fraction of the microbial species on Earth. New species are hiding in the soil and on surfaces all around us.

And some of them might aid medicine. Bacteria produce chemicals that can kill other bacteria as they battle each other in tiny turf wars. Scientists have turned those chemicals into antibiotic medicines to fight our own infections. So far, those medicines have served people well. But now there is a need for new weapons. That’s why Hudson’s lab goes bioprospecting. “We have to look at all the possibilities,” he says. After all, many of the antibiotics that doctors use today originally came from soil bacteria.

When Atlantis, Joyceline and D’Asia started in Hudson’s lab, they thought they would be sampling soil. Instead, Hudson asked them to sample things that people touch every day. So D’Asia swabbed her smartphone. Joyceline sampled the hand dryer in the bathroom. Atlantis swabbed the door handle to the largest science classroom on the RIT campus.

Going on a bug hunt

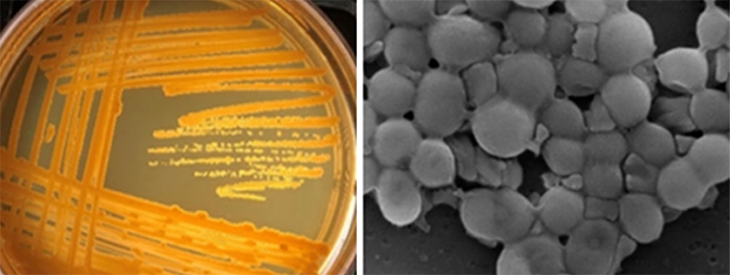

Working with Hudson and others, the three teens grew the bacteria from their swabs in dishes in the lab. One species from the door handle stood out. It formed bright yellow colonies. The girls then sequenced its DNA: They studied the order of its nucleotides — chemical building blocks that made up DNA’s code. That code revealed that this germ belongs to the genus Yimella and probably was a new type, or strain. The bacterium now has a name: Yimella sp. strain RIT 621 (RIT for the school where it was found).

“I was surprised,” Joyceline says. “When I first started doing the project, I didn’t think anything would come out of it.” But she and the others had found a new germ living on an ordinary door handle at RIT. Together with Hudson and other members of his lab, these teens published their findings April 25 in Microbiology Resource Announcements.

This new Yimella also turned out to have a useful talent. Atlantis, Joyceline and D’Asia extracted chemicals the bacterium made. They found the bacterium produced something that could kill two other types of bacteria. Their Yimella could kill a strain of Escherichia coli (or E. coli). The other was a strain of Bacillus subtilis.

“I was scared at first because I thought it could be another superbug” — some microbe that resists antibiotics, Atlantis says. “Then when I learned it killed E. coli, I was excited because it’s doing some good.”

Yimella’s germ-killing trait might lead to a new antibiotic. But that would be true only if Yimella’s antimicrobial chemical was one that scientists hadn’t seen before.

“It’s a start,” says Brittany Bennett. She is a microbiologist at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. “There’s still a lot of work that needs to be done” to identify the antimicrobial compounds and see whether they’re new. “It’s a long process,” she notes. But the new finding does show promise, she says. “These students have shown you can go just about anywhere and find something new.”

It’s essential to keep looking, adds Blanca Barquera. She’s a microbiologist at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, N.Y. “It’s pretty impressive what these students did,” she says. In fighting germs, she explains, “Anything we can do now is helpful. The bacteria are winning, and we are not doing very much [about it].”

Atlantis and Joyceline both want to continue studying science in college. D’Asia has decided to pursue her interest in math. And Hudson has already signed up to have more high school students join his lab to help out in his bioprospecting. “I love it,” he says. “When I was a wide-eyed kid and intimidated, I [worked] in someone’s lab… That’s what made me a scientist today. I’m paying it forward.”