Slow hurricanes, like Dorian, become dangerous and hard to predict

Monster storms that stall, as Dorian did, pose special threats

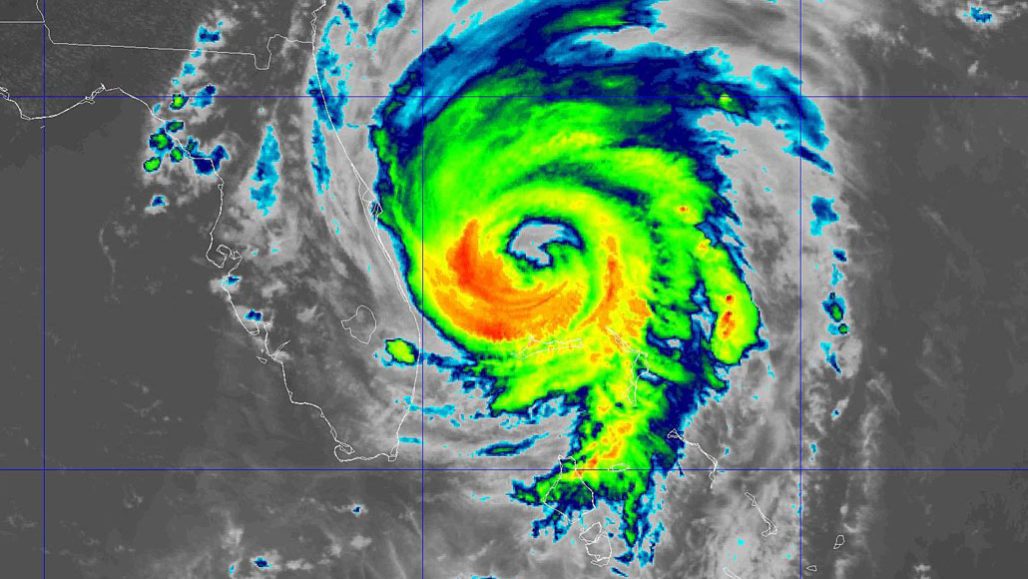

Hurricane Dorian shown on September 3 as it was leaving the Bahamas as a category 2 storm. It was a powerful category 5 when it first slammed into the island nation September 1.

NOAA/NESDIS/STAR

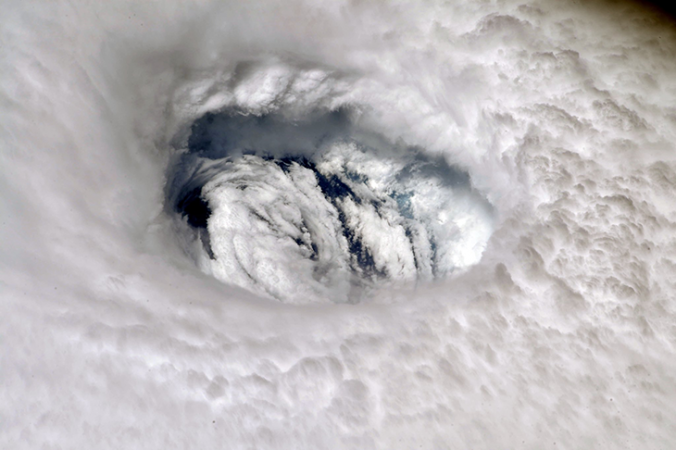

Hurricane Dorian has been a slow, rough beast of a storm. Starting as a category 5 monster as it blew into the northern Bahamas, it stalled there for more than 24 hours. All the while, this near record-breaking cyclone pummeled the islands with wind, rain and surging seas. When Dorian finally got moving again on September 3, it slouched northward toward the U.S. coast as a category 2 hurricane. At that point, it still had sustained winds of about 177 kilometers per hour (110 miles per hour).

The second-strongest Atlantic hurricane on record — and strongest outside the tropics — Dorian made landfall in the Bahamas on September 1. East of southern Florida, this nation consists of some 700 islands and more than 2,000 coral reefs (known as cays). At landfall, Dorian blew with sustained winds of about 298 kilometers per hour (185 miles per hour). Its fury was dangerous. But exaggerating its impact was the fact that this storm stalled over the northern Bahamas for more than a day. It shifted a mere 40 kilometers (around 25 miles). That’s the second slowest trek for an Atlantic hurricane (after 1965’s Betsy, a cat 4 hurricane). Dorian’s snail’s pace challenged forecasters as they tried to predict the storm’s likely trek west toward the United States.

Dorian is just the latest of several recent strong but sluggish cyclones. The trend included 2017’s Hurricane Harvey, 2018’s Hurricane Florence and Cyclone Idai, which struck Mozambique in March. In fact, over the past 70 years, cyclones around the globe have been slowing down, notes James Kossin. He’s a climate scientist based in Madison, Wisc., who works for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Stalled cyclones mean more extreme rainfall. And that poses a major threat to coastal communities in a storm’s path. That was true for both Harvey and Florence, according to Kossin and climate scientist Timothy Hall of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York City. They had a paper on such storms in the June issue of Climate and Atmospheric Science.

Some parts of the Bahamas saw more than 61 centimeters (2 feet) of rain from Dorian, according to NASA’s satellite-based estimates. They were released September 3.

Hall talked to Science News about Dorian’s stall and what scientists can say about its link to climate change.

SN: What does it mean for a storm to stall?

Hall: “Hurricanes are like corks floating on a stream,” he says. “Their paths are determined by the large-scale wind fields in which they sit. When those wind fields collapse temporarily — like they did for Dorian and did for Harvey in 2017 — the hurricane doesn’t have any guidance. It just stalls until a new set of wind fields is in place.”

The National Hurricane Center posts storm characteristics every six hours. In his and Kossin’s June paper, he notes, “We defined meandering as an abrupt change in direction from one six-hour time step to the next. If the center of the storm spends at least 48 hours within a 200-kilometer [124-mile] radius, we called it a stall. We just did an unofficial analysis of Dorian and it was clearly a stall.”

In fact, he says of Dorian over the Bahamas, “It basically came to a complete standstill.”

SN: Is there a link between stalling and climate change?

Hall: From what climate scientists know about climate change and hurricanes, “Some things are virtually certain. Rising sea levels are leading to more coastal flooding, for sure. And increased rainfall is a pretty robust projection from changing climate. There’s a strong consensus now in the [climate-science] community that the intensity of tropical cyclones is getting stronger.”

Other things are less well-known, but still important. Among them, he says, is how climate change might affect a hurricane’s path — “which would include the propensity to stall.” In a warmer climate, he notes, “the large-scale wind patterns in the atmosphere may slow down.”

Currently, he says, it’s still hard to tease out that signal from direct observations. “It’s really at the edge of what we understand.”

SN: You found that stalling hurricanes mean more heavy rains.

Hall: Harvey certainly stalled, he says. But aside from that, he notes that “there was so much rainfall that was driven by waters in the Gulf of Mexico that were extremely warm. Something like between 10 and 25 percent of the rain that fell on Houston could be attributed to human-induced warming.”

As for Dorian, “the waters were very warm in the region where it stalled as well.” They are a couple of degrees Celsius above the average for this time of year. But the gold standard for linking weather events to climate change are what’s known as attribution science studies. And it’s too soon to have one of those for Dorian.

SN: What’s the takeaway for now?

Hall: “I’m glad that people are talking about stalling as an additional feature in the hazards of tropical cyclones. It just highlights how, yes, category [storm intensity] is important. But it’s not the be-all, end-all of a storm’s hazard. There’s the physical size of the storm, how it moves, the angle at which it impacts the coastline — all of which are going to have an effect on storm surge and flooding.