Meat-eating pitcher plants feast on baby salamanders

Once trapped in the plants, the young amphibians can take more than two weeks to die

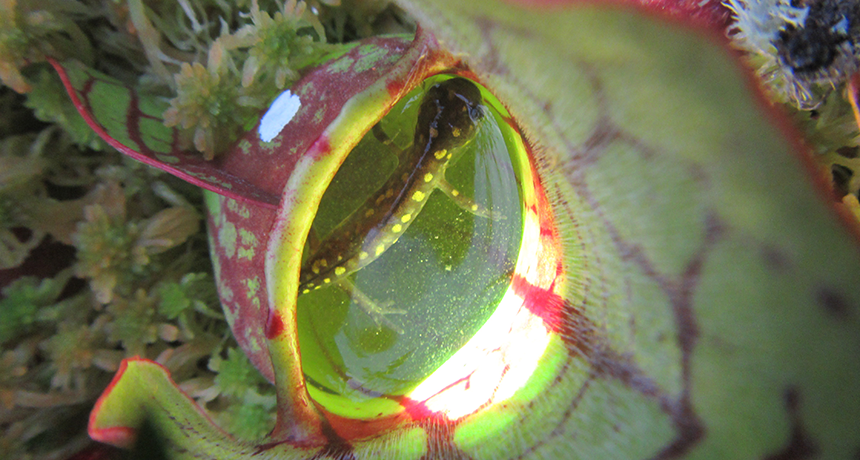

Once trapped, baby salamanders rarely escape the northern pitcher plant. The inside of the plant’s leaves has a slippery coating that makes it hard for the amphibians to climb out.

Patrick D. Moldowan

Carnivorous plants in Ontario’s Algonquin Park don’t eat just bugs. These Canadian pitcher plants also snack on young salamanders.

Until now, scientists hadn’t thought that meat-eating plants in North America ate vertebrates. Those are animals with a brain, two eyes and a backbone. Vertebrates includes amphibians, reptiles, birds, mammals and fish.

Pitcher plants in Asia do eat vertebrates. Some make a meal of small birds and mice. But those in Canada and the United States feed mostly on insects and spiders. Those creatures fall into the plant’s bell-shaped leaves and then gradually decompose in the small pools of rainwater that these plants collect.

Scientists had recorded seeing the odd baby salamander trapped in a northern pitcher plant. Until now, however, no one had looked carefully enough to realize these plants might regularly dine on them. That’s probably because most biologists study pitcher plants in the spring and early summer, before it starts to get too cold, says Patrick Moldowan. He’s a graduate student at the University of Toronto in Canada.

He headed a team that went into the field to study these plants in late summer and early fall. It’s when young yellow spotted salamanders end their larval stage. They now begin crawling out of ponds and onto land.

One in every five pitcher plants in a small pond near the Algonquin Park Wildlife Research Centre contained a young salamander. Each was about two to three centimeters (0.8 to 1.2 inches) long. Moldowan and his team described their findings on June 5 in the journal Ecology.

Caught while stalking lunch?

The pitcher plants here grow some 8 to 10 centimeters (about 3 to 4 inches) tall. Moldowan and his team think the salamanders may climb up the plant in search of tasty insects. If they’re not careful, young amphibians may slip on the waxy leaves. Few that fall into the pitcher’s collected rainwater make it out, he says. The insides of the leaves are just too slick.

“The first time I saw a trapped salamander, my heart went out to it,” recalls Moldowan. “It looked like it was struggling.” He thought about rescuing the salamander. Then he changed his mind. “It got caught fair and square,” he says. In ecology, it’s often eat or be eaten. And these guys were about to become lunch — and dinner and breakfast — for quite a while.

Moldowan and his team found trapped salamanders took anywhere from three to 19 days to die. They are not certain how the salamanders die, but they may starve or succumb to exhaustion as they struggle to escape. Or they might get eaten alive, Moldowan says. Pitcher plants produce enzymes. These are molecules made by living things to speed up chemical reactions. Some enzymes help plants break down a meal into digestible components.

“Another theory is equally grisly,” Moldowan admits. The young salamanders “may essentially get cooked.” There is very little water inside the plant, so “standing in the sun, it will heat up.”

A rotten discovery

In the summer of 2017, Teskey Baldwin, a student at Canada’s University of Guelph, was studying whether pitcher plants near water capture more insects than those farther away. During his fieldwork, Baldwin spotted a salamander rotting in a pitcher plant. He scooped it into a jar.

That evening, over dinner at the Algonquin Wildlife Research Station, he showed the jar to Moldowan.

Algonquin Wildlife Research Station/YouTube

“It was hard to tell what it was because it was pretty decomposed,” Moldowan recalls. But then Baldwin found other salamanders in pitcher plants, and these were immediately recognizable.

Last year, Moldowan decided to take a closer look. That’s when he saw how many of the amphibians were losing their lives this way. He now thinks salamanders may be an important source of nitrogen for the plants. Nitrogen is an essential nutrient for all living things. But the bogs and ponds where pitcher plants grow have very little of this nutrient.

“When they catch salamanders, it’s close to the end of the growing season,” says Moldowan. “Our hunch is that the plants bank the nutrient pulse for the next year. It’s like nutritional money in the bank.”

Unanswered questions abound

Like any piece of science, this study leads to new questions, says Stephen Heard. A biologist, he studies plant-insect interactions in eastern Canada at the University of New Brunswick in Fredericton.

“I wonder how much nutrition the plants are actually getting from the captured salamanders,” he says. “Does a plant that’s lucky enough to catch a salamander grow more quickly or make more seeds than a less lucky plant?”

Heard also wonders about the salamanders. Are enough getting caught in pitcher plants to drive the salamander population down?

These are all good questions, says Moldowan. And he hopes to answer them over the next few years. “It’s not a lion chasing down a gazelle on the Serengeti,” he says. Still, he notes, salamander-eating plants is “a pretty cool predator-prey interaction.”