artifact Some human-made object (such as a pot or brick) that can be used as one gauge of a community’s culture or history. (in statistics or experiments) Something measured or observed that is not naturally a part of some system. It was instead introduced accidentally as a result of how the measurement or study was performed.

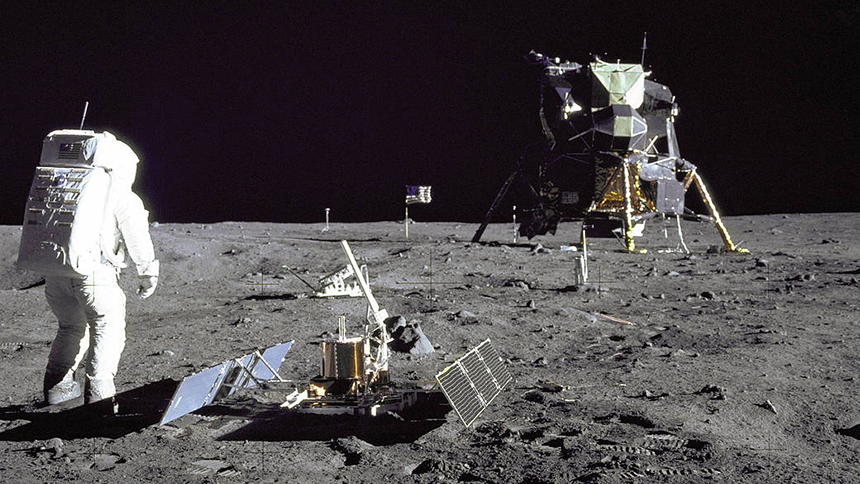

astronaut Someone trained to travel into space for research and exploration.

culture (n. in social science) The sum total of typical behaviors and social practices of a related group of people (such as a tribe or nation). Their culture includes their beliefs, values and the symbols that they accept and/or use. Culture is passed on from generation to generation through learning. Scientists once thought culture to be exclusive to humans. Now they recognize some other animals show signs of culture as well, including dolphins and primates.

debris Scattered fragments, typically of trash or of something that has been destroyed. Space debris, for instance, includes the wreckage of defunct satellites and spacecraft.

engineering The field of research that uses math and science to solve practical problems.

exhaust (in engineering) The gases and fine particles emitted — often at high speed and/or pressure — by combustion (burning) or by the heating of air. Exhaust gases are usually a form of waste.

lunar Of or relating to Earth’s moon.

milestone An important step on the road to stated goal or achievement. The term gets its name from the stone markers that communities used to erect along the side of the road to inform travelers how far they still had to go (in miles) before reaching a town.

moon The natural satellite of any planet.

NASA Short for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Created in 1958, this U.S. agency has become a leader in space research and in stimulating public interest in space exploration. It was through NASA that the United States sent people into orbit and ultimately to the moon. It also has sent research craft to study planets and other celestial objects in our solar system.

relic Something that is a leftover from an earlier time. The term is usually applied to things that had been fashioned by people.

remnant Something that is leftover — from another piece of something, from another time or even some features from an earlier species.

rocket Something propelled into the air or through space, sometimes as a weapon of war. A rocket usually is lofted by the release of exhaust gases as some fuel burns. (v.) Something that flings into space at high speed as if fueled by combustion.

subtle Some feature that may be important, but can be hard to see or describe. For instance, the first cellular changes that signal the start of a cancer may be visible but subtle — small and hard to distinguish from nearby healthy tissues.

treaty A formal agreement that two or more sovereign powers (usually countries or tribal nations) have adopted, giving its provisions the force of law.

vacuum Space with little or no matter in it. Laboratories or manufacturing plants may use vacuum equipment to pump out air, creating an area known as a vacuum chamber.

waste Any materials that are left over from biological or other systems that have no value, so they can be disposed of as trash or recycled for some new use.