Air pollution intensifies a teen’s feeling of stress

Those who are anxious or depressed feel the biggest effects

Teens who are depressed are more likely to become stressed out as a result of breathing polluted air.

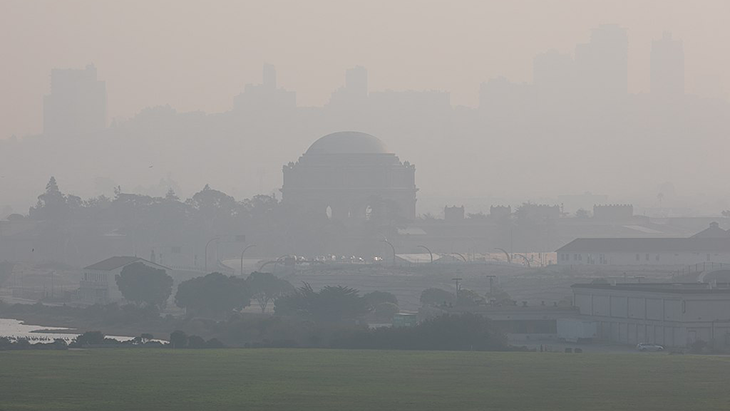

joegolby/iStock/Getty Images Plus

Adolescence is a stressful time. From friends to school to families, stressful situations become common. The body can respond with faster breathing, a pounding heart, tense muscles and beads of sweat. And teens who breathe polluted air appear to respond most strongly to stress, a new study shows. Those with anxiety or depression appear especially sensitive to these pollutant effects.

Air pollution harms health in many ways. People who regularly breathe dirty air are more likely to have immune disorders, heart disease or lung cancer. And the smaller the pollutant particles, the bigger the problem.

Particles less than 2.5 micrometers (0.0001 inch) across seem to wreak the most havoc. These tiny pollutants come from car engines, coal-burning power plants and fireplaces. It would take about 30 of these micro-pollutants to span a human hair. Because they’re so small, they’re easy to breathe in. They irritate the lungs and make people cough. But they don’t stop there. They cross into the bloodstream and reach the brain. And wherever they end up, they can trigger inflammation and other types of harm.

Some studies suggest that air pollution is also linked to mental health problems. However, it hasn’t been clear whether air pollution causes those issues.

Stressing out

Jonas Miller wanted to know whether or how air pollution might affect the body’s response to stress. A psychologist, Miller works at Stanford University in Palo Alto, Calif. He was especially interested in stress in teens. Miller knew adolescence can be full of social challenges. And most tweens and teens spend more time outdoors than do adults, so they can breathe in more of those tiny pollutants.

Miller’s team recruited 144 tweens and teens for their study. Most of the kids lived in or near San Francisco, Calif. It ranks among the 10 U.S. cities having the worst air quality. San Francisco also collects data on air pollution throughout the city. Miller used those data to see how polluted the air was near each recruit’s home.

Miller’s team collected physical and social information about the students. They also recorded each recruit’s height and weight and whether they had started puberty. The students also reported where they lived and how much money their parents made. The participants then answered questions about how they felt. For instance, they might answer whether they were anxious or felt liked by others. Each student also visited the lab at Stanford to participate in a stressful test.

Before the test, a researcher hooked each participant up to a heart rate monitor. They put sensors on one hand to measure how much a student sweated. The sensors recorded heart rate and sweat levels for five minutes as the participant rested. Then the test began.

A member of the research team read aloud the beginning of a story. The researcher then told each recruit that they had five minutes to make up an exciting ending to the story. They would have to memorize their ending and present it aloud to a judge.

After finishing this task, the judge had the participant do math problems. If he or she made a mistake, the judge had the student start over. The whole time, sensors recorded heart rate and sweat levels.

At rest, all the students had similar heart rates and sweat levels, Miller found. That was true no matter where they lived or how dirty the air was near their home. But as the test got tough, differences began to emerge. Kids from neighborhoods with more air pollution reacted more strongly to stress. Their heartbeats became irregular. They sweated more than teens who lived in cleaner places. And these effects were twice as strong for students who reported anxiety or depression.

Threats from the air

Anxiety causes fight-or-flight responses. Miller looked at other possible causes of those strong reactions in the students. He considered body mass and stage of puberty. He looked at family income and neighborhood. And he noted whether the participant belonged to a minority racial or ethnic group.

Only air pollution explained the stronger stress response in anxious or depressed teens.

The teens’ “bodies were preparing to deal with possible threats or challenges in the environment,” Miller concludes. Such bodily responses to stress are linked to negative feelings, he notes. Over time, he says, these responses can “contribute to problems with both physical and mental health.”

His team published its findings September 1 in Psychosomatic Medicine.

“This is an interesting study,” says Anjum Hajat, who was not involved with the project. She works at the University of Washington in Seattle. As an epidemiologist, she studies the causes of disease. Miller’s study “provides unique evidence of the negative health impacts of air pollution among adolescents,” she says.

Hajat points out that the study used data on fine (very small) particulates collected at the neighborhood level. “Many existing air-pollution models can accurately predict [such air pollution] at an individual’s residence,” she notes. Future studies may provide a more accurate picture of how much air pollution a given person really breathes.

How can teens limit their exposure to air pollution? They “should consider limiting their time outside during rush hour,” Miller says. That’s especially important “on days when air pollution is particularly strong.” Indoors, he notes, using air purifiers with HEPA filters can help reduce exposure to tiny pollutants.

Teens also should get mental help when they need it, Miller says. “Treating symptoms of anxiety and depression can boost people’s resistance to the harmful effects of fine-particle air pollution,” he suspects.