Spotted: An exoplanet where it might rain

Two teams have detected signs that the world, called K2 18b, has a damp atmosphere

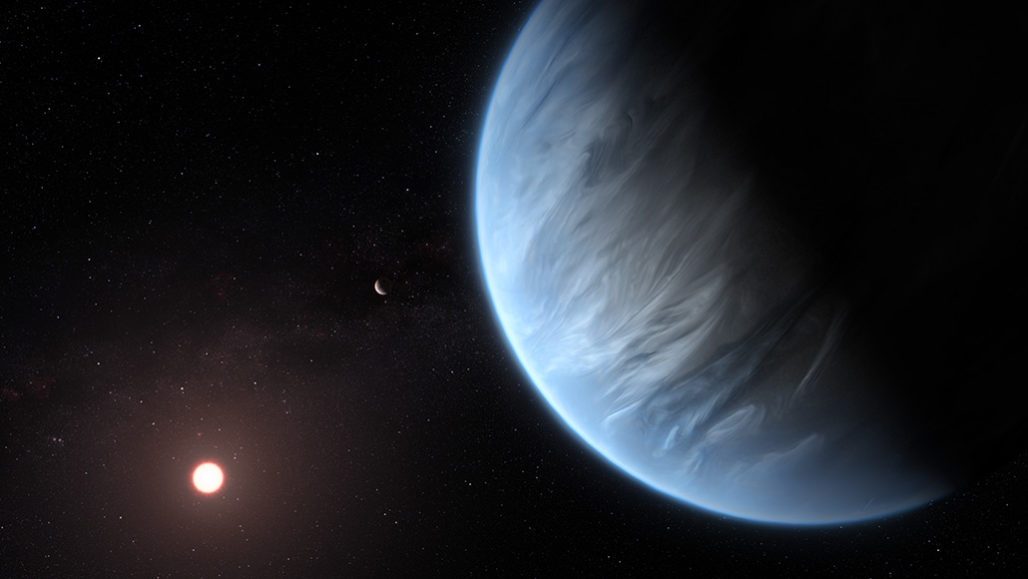

Exoplanet K2 18b, shown in the foreground of this artist’s depiction, might have liquid water. It has clouds and could rain, too.

M. Kornmesser, Hubble/ESA

There might be rain in the forecast for at least one distant planet.

Far outside our solar system, it’s called K2 18b. Data from space telescopes and computer models suggest that this planet’s atmosphere hosts water vapor. If true, it could be the first exoplanet that has liquid water — an essential ingredient for life as we know it.

“Water vapor exists everywhere in the universe,” says Björn Benneke. He is an astronomer in Canada at the University of Montreal. On September 10, his team reported the potential discovery of water on K2 18b at arXiv.org. “It’s not so easy to make liquid water,” Benneke notes. “You need the right pressure and the right temperature,” he points out. “That’s what makes this planet special.”

Astronomers first spotted K2 18b in 2015. They were using the Kepler exoplanet-hunting space telescope. Kepler revealed that the planet orbits a dim star known as a red dwarf. The star and planet are some 110 light-years from Earth. The planet is bit more than twice as wide as Earth, and has eight times Earth’s mass.

So it’s “not an Earthlike planet,” Angelos Tsiaras explained in a September 10 news conference. He is an astronomer in England at University College London. His team also studies K2 18b. And they, too, have detected water vapor in K2 18’s atmosphere. Tsiaras’ team reported that September 11 in Nature Astronomy.

Though not Earthlike, the planet sits in what astronomers call a habitable zone. This is a region around a star where planets could have just the right temperatures to host liquid water. And liquid water appears important for life.

Could this planet host life?

In 2016 and 2017, Benneke’s group studied K2 18b using the Hubble Space Telescope. They wanted to see if the planet had an atmosphere. So they studied the planet as it passed in front of its star. The astronomers were looking to see if the planet’s atmosphere absorbs some of its star’s light. Astronomers can tell which molecules are in a planet’s atmosphere based on which wavelengths of starlight they absorb.

Tsiaras and his team accessed the data Benneke‘s team had collected from a public archive. Then it used specially designed computer software to analyze those data. This revealed the planet indeed had an atmosphere. And the wavelengths of light it absorbed were a signature for water vapor. That meant the planet’s atmosphere held water. That atmosphere also contains hydrogen and helium, the team reports.

“Until now, the planets for which we had the atmosphere observed and found water were gas giants,” Tsiaras says. Those are planets “similar to Jupiter, Saturn or Neptune. Its size, watery atmosphere and location in its star’s habitable zone, make this planet unique, he says. In fact, he adds: “This is the best candidate for habitability that we now have.”

Rain may fall — but how far?

Benneke’s group took the work a step further. They observed the planet with the Spitzer space telescope. By combining observations from Hubble, Spitzer and Kepler, they now believe the planet’s atmosphere has clouds. They appear to form at a specific spot. Knowing where this is, Benneke and his team simulated the planet’s climate. And that spot where the clouds form, they now say, could have the right pressure and temperature for liquid water to form and condense out as rain.

“It’s quite likely that this planet has liquid rain on it,” Benneke concludes. “This is actually one of the most exciting findings from this data.”

However, he adds, those raindrops might never hit solid ground. Instead, they could reach a point in the planet’s thick atmosphere where the pressure and temperature are so great that the droplets just evaporate. That water vapor would then rise back up again to form clouds. That would suggest “there’s a bit of a water cycle,” Benneke says.

Other exoplanet experts aren’t so sure. “There is no definitive proof” of raindrops, says Sara Seager. She is an astronomer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. The idea of rain is “solid, but still speculative,” she believes.

She also points to another caveat. K2 18b may have liquid water, but that doesn’t mean anything lives — or can live — on this planet. One reason: K2 18b might not have solid ground. It’s not clear if the planet has a rocky surface. And that’s where life as we know would be expected to evolve. Most exoplanets in the Milky Way galaxy fall in the size range of this planet, she notes. But it’s hard to tell if those planets are rocky super-Earths, gassy mini-Neptunes or sodden water worlds.

From what astronomers can tell, this is “one of these really mysterious planets that are the most common type of planet in our galaxy,” says Seager. “We have no idea what they are.” Future observations with NASA’s planned James Webb Space Telescope may help. Those observations might be able to pin down how much water K2 18b contains. And that, Seager says, could help astronomers come to understand its composition.