Carnivorous plants say ‘cheese’

It took high-speed cameras to reveal how the bladderwort gets lunch

If you were hiking and came across a plant called a bladderwort, you might stop to admire its small, yellow flowers floating on a puddle. And then walk on. But if you were smaller than a flea and lived in the water, you wouldn’t admire the plant ― you’d probably become its dinner.

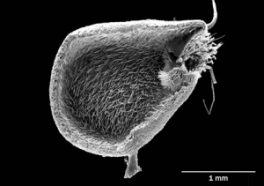

That’s because the bladderwort is one of the fastest bug-eating plants on the planet. Under the water, the plant’s stems hold tiny bags, or bladders, that look like tilted teardrops. When an unsuspecting bug gets too close, the bag opens and — whoosh! — pulls the bug inside.

Using high-speed cameras, French and German scientists recently recorded videos of these plants in action, providing a closer look at how bladderworts trap their prey. Each bladder has an opening at one end, sealed with a tiny covering and with sensitive hairs near the opening. When a bug swims near this mouth and brushes a hair, the door flies open. Water rushes in, bringing in the bug.

The whole process happens in less than a millisecond, which makes bladderworts some of the fastest plants on Earth, say the scientists. There are 1,000 milliseconds in one second. A millisecond passes quickly. In one millisecond, a car going 60 miles per hour travels barely one inch. There are more than 300 milliseconds in the time it takes to blink an eye.

Scientists, including the famous naturalist Charles Darwin, have marveled at the bladderwort’s traps for more than 100 years. However, the action is too fast to see with the human eye, and researchers weren’t sure how the traps worked. Superfast cameras have now revealed what the human eye or even traditional cameras could not see.

Before a bug comes along, the plant pumps out all the water that came in with its last meal. The walls gently curve inward, making the bag resemble a deflated balloon. The door at the end of the bladder is flexible and has small hairs that stick out into the water. The seal is tight, and neither air nor water can get in or out. The trap is ready.

Bladderworts eat small bugs, such as one-eyed Cyclops, tiny crustaceans that live in the water. (Crustaceans have segmented bodies and hard shells; larger crustaceans include shrimp and lobsters.) When one of these delicious bugs triggers a bladderwort’s hair, everything changes in a flash, including the shape of the bladder. The door bursts open and the trap’s walls relax. Water rushes in and fills the trap so fast that the bug doesn’t have time to escape before the door shuts again.

“This kind of change of shape is very abrupt,” Philippe Marmottant told Science News. Marmottant is a physicist at Joseph Fourier University in Grenoble, France, and worked on the study.

In 2005, physicists predicted how the trap works. The new study and its bladderwort movies give them a chance to see the trap in action, and to see that the prediction was correct, Victor Albert told Science News. Albert, a biologist at the University at Buffalo in New York, did not work on the study.

Next time you see a bladderwort’s blooms ― which usually show up in spring or summer, and can be observed almost anywhere in the world — be thankful you’re not a Cyclops swimming nearby.

POWER WORDS (adapted from the Yahoo! Kids Dictionary)

carnivorous plant A plant that can trap insects or other small organisms for food.

bladderwort A carnivorous plant that lives in the water or wet soil. Bladderworts have small, urn-shaped bladders that trap insects and crustaceans.

crustacean An animal that usually lives in the water and has a segmented body and hard exoskeleton. Crustaceans include lobsters, crabs, shrimps and barnacles, as well as many smaller species.

millisecond One-thousandth of a second.