Color-changing bugs

A species of South American beetle changes color from shiny gold to dull red—and back again.

By Emily Sohn

A variety of animals can dramatically change the colors of their bodies to blend with the environment or to ward off predators, among other reasons.

Such creatures, including chameleons and squid, usually switch shades by altering the size of special cells. These cells carry colored chemicals called pigments.

The Panamanian golden tortoise beetle also changes colors—from gold to red. Instead of using pigment cells, however, the bug uses an entirely different strategy to make the color switch.

|

|

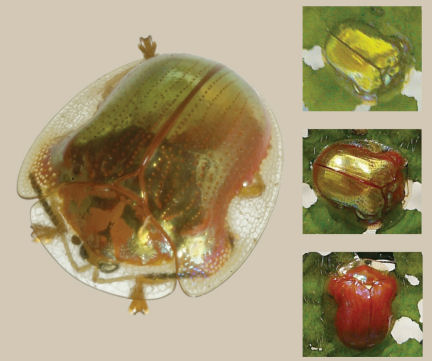

Pictured at the left is a golden tortoise beetle. The images at the right, from top to bottom, show how the beetle uses its shell structure to turn from gold to red.

|

| M. Guerra |

The color-changing beetle, called Charidotella egregia, grows to be about 8 millimeters (0.3 inch) long. It has a see-through shell. Usually, the shell reflects a metallic-gold color. But when the insect is disturbed, the gold hue fades, revealing a dull red.

Researchers from the University of Numar in Belgium used an electron microscope to take a close look at the beetle’s shell. They found that the shell has three tiers, or layers, arranged one on top of the other. The bottom tier is thickest. The top tier is thinnest. Each tier is made up of a number of closely packed smaller layers.

Each of the three tiers reflects light of a different color. Combined, these reflections produce a gold color. Beneath all three tiers is a layer of red pigment.

Within the layers that make up each tier, the scientists noticed tiny grooves. Sometimes, the beetle’s body fluids fill these grooves. When that happens, the layers become smooth. Then, they act as “perfect mirrors,” says Jean Pol Vigneron, one of the Belgian scientists studying the beetle. As a result, the bug looks shiny and metallic.

When the grooves are empty of fluid, on the other hand, the tiers act more like windows than mirrors. The shell loses its shine, and the red pigment shows through.

To make sure that the bug’s body liquid was essential to the color-changing process, the researchers froze a beetle in its gold state. Once it was frozen solid, the dead beetle turned red.

But when the scientists removed the beetle from the freezer, the bug’s frozen body fluid turned back to liquid and the beetle regained its gold hue. Later, when the insect dried out completely, it became red and stayed red.

This liquid-dependent process is “a new mechanism that hasn’t been found in nature before,” says Andrew Parker of the University of Oxford in England. He studies color changes in animals.

“Nature never stops surprising us with elegant solutions to everyday problems,” adds Radislav Potyrailo, an analytical chemist at the GE Global Research Center in Niskayuna, N.Y.

Scientists hope to some day apply the beetle’s technique to create devices that use color and light to show the presence or absence of liquids in other situations.