Cold house, hot house, green house

Saving energy at home requires paying attention to the building's windows, walls, and roof.

By Emily Sohn

When it’s cold outside, you turn on the heat. When it’s hot, you turn on the air conditioning. That’s about as much thought as most people ever give to temperature control at home.

You might want to dwell a little longer on the conditioned air that magically wafts out of household vents, however. The way you heat or cool your home has a big effect on the Earth, says John Carmody. He’s director of the Center for Sustainable Building Research at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

“Most people don’t usually think about where their heat comes from,” Carmody says. Yet nearly every type of energy source dumps waste or spews pollution into the air.

|

|

Heating and cooling the millions of buildings in the United States require a lot of energy and have a huge impact on the environment.

|

| South Florida Restoration Science Forum, U.S. Geological Survey |

Buildings have a huge impact on the environment. There are more than 81 million buildings in the United States, according to the U.S. Department of Energy. Buildings consume more energy than any other economic category, including transportation and industry. Almost half of the energy that buildings use goes into heating and cooling.

Like Carmody, a growing number of engineers, planners, and architects have been looking for new ways to make buildings less wasteful and kinder to the environment. Improvements have come in many forms, including better insulation, windows, and construction materials.

Architects are also realizing that the size, location, and positioning of a building affects how much energy it uses. Even the arrangement of buildings in a neighborhood makes a difference.

“In the last 10 years,” Carmody says, “there has been a major movement toward what you’d call ‘green’ buildings.” Such buildings are sometimes also described as sustainable, environmentally friendly, or healthy.

Temperature control

The amount of energy you use for heating and cooling depends on where you live.

In places such as San Diego, Calif., for instance, the temperature is mild all year round. People rarely have to regulate the temperature of their homes.

Where I live in Minnesota, on the other hand, winters are unbearably cold, and summers can be unbearably hot. Without heaters and air conditioners, we’d be in big trouble. (At least, I know I would be pretty miserable.)

|

|

Transmission lines carry electricity from power plants to communities.

|

| Oak Ridge National Laboratory |

To get a sense of your own environmental impact, you can look at the climate where you live. Ask yourself how often you turn on the heater or the air conditioner, and how high you pump them up.

You might also want to figure out the source of the energy that your house or school uses for temperature control. Most air conditioners run on electricity. Some heaters do, too. If you find a furnace in the basement and radiators around your house, though, that probably means you have a system that burns natural gas or oil to heat water.

These energy sources have their downsides. Electricity, for example, usually comes from power plants that burn coal or use nuclear fuel. Both produce dangerous waste.

And there’s energy lost along the way. “Only about a third of the energy generated at a power plant makes its way to a house,” Carmody says.

|

|

One alternative energy source is to use wind to generate electricity.

|

| U.S. Department of Energy |

As an alternative energy source, harnessing the power of the wind or sun is becoming more popular in some places. Windmills for generating electricity are springing up from California to Germany. And researchers are working to make solar cells, which absorb light from the sun and convert it into electricity, more efficient.

Sunlight can also be used to heat tanks of water. Still, the technology needs some work. For now, solar power is more expensive than traditional sources. And some places don’t have enough reliable sunshine or wind to make these approaches practical.

Windows, walls, and roofs

No matter where the energy comes from to heat or cool your home, simple design and construction choices can have a big effect on how much energy you end up using.

First, consider when your home was built. Old houses tend to be drafty, Carmody says. They lose energy to the outdoors.

Newer buildings have more insulation packed into the walls. Fluffy materials such as fiberglass and Styrofoam have lots of pockets for trapping air. Such a structure holds heat in, just like a cozy sleeping bag. Many environmentalists prefer cellulose fiber, which is made from recycled paper and wood, for insulation.

When it comes to energy efficiency, windows are a big issue. Instead of just looking through them, take a closer look at the windows where you live. If you can feel cold air rushing in even when the window is closed, that’s a good sign that you’re wasting a lot of energy.

|

|

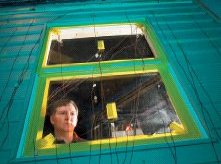

Researchers can monitor the energy efficiency of a wall and window combination.

|

| Oak Ridge National Laboratory |

New technologies are drastically improving window performance.

Windows used to be made from single sheets of glass. Today, windows are almost always double-glazed. This means there are two panes of glass set in a frame with an air space between them for insulation. Sometimes, windows are triple-glazed.

Scientists have also developed special coatings for windows. These invisible materials reflect heat. In a double-glazed window, coating the two sides of glass that face each other traps heat between the panes and increases insulation.

Chemists in England recently developed a kind of “smart” window coating. It reflects heat, but only when the window gets warmer than room temperature. If the technology becomes more affordable and practical, it could make windows even better at keeping the inside air in and the outside air out.

On the other side of the temperature fence, researchers from Oak Ridge and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratories are working on a new type of roofing material that they hope will cut the cost of air conditioning by 20 percent.

|

|

At Oak Ridge National Laboratory, researchers test “cool-color” roofing materials, which reflect more sunlight than typical shingles or tiles do.

|

| Oak Ridge National Laboratory |

If you’ve ever worn a black T-shirt on a sunny day, you know that dark colors absorb light and create heat. Most roofs are dark, so they absorb infrared and visible light, which makes a building warmer. The idea is to make shingles with colors that reflect certain wavelengths of sunlight. Such “cool” roofs should be available in 3 to 5 years, the scientists say.

Living spaces

Perhaps the most innovative strategy for increasing energy efficiency actually has nothing to do with technology. Instead, architects take advantage of the environment and landscape to control temperature inside a building.

In the northern hemisphere, this can mean installing lots of south-facing windows so that plenty of sunlight can pour in. At the same time, well-designed overhangs keep summer sun out but let winter sun in.

Some people are choosing to live in communities that have been specifically designed to promote energy-efficient living. Village Homes in Davis, Calif., was one of the first of such green, or sustainable, developments.

Completed in 1981, the neighborhood has a network of paths that encourages people to bike or walk instead of drive (and pollute). The development’s 240 houses face south for lots of exposure to the sun. Overhangs provide shade. Houses run on solar power. There are lots of trees. And narrow streets have as little pavement as possible.

The strategy seems to be working. The air temperature around Village Homes is 15 degrees F. cooler than surrounding areas that have more pavement. And residents spend between one-third and one-half as much on energy bills compared to more conventional homes in nearby neighborhoods.

“We have a shadier, cooler microclimate,” says developer and resident Judith Corbett, who spoke at an environmental design conference in Minneapolis last April. “I don’t even have an air conditioner.”

As people see communities such as Village Homes thrive, these types of developments are becoming more popular. They’re springing up in places such as Colorado, Arizona, Virginia, and Australia.

Zero energy

The U.S. government itself is taking steps to boost the energy efficiency of the nation’s buildings. In one project, the Department of Energy has a long-term goal to create a “net-zero-energy” house—a house that wastes no energy.

|

|

In Tennessee, builders are putting up a house that should produce about as much energy as it uses. The roof and walls are made from special insulated panels, and solar cells on the roof generate electricity for the home.

|

| Oak Ridge National Laboratory |

The Department of Energy’s development of “near-zero-energy” homes is one step in that direction. One such house in Tennessee runs completely on electricity for just 82 cents a day. Conventional homes in the same area use between $4 and $5 in electricity a day.

As research on efficient energy use continues, think about what you can do to live a more energy-efficient life in the meantime.

Keep the heat low or off when you’re not home. Make sure leaks around doors and windows get patched. Turn off lights, TVs, and computers when they’re not needed.

Better yet, if you’re cold, put on a sweater and have a hot drink. If you’re hot, consider having an ice cream cone or going for a swim.

ENERGY USE IN THE UNITED STATES (in quadrillion BTUs)

|

Year

|

FossilFuel

|

NuclearPower

|

RenewableEnergy

|

Total

|

|

1982

|

64.04

|

3.13

|

5.99

|

73.16

|

|

1992

|

73.52

|

6.48

|

5.91

|

85.91

|

|

2002

|

84.10

|

8.14

|

5.96

|

98.20

|

Btu, short for British Thermal Unit, is a unit of heat energy. One Btu is the amount of heat needed to raise the temperature of one pound of water 1° F. The heat given off by burning one wooden kitchen match is about 1 Btu.

Source: Energy Information Administration, U.S. Department of Energy